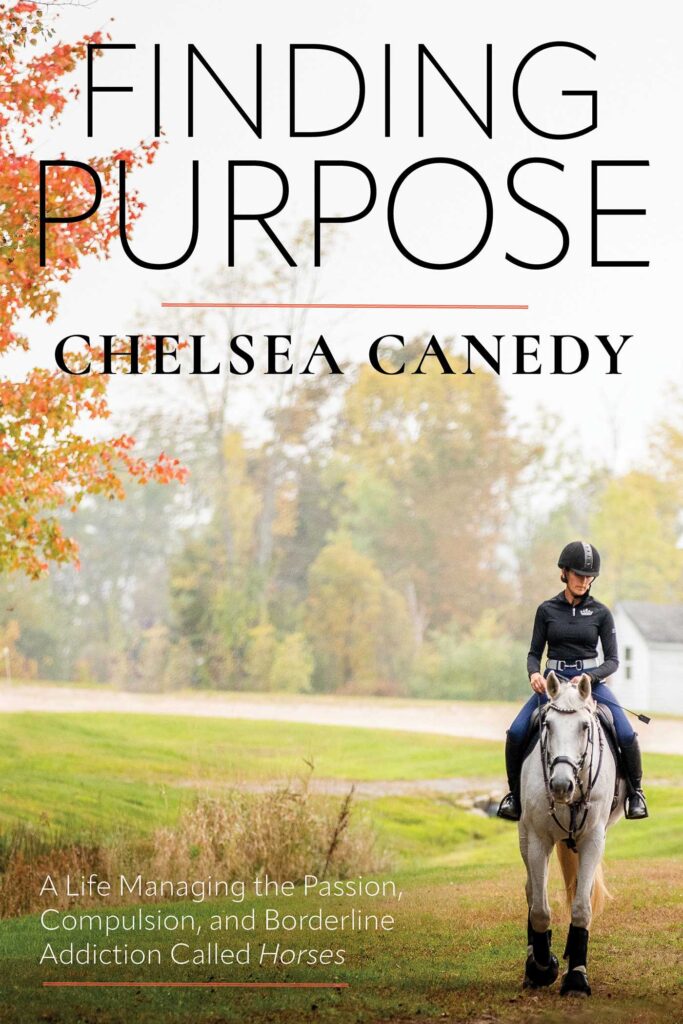

A few weeks ago, we shared the first excerpt of this two-part installment from eventer and Mustang advocate Chelsea Canedy’s debut memoir, Finding Purpose: A Life Managing the Passion, Compulsion, and Borderline Addiction Called “Horses.” From her early years in social service to her evolution as a respected rider, trainer and clinician, Canedy examines how her devotion to partnering with horses led to a philosophy of empathy, clarity and connection—on the ground, in the saddle and beyond the arena.

Here, you can read the second excerpt in this two-part installment from Canedy’s new memoir.

FINDING CLARITY

I reached out to Tik about getting some hands-on help upon our arrival in Florida. Luna was at the right stage in her understanding to be great practice for Tik as he prepared for competing at Road to the Horse, and I knew I would benefit immensely from his help with the next steps of her training. Tik also rode Lila twice, and I scheduled his trusted equine sports medicine veterinarian, Angie Yates, out to the farm to give the mare a once-over.

Tik could feel the issue I had been feeling. The way he described it was that he had to be extremely accurate to a jump for Lila to feel confident. When he made what he called a one or two percent change in his body or contact on the way to a jump, she said, “No thank you,” by leaving to the left of the fence. He also noticed as I had that if you got Lila more adrenalized by upping the energy of the work, you made it more likely that she would jump rather than run out, but in doing so, you also made it more difficult for her to keep her balance on the landing side of the obstacle.

This had a snowball effect when stringing several jumps together, as the landing side of one would become the unbalanced approach to the next, and so on, until Lila would become more flat in the air, and therefore, more likely to start dropping rails. Tik and I agreed that this was a tough ride to have as an eventer when show jumping was your least confident phase, like it was mine.

When the vet came to see Lila, she found her to be in excellent health. She flexed every joint in the mare’s limbs that she thought might cause discomfort when jumping and found nothing of note. She palpated her spine to no reaction, and outwardly could not see any reason why Lila might find it difficult to jump larger jumps. We talked about further diagnostic options and the benefits of following one path versus another. We talked about what the next steps might be if we found specific things, but it was all costly conjecture, as it so often is with horses. There was no clear, cut-and-dried answer, which made things even harder.

