Ah, spring—time for the annual quandary over which shots to give your horse. You can vaccinate against everything from anthrax to snakebite, but that doesn’t mean you should. More isn’t necessarily better when it comes to vaccinations.

“It’s important to balance the risk of disease against the risk of overstimulating the immune system and triggering side effects,” says Elizabeth Davis, DVM, professor and section head of equine medicine and surgery at Kansas State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. In this article she helps explain how to find that balance and how vaccination guidelines from the American Association of Equine Practitioners, online at aaep.org, can simplify the task.

Vaccines reduce but can’t always eliminate disease, Dr. Davis notes. Use them as a tool along with good management and bio-security practices that limit the risk of infection. Your most important resource is your regular veterinarian. “You may be vaccinating your horse yourself, but you should still get your veterinarian’s input on the ideal protocol,” she says.

Have a Plan

Your horse needs the right vaccinations at the right time to be protected from disease. Vaccines work by priming the immune system against specific viruses, bacteria and other disease-causing organisms. Some are made from killed or inactivated organisms (or products derived from them) along with adjuvants that help stimulate the immune system. Others contain living but weakened versions of the organisms, potent enough to trigger an immune response without causing disease. A few combine proteins from the pathogen with live but harmless canarypox virus, which helps prime the immune system.

The horse’s body recognizes vaccine agents as foreign antigens and responds. White blood cells that can identify the specific antigen multiply rapidly. Some, called B cells, produce antibodies that circulate in blood and neutralize that antigen. Others, T cells, destroy infected body cells and help orchestrate the response. If the real disease-causing agent shows up later, the horse can mount a faster and more powerful defense. “White blood cells and antibodies targeted to that pathogen are ready and waiting for it with a pronounced memory response,” Dr. Davis says.

The immune system needs time to respond to vaccines and build up these defenses, so as a rule you should give a vaccine approximately two weeks before you expect your horse will encounter the risk. If he has never been vaccinated against the disease, establishing a protective level of immunity will require a series of shots spaced several weeks apart (depending on the vaccine). In this case you’ll need to schedule the initial vaccine even farther in advance of exposure. After that, the horse will need boosters annually or more often, depending on the vaccine and the risk of exposure to the disease.

The same process that builds immunity can also produce side effects. Vaccines are tested for safety, but mild reactions, such as fever and local muscle soreness, are common. Less often, an intramuscular injection leads to a bacterial infection. In rare cases, vaccines have caused severe allergic reactions—so avoiding unnecessary vaccination is important.

To tailor your horse’s vaccination program to his situation, consider

- Location: The horse should be vaccinated against diseases he’s likely to encounter where he lives or may be shipped. Some risks are widespread, some regional and some local.

- Lifestyle: Horses that go to shows or other venues where they encounter horses from other barns need protection against diseases that spread horse to horse. Where other horses could bring infection onto the farm, even horses that stay home need protection. Horses can carry some diseases without showing symptoms, shedding bacteria and viruses, and infecting others.

- Use: Broodmares may need protection against diseases that can cause abortion. Revaccinating mares four to six weeks before foaling helps ensure high levels of antibodies in colostrum (first milk), which help protect foals in the first months of life.

- Age: Young horses (under age 5) are more susceptible to some diseases, such as equine herpesvirus and West Nile virus.

You might hope that an aged horse would build up immunity over the years and wouldn’t need many vaccinations. But there’s little evidence of that. “A 29-year-old horse at pasture may have less exposure to certain diseases, so he may need those vaccinations less often,” Dr. Davis says. But like people, whose immune response weakens with age, horses also show changes in their immune response as they grow older, she notes. “Although we don’t have evidence that older horses get sick more often than younger horses, we do know that it’s important to maintain proper vaccinations for this population. And many older horses develop equine Cushing’s disease, which suppresses the immune system. It’s important to treat them for that condition as well as keep their vaccinations up to date.”

The best course is to review your horse’s vaccination program with your vet annually to ensure it fits his current needs.

Core Vaccinations

The AAEP designates certain vaccinations as “core,” recommended for practically all horses in the United States. They are

Tetanus: Tetanus bacteria are everywhere, including the soil, where they form spores and become dormant. If they find their way into a penetrating wound, they germinate and begin to produce a potent neurotoxin. Horses are highly susceptible to the toxin, which causes violent muscle spasms and potentially fatal complications.

- Vaccination with tetanus toxoid (a weakened form of the toxin) gives safe and reliable protection.

- Vaccinated horses need an annual booster, which can be given at any time of year. If the horse gets a wound and it has been more than six months since his last booster, he should have another.

