If you’re an eventer, you’ve long since noticed that—like the dressage—the show-jumping phase of your sport is increasingly important to your final result. A rail or two in stadium jumping can cost you your place on the leader board, even if your horse is a cross-country machine.

I love how Laine Ashker’s horse Rising Spirit is collected back over her hind end as she canters over a ground pole at a USEF High Performance Training Session I gave for eventers early last year in Aiken, South Carolina. The flatwork needed to be successful in show jumping is calmer and slower within the gaits than the more forward, animated dressage work needed for a successful dressage test. | © Hoof Pix Sport Horse Photography

That’s why top eventers on the U.S. Equestrian Federation training long list have been getting special “technical” coaching from show-jumping (and dressage) experts for several years. I coached elite U.S. eventers in 2010, when their goal was the World Equestrian Games, and in early 2011, and my take on what they need to do to improve applies to eventers at every level. Basically, I want my eventing students to approach show jumping with the same objective as the full-time show jumpers I teach: To be able to ride every line to perfection.

What do I mean by this? Although it’s not possible to boil down all the detail of my coaching methods into one article, I can talk about the major pieces of show-jumping that eventers typically need to focus on and why.

The Horses

Here’s where the challenge starts for eventers in show jumping: It’s very rare to find a horse who has the bravery and heart to do what is required of him in eventing’s cross-country phase and who has the careful aspect we look for in the show-jumping ring. Many of the horses who are good at cross country don’t mind brushing the jumps. They’re not bad jumpers; they’re just not “freaky careful” about not even touching a fence. In fact, the more experienced ones have learned that over certain cross-country fences, like brush jumps, they can actually “brush through” the top few inches of the obstacle. But when they get to stadium jumping, they can have a rail down with just a tick.

In addition, we show jumpers look for horses who jump a certain way—they snap up their knees in front and kick up their hind ends to clear the fences in back. A lot of good three-day horses have sort of an odd natural jumping style that needs to be molded into better show-jumping form. They have to learn to slow down, sit back on their tails and jump up rather than forward. I’ll talk later about the kinds of exercises I give eventing riders to create that form in their horses.

The Riders

The eventers with whom I work are all good riders. Unlike show jumping in the United States—where (as I’ve often said) I feel we are in danger of producing a generation of weak, protected riders—eventing in this country has lots of tough, seat-of-the-pants riders coming along with whatever horses they’ve been able to get. Those riders are fun to work with: hungry, hungry, hungry to learn and tough, which I love. They’re so courageous, so strong, and they can transmit that bravery to their horses to get the hard part, the cross country, done. But then, I think, they need to hone their skills in the other two phases. Their sport has become like the hunters and jumpers—an all-encompassing thing that goes 365 days a year, so that there’s no time to do anything except go to competitions.

In the old days, top eventers like Bruce Davidson would come and show with a jumper barn like ours for a month or so in the off season, and I know they would also go and work with dressage riders and compete in dressage with the pros for a month or two out of the year. Now they three-day-event every day of the year, instead of taking six months off to just go and show jump or just do dressage.

The challenge for U.S. eventers is that instead of being jacks-of-all-trades, they need to become experts of all trades, like Michael Jung, the young German eventer who won the individual gold medal at the 2010 World Equestrian Games. He is absolutely fabulous in every phase of eventing. He went to a jumping show in Stuttgart in 2010 and beat all the European show jumpers. I’ve heard he’s also won dressage classes against some of the top dressage riders in the world. If the U.S. three-day riders are going to beat riders like him, they have got to perfect their own skills in each phase. I’ll give you some examples of what we work on when they ride with me.

Position

I work on position with a lot of eventers. They are all strong riders in an active riding sort of way. On cross-country, they are off their horses’ backs in galloping positions and when they get to complicated jumping questions, they know how to drive their horses with their legs and seats to get over those huge, scary fences.

In show jumping, your horse still must be forward and in front of your leg, but you need to temper that. In addition to being forward, your horse needs to be as relaxed as possible so he can concentrate on jumping clean. Rather than sitting down in front of the fence and driving, you need to be still and controlled with your body in most instances on a show-jumping course. If you are flailing around, jumping ahead or pushing more than you need, your horse will probably respond by going forward, getting flat and touching the rail. In addition, most show-jumping fences aren’t impressive to event horses, so it’s your job to help your horse concentrate on how he’s jumping.

To help event riders learn how to be more still with their bodies when they jump stadium fences, I work on a lot of two-point exercises where they stay off their horses’ backs all the way to the fences, instead of dropping back to their seats and driving. We also do a lot of work on upper-body position: holding the shoulders up and staying quiet, rather than ducking down to push the horse forward. A light seat and still upper body encourage a horse to slow down his jump and jump the fence clean.