At least I could rest assured Lila was healthy and feeling good in her body. As horse owners, we are faced with a lot of choices during our lifetimes: Is it time to move up a level, or does my horse need more time where he is? Does my horse need to step down a level for his emotional or physical health? Should I move to a new barn for my or my horse’s well-being? Do I need a new instructor? Do I need to call the vet or get a second opinion about this mysterious lameness? And then there are the tough ones…like, Is my horse right for me? Should I sell him?

Any time I see a social media post scolding someone who has made the very hard decision to sell a horse, I feel immediately defensive of the person who had to make that decision. No one can know all the circumstances behind that choice—all the hours going back and forth, over and over the options and possible outcomes, the restless nights and guilt-ridden days, the curve balls that life may have thrown that made the decision for the individual. For anyone to simply assume that the decision to sell a horse is a selfish choice made without consideration of the horse’s well-being is inexplicable to me. Steve used to chide me when I would worry over a horse being sold to a new owner, asking me, “Who’s to say that the horse’s new owner won’t take better care of him than his last one?” He would rightly wonder why humans assume that they, and only they, can take care of a horse in the best way and that anyone else will surely do a lesser job.

I have thought of that often as I have taken in the many ways in which horses are cared for all over this world. I know how I think horses thrive best, and I also know there are people out there who would argue that their methods support horse health better than mine. Maybe we are both right…maybe the best rider match and daily routines that allow a horse to thrive can change over their lifetime. I know that to be true for the people who care for them.

These things were on my mind those first few weeks in Florida that season, as I wrestled with the decision of whether or not to sell Lila. After Tik’s assessment, it seemed more clear that the mare and I weren’t the best fit for each other in the show jumping phase of eventing. Thankfully, I knew with relative certainty that this was not due to any sort of medical issue, which ultimately, was great news. To me, it felt like the way Lila would need to be adrenalized and ridden to get the job done above Training level was not a way I felt confident or willing to ride, which was very hard to come to terms with. On some level, it felt like a personal failure. On a more rational level, I knew that it happens. Not every horse is a match for every rider, and it often takes time to figure that out. It’s not right or wrong, good or bad…it just is.

Once I came to terms with the situation, I began carefully weighing my options. I did not feel in a hurry, especially because I loved Lila’s personality and way of being so much. The way I saw it, I was back in a similar position to the one I had been a year before with Albert. I could keep Lila and pursue a dressage path, keep her and breed her, sell her as a lower-level event horse, or sell her as a dressage horse. After much soul-searching, I realized the bottom line for me was that I still was not done jumping, and I wanted to have a horse who willingly and confidently wanted to jump bigger things. It broke my heart that it wasn’t Lila because I loved her so much for so many reasons, and it just plain sucked that I didn’t have the money that would allow me to keep Lila just because I loved her, and also purchase my next eventing partner.

Thankfully, I knew that Lila was the kind of rare magical creature who would happily become the teacher that her next partner needed, and would inevitably settle into a new adventure with the grace and calm that she’d showed when she first came to me. Even with this understanding, I rode a rollercoaster of guilt, sadness, regret, second-guessing, and excitement for future possibilities.

I kept riding it as I began to advertise Lila while keeping her in work and enjoying our time together. I kept riding it as I showed Lila to several people and beamed with pride as she embodied all the characteristics I described her as possessing. I rode it as I witnessed a young girl fall in love with her in the first five minutes of their time together, and as I got an offer from her family to purchase the mare. I rode it as she passed her pre-purchase exam and the offer became a wire transfer to my bank account, making the whole thing real.

I gave myself permission to spend my last two days with Lila riding bridleless, hacking, and simply enjoying the best part of what the mare had brought to my life: a sense of ease and calm. I cried at the thought of losing that reliable daily stability, knowing the respite it provided in my busy and sometimes chaotic life. I cried at the thought of Lila’s confusion in being shipped off to a new farm with people and horses she didn’t know. I told her how much I loved her, as I hugged her neck and felt both our hearts beating. I kissed her floppy lips and felt her breath on my face as I explained what was changing between us and where her life was heading. I got the sense that she understood me in some way, as she rested her head against my chest, and we stayed there together for a long while. The tears choked off my words as I loaded Lila onto the trailer destined for her new home with her new people, and they continued as I walked to Luna’s paddock and cried into my Mustang’s shoulder.

