Tendons and ligaments that support the horse’s leg are stressed during both the push-off and landing when jumping. | ©Amy K. Dragoo

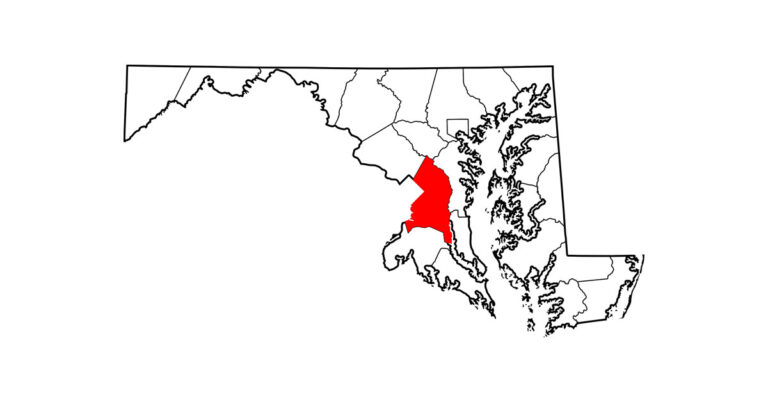

Tendons and ligaments that support the horse’s leg are stressed during both the push-off and landing when jumping. | ©Amy K. DragooIt’s midway through the season and your show calendar is packed. Maybe you’re hoping to qualify for equitation finals or collect points toward year-end awards in hunter or jumper divisions. Will you reach your goal or will an injury sideline your horse?

“Football players tear up their knees—it’s what they do. Hunters, jumpers and equitation horses are also athletes and they will get athletic injuries,” says Elizabeth Davidson, DVM, who focuses on equine sports medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s New Bolton Center. In this article, Dr. Davidson explains how some common injuries happen, how they’re treated and how they may affect your horse’s career.

Any horse can get hurt at any time, of course. But hunter, jumper and hunt-seat equitation competitions make demands that set horses up for certain injuries.

• Jumping stresses tendons and ligaments that support the leg during both push-off and landing. The impact of landing can also damage structures in the front feet. The bigger the jump, the bigger the stress.

• Speed increases the stress of jumping, so risks are higher for jumpers who are against the clock. Tight turns raise the odds of a misstep that could lead to injury.

• Repetitive stress takes a toll. Many horses in these sports show year-round–and when they’re not showing, they’re schooling. “With repetitive stress, minor damage can build up in ligaments or other structures,” Dr. Davidson says. “Then something tips it over the edge.”

What’s most likely to bench your horse? Hard statistics on injury rates in hunters, jumpers and equitation horses are limited, Dr. Davidson notes. “At any horse show you’ll see horses of different ages and breeds in different training programs and with riders at different skill levels. The variables make research difficult,” she says. Still, at a large referral clinic like New Bolton Center, many horses in these sports come in with problems in three areas.

Suspensory Ligament Tears

© Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy

© Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine AnatomyThe suspensory ligament acts like a sling, supporting the ankle joint as it sinks under weight and helping to return the joint to normal when the weight comes off. Tucked behind the cannon bone, this ligament starts just below the knee (or hock), splits into two branches that pass around the back of the ankle and ends on the front of the long pastern bone below.

What happens: If the strain is too great, the tough fibers that make up the ligament may tear. “This is an area that undergoes repetitive stress, so it’s a common site for athletic injury,” Dr. Davidson says. “In horses that jump, both front and hind injuries occur.” Although fibers can tear at any point on the ligament, proximal (high) injuries are common. The injury may be mild with just a few torn fibers, but in a severe case, the ligament may rupture or even fracture bone as it tears away.

What you see: “The horse may suddenly be lame, but usually damage has been building up as a result of recurring stress,” Dr. Davidson says. “Identifying the problem as early as possible, before severe injury, gives the horse the best chance of recovery.” Early detection isn’t easy with high suspensory injuries, though. A horse with a mild injury may be barely off and because the top of the ligament is hidden under other structures, you won’t find heat, swelling or sensitivity at the site.