Flatwork

I’ve found that eventers have a different flat-riding background than we show jumpers have. The eventers’ beautiful, forward, animated dressage work and steady rhythm is what creates good dressage tests. The emphasis is on the quality of the movements and transitions. Their transitions, for example, need to be seamless. While the riders want the transitions to happen at specific points, it cannot be at the expense of how those transitions happen.

For a horse to show jump well, the flatwork is a little calmer and slower within the gaits than it is in dressage. But there is a heavy emphasis on how quickly he responds to what you’re asking, not on how expressive he is doing it. For example, on the flat, you want your horse to immediately gallop forward when you ask, then come right back when you ask. That way you can gallop around a course, then collect in three strides in a very controlled frame for the jump or line, gallop forward again, collect in three strides, it’s much quicker work between the speeds of the gait.

Conditioning for Show Jumping

I do a lot of work with gymnastics and ground lines to help the three-day horses (and riders) develop a better jumping style. A gymnastic that has a lot of ground lines and rampy oxers and slightly longer striding will help a horse who doesn’t have the sharpest front end. For a horse who is low and flat with his hind legs, I’ll set a line of two or three bounces about 10 feet apart with the ground lines rolled out a little past the standards so the distances between them are a little short. This encourages him to become quicker with his hind end (and can help the front end, too). The point of a gymnastic is to make the horse realize if he just tweaks his style this way or that, he’ll jump it clean and not have a rub or rail. The goal is to always try to help the horse jump better, not scare him.

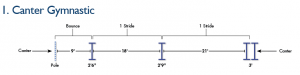

Diagram 1: Cantering from left to right, give with your hands and encourage with your leg as the distances between the fences and their heights increase. In the opposite direction, close your fingers and hold your shoulders up as the fences get smaller and the distances get tighter.

For a lot of these types of exercises, I’ll have the riders work over them at a collected canter, turning left or right after, cantering down the long side and repeating them three or four times, or circling and jumping them back in the other direction (see Diagram 1 at right). If a rider isn’t getting it quite right, I’ll say, “Loop back and do it again.” At that point, many of the three-day riders will say, “My horse is getting tired. This is too demanding!”

This always makes me laugh. My ?response is, “I thought your horses could run for four miles, yet you feel this type of work fatigues them.” From a training standpoint, it interests me that my jumpers probably couldn’t gallop four miles; however, they could do a collected canter up and down over little jumps for hours without overheating. The training that eventers do for the cross-country galloping is a science, but they also need to evolve conditioning for this type of collected work as well. It’s tedious but important?like mandatory figures in figure skating versus the freestyle.

Discipline

When I ask my eventing students to do a show-jumping course or repeat a line of jumps while adding or leaving out strides, they all say to me at first, “I can’t see a distance! I can’t see a distance!”

I say, “Yes, you can. You can see a distance. You all see distances beautifully. It’s the concentration and the discipline and the focus to see THE perfect distance to EVERY jump that you’re not used to.” Often it’s a matter of, “Don’t see THAT distance—see a different one!” Horses get more forward as they go around a stadium course, and often by the end, their strides become long and the distances the riders see become long and flat. Again, it’s your job as a rider to ensure that the control you have at the end of the course is the same as the control you had at the beginning of it.

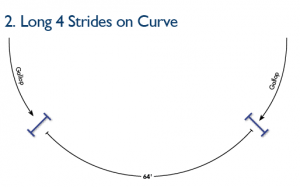

I have my eventers do the kinds of exercises we do all the time for show jumping. I set interesting gymnastics on a curve, for instance, lines where you have to come forward out of the turn to get the long four strides (64 feet) to the jump (see Diagram 2 at left). If your horse has an average-length stride, you can jump the line from center to center. If your horse has a shorter stride, you learn you need to jump the line from the center of the first jump toward the inside corner of the second jump. If your horse has a longer stride, you learn you need to jump from the center to the outside corner. It also shows you in which direction your horse drifts.

Diagram 2: To ride the line well, you need to come forward out of the turn to get the long four strides. If your horse has an average-length stride, jump it from center to center. If he has a shorter stride, jump it from the center of the first jump toward the inside corner of the second jump. If your horse has a longer stride, jump from the center to the outside corner.