Rabies: A virus that attacks the nervous system causes rabies. It occurs in every state except Hawaii, mainly among wild animals (especially skunks, raccoons, foxes, coyotes and bats). Although it’s not common in horses, there are equine cases every year. A rabid animal wanders out of the woods and bites a horse, or the horse has a wound that becomes contaminated with saliva or blood from a rabid animal.

- Rabies is always fatal and poses risks to anyone in contact with an infected horse, but vaccination provides reliable protection.

- An annual booster can be given at any time of year. “In most states rabies vaccinations must be performed by a licensed veterinarian,” Dr. Davis says. “If you administer other vaccines yourself, consider having rabies administered when you schedule another veterinary procedure for your horse rather than as a separate farm call.”

Eastern equine encephalitis/Western equine encephalitis: Biting mosquitoes spread viruses that cause EEE and WEE. The viruses attack the horse’s nervous system, and EEE is the deadlier of the two—only about 10 percent of clinically affected horses survive. It occurs mainly in the eastern, Gulf Coast and midwestern states; WEE, which is less common, occurs mainly in the west. (Venezuelan equine encephalitis, a related virus, hasn’t been reported in the United States for more than 35 years. You don’t need to vaccinate against it unless your horse will travel to an area where the disease has been reported.)

- Vaccines for EEE and WEE are usually combined in a single shot, often with tetanus and other vaccines.

- Boosters should be given in spring so the horse can build immunity before mosquito populations peak in summer. “Hot, wet summers increase the risk for mosquito-borne diseases,” Dr. Davis notes.

- In areas where mosquitoes are active year-round and the risk is high, horses may need a second booster in the fall.

West Nile virus: Although WNV belongs to a different viral family than EEE, it also spreads via mosquitoes and attacks the horse’s nervous system. It first appeared in North America 15 years ago and has since spread throughout the continental United States and into Canada and Mexico. About a third of horses who develop clinical signs of WNV infection die, and survivors may have long-term gait and behavior problems.

- There are currently four licensed WNV vaccines based on different technologies, but all are safe and effective. Your vet can advise you on which is best for your horse.

- As with EEE/WEE, boosters should be given in spring to build immunity before mosquito season and repeated where the risk is year-round. This is especially important for young horses and older horses with Cushing’s disease, who are more susceptible to WNV.

- “If you import a horse, be aware that vaccination for these mosquito-borne diseases isn’t routine in Europe and the horse may have no protection against them. Find out the horse’s vaccination history, and get the initial series before he comes, so he’s protected on arrival,” Dr. Davis says.

Respiratory Risks

The AAEP lists other vaccinations as “risk-based”—the need depends on your horse’s situation and specific disease risks. Among the top risks are three respiratory diseases that spread horse to horse.

Flu: Equine influenza, which is caused by a virus, is among the most common infectious respiratory diseases in horses. The AAEP recommends this vaccination for all horses except those who live in a closed, isolated herd—they never leave the farm and have no contact with outside horses. For the rest, risk levels determine how often to administer a booster.

- Horses who show often or live in barns where horses are in and out should get a booster every six months.

- Horses who are only occasionally in contact with others can get along with an annual booster. Time it to maximize immunity when risk of exposure is highest.

There are three types of flu vaccines—inactivated, modified live virus (intranasal) and canarypox vector—all safe and effective. In unvaccinated horses the intranasal provides the quickest response.

Equine herpesvirus: Equine herpesvirus type 1 and equine herpesvirus type 4 usually cause a flu-like illness (rhinopneumonitis) with fever and respiratory symptoms. EHV-1 can cause pregnant mares to abort, and in some cases the virus damages blood vessels in the brain and spinal cord, producing equine herpesvirus myeloencephalopathy, a neurologic disease that can be fatal. In recent years veterinarians have identified a strain of the EHV-1 virus that has caused serious outbreaks of EHM.

- Many horses are infected with EHV early in life as weanlings and carry the virus for life. Like other herpes viruses EHV goes latent, hiding in the body. When the horse is stressed—by shipping, fatigue or some other cause—the virus may become active. Carrier horses may not show signs of illness, but they can shed the virus and spread it to others. Vaccination helps prevent respiratory illness and reduce viral shedding.

- Some vaccines also help prevent EHV-caused abortion and are labeled for that.

- There are no vaccines labeled effective against EHM. Some studies suggest that a modified live virus vaccine (Rhinomune MLV from Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica) or a high antigen-load killed vaccine labeled for preventing abortion (Pneumabort K from Zoetis) may lessen the severity of the neurologic disease, but more research is needed.