What to do: Your veterinarian can find the problem with local nerve blocks and a hands-on exam. An ultrasound scan will show the exact site and the degree of injury to the ligament, and X-rays may show if bone is damaged. Magnetic resonance imaging can also identify damage to the ligament. “MRI is often helpful in hind-limb suspensory injuries, when ultrasound can be difficult to interpret,” Dr. Davidson says.

Every case is different, so your vet will help you work out a treatment plan that suits your horse’s injury. Treatment usually includes these steps:

• Cool down. To reduce inflammation, your vet may prescribe cold therapy (icing or cold-hosing several times a day) and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, such as phenylbutazone or Banamine® (flunixin meglumine).

• Stall rest to let healing begin. Your vet may advise standing wraps for the injured leg and the opposing leg.

• Hand-walking. Once inflammation is down, controlled walking encourages proper healing. Follow your vet’s advice, starting with as little as 10 minutes a day and gradually increasing the time.

• Gradual return to exercise. With your vet, set up a program that eases your horse back into work over several months, using ultrasound exams to monitor the ligament and adjust the program as needed.

Your vet may suggest other therapies, such as shockwave treatments. Stem cells or platelet-rich plasma can be injected at the injury site with the goal of improving healing. Research into these new regenerative therapies is ongoing.

Surgery—neurectomy of the deep branch of the lateral plantar nerve and fasciotomy—is an option for hind-limb proximal suspensory injuries that are reluctant to heal, Dr. Davidson says. In the hind limb, a band of connective tissue traps the top of the ligament in a sort of compartment and swelling within the compartment causes chronic pain. The surgeon cuts the connective tissue (fasciotomy) and the deep branch of the lateral plantar nerve (neurectomy), relieving pressure and pain. This nerve branch serves only the top of the suspensory, so the operation doesn’t otherwise affect the horse. Your veterinarian can help decide if your horse’s case is suited to the surgery.

What to expect: Ligaments heal slowly—anywhere from two to 12 months, depending on the location and extent of the damage. The process can’t be rushed. Re-injury is a risk even after healing because scar tissue that forms isn’t quite as strong as the original ligament tissue.

“Front proximal suspensory ligament injuries tend to heal well with treatment, but hind injuries often don’t respond so well,” Dr. Davidson says. “With conservative treatment only, less than 20 percent of horses with hind proximal suspensory ligament injuries return to previous levels. Surgery greatly improves the odds.” Keep in mind, though, that current rules bar horses from FEI competition after any neurectomy.

Sore Feet

© Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine Anatomy

© Illustrated Atlas of Clinical Equine AnatomyThe front feet take the brunt of landing after a jump and structures in the hoof capsule work together to handle the shock. The coffin joint—the meeting point of the small pastern bone, the navicular bone in the heel and the coffin bone in the toe—disperses the force. Ligaments that lash the joint together stretch then spring back. So does the deep digital flexor tendon, which runs behind the joint and helps support the navicular bone.

What happens: The feet are designed to handle great forces, but jumping fence after fence takes a toll. Common problems include:

• Strains and tears in the DDFT or the ligaments in the foot

• Inflammation in the coffin joint or in the navicular bursa, a fluid-filled sac that helps cushion the navicular bone from the pressure of the DDFT

• Deep bone bruising, which can appear in any of the foot bones

• Inflammation and degeneration of the navicular bone

“Sometimes there are multiple problems, Dr. Davidson says. “Again, these are injuries that occur through wear and tear—damage builds up until it hits the tipping point.”

What you see: “Because the injured structures are hidden by the hoof capsule, you don’t see swelling or other signs,” Dr. Davidson says. “Often these problems are bilateral, involving both front feet, so the horse may not be obviously lame. He may begin to move with shorter strides, but the gait is still symmetrical.” Or the horse may be lame and improve with rest, but be sore again when he goes back to work. He may rest a front foot or shift weight from one foot to the other when standing.