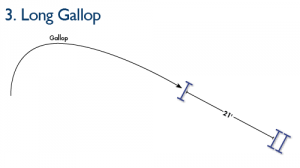

I might also have them ride a long gallop to an in-and-out in which the distance between the fences is short (21 feet for a one-stride): You have to gallop as you would around a corner to make the time on a stadium course, but then you must resist the urge to take the big distance in, which would make fitting in the one stride really difficult and cause a rail. Instead, four or five strides in front of the fence, you need to shorten your horse’s stride to be able to jump in slowly (see Diagram 3 at right).

Diagram 3: Gallop to this quiet in-and-out and within four or five strides of the first fence, smoothly collect your horse to be able to jump in slowly to fit in the one stride.

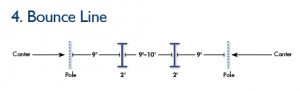

In my sessions with eventers last year, we worked on the horses’ style with a line of 2-foot-high bounces set 9-10 feet apart—usually two in a row—with ground lines and a placing pole either coming into the bounces or on the way out (see Diagram 4 below). I like this exercise because it helps the horse be quick with both his front and hind ends, but the ground lines keep him from getting too deep to the jump. As he improves, we gradually build the bounces higher (no more than 3 feet high).

Another favorite is to set two verticals in a line spaced four-and-a-half strides apart (66 feet) and have the rider ride it in both four and five strides: You flow in and leave out the stride, or come in quiet and add the stride. Then I set that line in a whole course where I say, “All right, you want to leave out the stride if this is the last line coming toward home; on the other hand, if you have a short turn right after this line, you want to make sure you add the stride.” This exercise reinforces your ability to do anything in the line you want to do, based on where it is in the course and what you need to do afterward. I love adding and leaving out strides, shortening and lengthening. It’s not just about controlling your horse but about your ability to make the right decision and then make it happen.

All of my lessons are geared toward exposing problems and weaknesses. When a horse makes a mistake in one of these exercises, I want the rider to understand what he has done wrong and figure out how to fix it. I’m showing different ways, different things to work on. Riders need to understand that the perfection of the ride is what enables horses to jump without touching the fences.

Diagram 4: I like to work on a horse’s jumping style with a line of 2-foot-high bounces. Each vertical has a ground line rolled out a little from its base. Bounces help your horse become quick with his front and hind ends, but the ground lines keep him from getting too deep.

It’s about understanding what your horse’s best jump is and how you create it, not once but all the way around the course. At competitions, this begins with the warm-up for the stadium phase: I want my eventers to really plan their warm-ups around what is perfect for that horse on that day. Do they need to jump a gymnastic that morning? Do they want to try to get a rub in the warm-up or not get a rub? Should they use a ground line or no ground line? I try to give them a different sort of hope and philosophy about the show-jumping part of their sport: With concentration and discipline, they CAN get good enough to influence the way their horses jump every fence.

I hope my biggest influence on the eventers I’m coaching will be to have them branch out and spend more time show jumping, not just within their own sport. I’d like them to bring their horses to the Winter Equestrian Festival in Wellington, Florida, and show in lots of classes. One show-jumping round as part of an event isn’t enough for eventers to get to know their horses: which lines are difficult or easy for them, what they spook at, how they react to different environments and types of footing. Eventers in the United States need to follow the example of world-class eventers I’ve known in Europe, like Mark Todd or ?Lucinda Prior-Palmer Green, who are good show jumpers in their own right.

Katie Monahan Prudent already had some experience coaching eventers when she started working with potential U.S. eventing team riders in 2010 (a position Olympic show jumper Lauren Hough has taken over). “I’ve been friends for years with Karen and David O’Connor, based not far away from my Plain Bay Farm in Middleburg, Virginia. I’ve also taught my very good friend Jan Byyny (whose Surefire Farm is in Purcellville), for whom I have great respect, and Alison Springer, one of the most promising younger eventers.”

Katie’s stellar career in the hunter/jumper world began as a Junior with wins in both the Medal and Maclay Finals followed by multiple championships in the hunter ring before she emerged as an international jumper star. A member of the 1986 gold-medal-winning World Championship show-jumping team, she has won almost every major grand prix in the United States and was named AGA U.S. Rider of the Year three times. She currently runs an international training program with her husband, French equestrian Henri Prudent. They divide their time between Middleburg and Rosires aux Salines, France.

The most recent of Katie’s many successful young jumper rider students is Reed Kessler, a member of the 2011 Young Rider Show Jumping Team that competed successfully on the European Young Rider Tour last year. The team won its first Nations Cup victory in Austria last June.

Still an active competitor herself, Katie plans to continue riding. “I’d like to stay good enough for the next few years to take a group of up-and-coming riders to Europe and compete with them.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2012 issue of Practical Horseman.