“For a horse at high risk, I would boost with one of these. There is no evidence that vaccines labeled only for preventing respiratory EHV will protect against EHM,” says Dr. Davis.

- Annual boosters are appropriate for most horses, but those at high risk—performance and show horses, horses under 5 years old and those on breeding farms or in contact with pregnant mares—may need boosters every six months.

Strangles: Strangles, caused by Streptococcus equi bacteria, is common and highly contagious. Early signs include fever, depression and cough, followed by swelling of the lymph nodes around the horse’s jaw and throatlatch. Soon a discharge of pus begins draining from the horse’s nose. Abscesses may form in the lymph nodes and burst open to drain. Occasionally the bacteria spread to lymph nodes elsewhere in the body and there can be serious complications. Young horses are often hardest hit.

Both killed injectable and modified live intranasal vaccines are available, and they can help prevent or reduce the severity of the disease. The AAEP recommends vaccination on farms where there is a history of outbreaks and for horses that are at high risk of exposure.

- “Strangles vaccines produce a strong response, and there is more risk of side effects than some other vaccines,” Dr. Davis says. “A horse that’s at low risk can probably skip this vaccination. This would be a horse that mainly stays on a farm, in a closed herd where the health status is known for all the horses and new arrivals are quarantined for two weeks. Even if the horse leaves the farm a few times a year, strangles vaccination may not be necessary because the risk of exposure is low.”

- For horses at high risk, such as those going to shows where many horses mingle and you’re not sure of biosecurity, vaccination may make sense. To lower the risk of side effects, Dr. Davis advises having your vet run a blood test to check your horse’s level of antibodies. Vaccinate only if the titer is below 1:1600.

Less-Common Risks

Talk with your veterinarian to assess your horse’s need for these vaccinations:

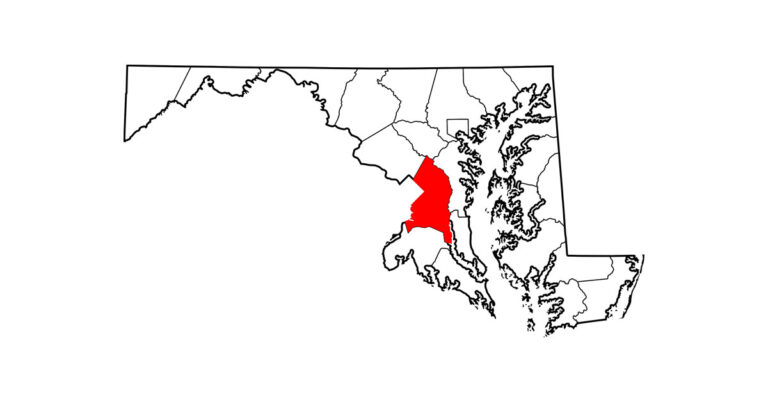

Potomac horse fever: If there have been cases of Potomac horse fever (equine monocytic ehrlichiosis) on your farm or nearby, your vet may recommend vaccination. This disease occurs in many areas of the country, but risk is local. It’s caused by a bacterial organism with a complicated life cycle, moving through parasitic flukes, water snails and insects. Horses are thought to pick up the bacteria by eating insects that die and fall into hay or pasture. These insects emerge in warm weather, so vaccinate in spring.

Equine viral arteritis: This respiratory disease is contagious but so mild that most horses don’t need vaccination. But the virus that causes it also causes abortion in pregnant mares. Broodmares can be vaccinated before breeding. So can stallions, who can carry and spread the virus without showing signs. Some countries bar stallions or mares if tests show antibodies to the virus. It’s impossible to tell whether vaccination or the disease triggered the antibodies, so the AAEP recommends documenting disease-free status by testing for antibodies before vaccinating against EVA for the first time.

Rotaviral diarrhea: Rotavirus is a major cause of foal diarrhea. Vaccinating pregnant mares helps protect their foals. Other horses don’t need this shot, and no evidence shows that vaccinating newborn foals has benefits.

Botulism: Broodmares can be vaccinated against the form of botulism that causes shaker foal syndrome. The vaccine protects their foals from this usually fatal condition, but it doesn’t protect horses from other forms of botulism.

Anthrax: Few horses need vaccination against anthrax; the bacteria that cause this deadly disease are found in scattered sites mainly in the Southwest.

Snakebite: A new vaccine promises to protect horses from the toxin delivered by western diamondback rattlesnakes, something to consider if you’re in snake country.