Lila was a reliable ground to my often windy mind, and a reflection of my best self. Letting go of her meant letting go of that touchstone. It meant that I would no longer have her to help me remember to breathe and slow down every day. It meant that I was more on my own to do the work of being the thermostat for those around me, the way that Lila had been for me, and that felt both frightening and depressing.

Selling Lila was a heavier loss than I had expected, even though I knew it was the right choice for her and for me. It felt like she and I had come together at slightly the wrong time in both our lives. If she had been younger and at the middle of her career, or I had been older and ready to slow my competitive aspirations down, the stars would have been aligned for us…but they were just a little off, and the reality of that was painful.

Change is hard, and as my mother used to love to tell me growing up, it is the only constant in this world. Whether it is change resulting from choices we make or choices that are made for us, it is simply part of the human experience. I had a hard time going with the flow when I was younger, and having a sense of control was what kept my anxiety at bay. It wasn’t until I was an adult that I realized that my routines and need for structure, plans, and order in my life were my way of coping with anxiety. My habits and patterns were a set of learned coping skills that worked well for me, until life inevitably threw a wrench in the works and my best-laid plans had to change, like they did with Lila. In those moments, I would usually grasp at anything I could control and try to make a plan to get things back on track.

After years and years of laying those neural pathways in my brain, my default coping mechanism when I feel out of control is often still: make a plan, check things off lists, and regain control. Sometimes it works. Other times, not so much. Like when I have a horse that I thought would be one thing in my life and it turns out differently. I now see two options in cases like these: I can keep trying to shove a round peg into a square hole and beat myself up mercilessly for not being able to “make it work,” or I can get still, get quiet, and open myself to possibility, remembering that there is not right or wrong on the path of this life. I can either become defined by something I personally deem to be a failure, or I can see it as part of my journey, feel all the feelings and sensations that come along with it, and know that things will change again soon.

Sometimes, “feeling all the feelings” takes longer than expected, or we think we are done feeling them, and then something touches a raw nerve, and we realize we are not done. It’s easy to give others the heartfelt, empathetic advice to be gentle with yourself when traversing this kind of difficult terrain, but it is harder to follow the rule for yourself—or at least it is for me.

It is easy for me to look at the umbrella view of my privileged life, as someone who gets to play with horses for a living, has a beautiful farm, a loving husband, healthy children, and supportive family and friends, and to minimize my own feelings. I will often, uselessly, compare them to the larger problems of the world and its living beings, and feel guilty for ever complaining about anything. But those mental maneuvers don’t change my nervous system. They can’t talk my heart out of its heaviness or recalibrate my serotonin or dopamine levels. They usually only add to the confusion and guilt I am already feeling. So for me, I have to go back to the structure that provides me comfort, even though it doesn’t provide any concrete answers. I have to go back to my meditation practice and the community of people I have built around me who are also “doing the work,” and try to realign with the simple goodness of allowing everything to be, just as it is, even when it feels ugly.

Having Luna’s forward journey paralleling my struggles with Lila gave a sense of direction and purpose to my time in Florida that season, which would normally have been filled with competitions and lessons advancing my riding skills. Instead, I learned more about colt-starting than I ever thought I would. I got to follow more of Amy Skinner’s advice: “The sooner you can develop the ability to differentiate criticism about something you are doing from your self value, the sooner you can learn and learn well.”

While no one had blatantly criticized me for the work I had done with Luna, there was more than enough self-criticism along the way. But every day that I watched Tik work with Luna, I had the opportunity to recognize those critical voices for what they were—immaterial roadblocks to my own development. I got to consciously practice allowing them to dissolve back into the space they arose from and let them float away on the Florida breeze while I refocused on the daily journey of learning. I got to watch Tik prepare for Road to the Horse at several clinics with people considered to be horse training masters, which meant I was adding more tools to my theoretical toolbox. Some clinicians showed me what to do, and others showed me what I would not ever do.