What to do: A lameness exam and diagnostic nerve blocks will help the vet determine the general site of soreness. Often it’s in the heel, or caudal, region, where several key structures come together. But to treat the problem, you need to know which structures are injured.

X-rays can reveal bone damage, but they won’t show soft-tissue injuries. Ultrasound is great for imaging soft tissues in the leg, but it’s hard to get a clear ultrasound image in the hoof capsule. The best tool, Dr. Davidson says, is MRI. “With MRI we are able to look inside the hoof capsule and sort out these problems much better than in the past,” she says. The results will help your veterinarian target treatment to fit the injury.

• A tendon or ligament injury needs a long period of rest, six months to a year. You’ll follow more or less the same program as you would with a suspensory injury with stall rest followed by a gradual return to work. The vet may recommend directed injections of platelet-rich plasma or stem cells.

• Inflammation in the coffin joint or the navicular bursa may respond to directed injections of corticosteroids, which are powerful anti-inflammatories, and hyaluronic acid, which is a natural component of cartilage and joint fluid.

• A bone bruise needs rest. This injury isn’t as serious as a fracture, but there is microscopic damage to the bone and fluid builds up within it. Healing can take three or four months depending on the degree of bruising.

• When the navicular bone is chronically inflamed, it responds by remodeling, losing mineral content in some areas and developing lumps of new growth in others. This pattern of inflammation and degeneration is often called navicular disease, and it doesn’t heal with rest.

What to expect: A horse with a mild injury has the best chance of recovery, but Dr. Davidson notes that rehabilitation can be challenging. “In sporthorses, significant pathology in the foot doesn’t have a good outlook. When the horse goes back to work, he stresses the same structures—so reinjury is likely,” she says.

Good trimming and shoeing are essential to keep the horse comfortable, regardless of what structures are involved. It’s important to keep the hoof trimmed at the correct angle, so the bones are properly aligned and the foot breaks over easily. Wedge pads or bar shoes can help take pressure off the heels. When problems persist, though, the horse may have to switch to a lighter work program.

Joint Problems

Careful trimming and shoeing are essential to keeping a horse comfortable and sound. The hoof must be trimmed at the correct angle in order for the bones to properly align and the foot to break over easily. Wedge pads or bar shoes may also help take pressure off the heels. | © Dusty Perin

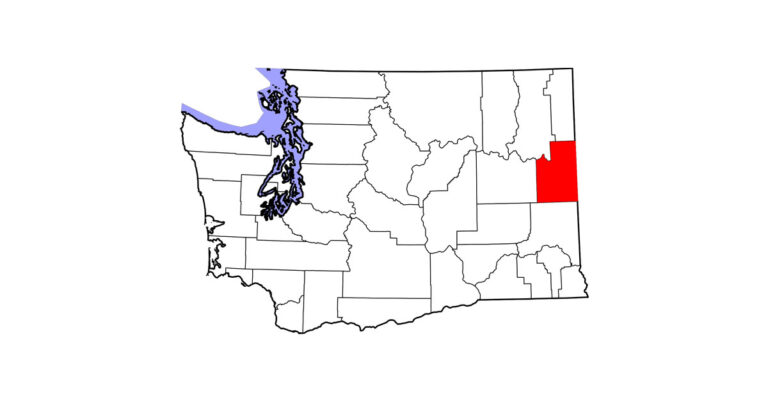

Careful trimming and shoeing are essential to keeping a horse comfortable and sound. The hoof must be trimmed at the correct angle in order for the bones to properly align and the foot to break over easily. Wedge pads or bar shoes may also help take pressure off the heels. | © Dusty PerinElite horses are especially prone to joint problems. Dr. Davidson says: “Jumping a lot of big jumps—and jumping every weekend—stresses joints and eventually triggers degenerative joint disease.” Common sites include the hocks and ankles, but DJD can develop in any joint that comes under stress when the horse works.

What happens: Chronic inflammation in the joint from injury or simple wear and tear sets off a destructive chain of events. The viscous fluid that fills the joint becomes thin and watery, so it doesn’t lubricate the cartilage that cushions the working surfaces so well. Under pressure, cartilage starts to wear away and the joint stiffens. There’s more concussion on the bones, which respond by remodeling. Lumps of new bone growth appear in the joint.

What you see: Joint problems often creep up gradually. At first your horse may be mildly sore or stiff or just seem less fluid or less forward, especially at the start of work. The soreness may improve with rest, but it returns. Over time it worsens and begins to affect his performance over jumps. You may find heat or swelling in the affected joint.

What to do: Your vet can perform a lameness exam and other tests to diagnose DJD. X-rays can show damage to bone and cartilage, but by the time this damage shows up the destructive process is well under way. Damage to the joint can’t be reversed, but you may be able to slow the progress of the disease by managing inflammation. Anti-inflammatory medications like phenylbutazone can help the horse weather a flare-up, but for long-term management there are other options.

• Injected directly into the joint, corticosteroids and hyaluronic acid help reduce inflammation and slow damage. The effects wear off in time and this treatment should be used judiciously. Repeated frequently, some corticosteroid injections have been linked to progressive joint deterioration.

• IRAP therapy is a new approach. The joint is injected with interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein, an anti-inflammatory substance derived from the horse’s own blood.

• Medications such as Legend® (HA) and Adequan® (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan, a component of cartilage) are another option. They’re injected systemically at intervals depending on the horse’s need. Response varies.

• Many feed supplements claim to protect joints from inflammation, but what little research exists is inconclusive. Unlike drugs, supplements don’t have to meet licensing standards or show that they’re effective; and no agency enforces quality standards. If these products help, they may be most useful in the early stages of inflammation. They aren’t likely to help a severe case.

• Adjusted work levels can help. Moderate exercise is good for joint health, but too much can trigger inflammation. Increase the horse’s turnout, give him longer warm-ups and let him be your guide in how much work you do. As long as he stays comfortable, you’re probably on the right track.

What to expect: DJD generally worsens over time, putting tighter limits on the horse’s career. Careful management can keep him going, but eventually he’ll need to switch to easier work.

Keep Him Sound

A daily hands-on leg check to look for heat, swelling or sensitivity can alert you to potential injuries. | © Frank Sorge/Arnd. nL

A daily hands-on leg check to look for heat, swelling or sensitivity can alert you to potential injuries. | © Frank Sorge/Arnd. nL“Injuries happen because of what these horses do,” Dr. Davidson says. You can’t eliminate the risk entirely and you can’t stop the clock when it comes to aging. “Most of us have one horse and we invest a lot of time, energy and money in that horse,” she says. “We ask horses to be athletes, but we forget sometimes that they can’t keep performing at the same level forever.”

Still, many factors that increase the risk of injuries are in your control. Take these steps to help your horse stay sound for many years to come:

• Don’t overtrain or overface him. Keep his work within his ability and be sure he’s in shape for what he’s asked to do. “Fitness—respiratory, cardiovascular, muscle, tendon, ligaments and bone fitness—helps avoid injuries,” Dr. Davidson says.

• Keep up with shoeing. Long toes and low heels put stress on the feet and on the joints, ligaments and tendons in the legs. Be sure feet are trimmed regularly so toes are kept short and use shoes with rolled toes to ease breakover if necessary.

• Use good sense on bad footing. If horses are sliding around in the ring, ask yourself: Is this class or this schooling session worth the risk?

• Stay alert for subtle trouble signs. Do a daily hands-on leg check, comparing opposite legs to detect heat, swelling or sensitivity. Watch for shortened strides and other markers of soreness. Give the horse a few days off if you suspect a problem. If the signs return when he goes back to work, ask the vet to check him out. A mild problem can blossom into a career-limiting condition if it’s ignored.

This article originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of Practical Horseman.

Save

Save