I realized that my tendency toward softness and fluidity that allowed me to work with very sensitive horses did not always offer me or them the opportunity to see what we would do when things got loud or messy. In my efforts to help Luna feel comfortable and at ease with the work she did with me, I hadn’t exposed her to enough chaos or taught her about recovering from it gracefully. We had dipped our toes in, but we hadn’t explored those depths to know how we would handle them together. I watched Tik press into those areas with my Mustang and help her come out on the other side, realizing that she was okay and that the human could still be trusted. She learned that sound and movement above and behind her were not a threat that meant she should flee the scene, which went completely against her base instincts.

My first couple of rides back on Luna definitely triggered a stress reaction in me, even though logically I knew she was in a more stable place. We were in a round pen, I was in a Western saddle and a rope halter, and Luna had been demonstrating a tolerance for being ridden that I had been able to watch and absorb. We had been working on bringing the energy up around her and then bringing it back down from the ground together, and her reactions were very consistent, trending in a predictable direction. But my heart still raced and my legs still felt a little like jelly when we started walking around the pen with me on her back, and especially when we took a few trot steps.

My mind showed me images of the whole thing unraveling and me being thrown into a round pen panel as Luna spun quickly in the opposite direction and took off. I had to purposely take deep slow breaths to recenter and bring myself back to what was actually happening under me: Luna walking calmly around the inside of the pen. I also gave myself absolute permission to get off her if I felt she was building up to something, as I knew I would be no use to her learning process if she exploded again.

I let Tik take on many of her firsts over the following weeks: Her first canter under saddle, her first ride out of the round pen, her first trot poles with someone on board. Psychologically, seeing her do each new thing without incident gave me the confidence to try them with her. And just like everything else I had done with Luna, once she got something, she had it. I kept reinforcing her understanding with the clicker and treats, and the positive reinforcement clearly helped her understand new ideas and sensations more quickly. Within a few weeks, we were venturing out of the round pen, walking, trotting, and cantering in open spaces, and even hopping over some small jumps. We took field trips to Copperline Farm for lessons, and to cross-country schooling spaces to play with water, ditches, and small jumps with me handling her from the ground. Luna was unfazed, even bold about these new obstacles.

We stepped into a dressage arena without fear of the judge’s booth or the sound of sand on the low panels at her feet. We walked into new barns and met new people without shying away. Luna had her feet trimmed for the first time, and then a second and third time. She had her teeth floated and her wolf teeth removed. She allowed me to clip her neck and shoulders without sedation, and she learned to get on and off a trailer like an old pro. We went to horse shows where I was coaching others and hung out on the edge of the warm-up arenas, taking in the atmosphere without worry.

It was all really impressive, honestly, considering where Luna and I had been just a few months prior. I wanted to hang a sign around her neck to tell the world her story. I wanted people to know that she was a Mustang, and that everything I was doing with her was her first time doing it. I wanted people to understand why I was so excited that she hopped over a tiny jump in a new arena or walked calmly into a huge open field full of jumps and galloping horses. I felt so proud of her and how far we had come together, and I wanted others to share in the wonder of her progress. I also recognized a part of me that wanted to explain why I was riding a slightly downhill pony instead of a lovely, eye-catching, competition horse like Lila.

That small part of me wondered what people thought of Luna, and if they assumed I was an amateur rather than a professional. That part of me stole some of the genuine joy the rest of me felt about Luna’s progress, and I didn’t like it. I tried not to fight it, as Marcy had coached me to, and to just observe it, and bring my focus back to the authenticity of my time with Luna. I tried to remember to thank that tenacious, competitive part of me for all she had done in my life—and then let her know that I wasn’t in need of her services.

NOTE: Reprinted from Finding Purpose: A Life Managing the Passion, Compulsion, and Borderline Addiction Called “Horses” by Chelsea Canedy by permission of Trafalgar Square Books

For More:

- You can purchase a copy of Chelsea Canedy’s new memoir here.

- To read the first except from her book on Practical Horseman, click here.

About Chelsea Canedy

Chelsea Canedy stands apart as a competitive rider who combines traditional training with natural horsemanship, groundwork, liberty work, and R+ methods. Her background in social service and psychology informs her unique approach, blending mindfulness and communication with equine training. She has appeared on leading equestrian podcasts and is a frequent clinician and presenter at festivals and expos nationwide.

Chelsea and her family live in Wales, Maine, where they run Unexpected Farm, a historic property devoted to horses and community. She also winters in Ocala, Florida. Learn more here.