I am lucky: I live surrounded by history. From my office window, I can see the John S. Mosby Highway, named for the legendary Confederate commander of Mosby’s Raiders during the Civil War. Washington commuters drive that road to and from work in downtown D.C. This is the same road that, as a young man, George Washington used to ride over the Blue Ridge on his way to survey the Western Territories for Lord Fairfax.

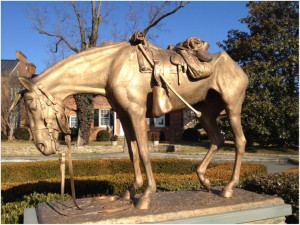

The monument in front of the National Sporting Library and Museum depicts in heartbreaking fashion the result of horses being pressed beyond their capabilities. Note the gaunt condition of this horse. The empty sword scabbard signifies that his rider has fallen in combat. Over 1,500,000 horses and mules died in the Civil War.

The monument in front of the National Sporting Library and Museum depicts in heartbreaking fashion the result of horses being pressed beyond their capabilities. Note the gaunt condition of this horse. The empty sword scabbard signifies that his rider has fallen in combat. Over 1,500,000 horses and mules died in the Civil War.The gravel lane next to my farm is the same road Confederate troopers galloped down on their way to confront the Union cavalry just east of Upperville, Virginia. The Battle of Upperville was partly fought over the grounds of today’s Upperville Horse Show, which lie along Mosby Highway, modern-day U.S. Route 50. The remains of many of the men who fell that day, June 21, 1863, lie in local cemeteries, and there are gravestones and monuments to mark their passing. But the bodies of the horses and mules that died alongside their masters were dragged into a field on my neighbor’s farm and left behind. The only monument they received was the rock and rubble used to cover them.

From 1912 until 1948, U.S. horses and cavalrymen represented our country in the Olympic Games. This month, I’ve dedicated my column to remembering cavalry horses throughout the ages and from different nations, who instead of carrying us over cross-country courses, down centerline or around the stadium arena, bravely carried their riders into battle.

Always There, Always Eating

In my readings and studies of the wars that swept across the Virginia countryside and, indeed, around the world, I am continually struck by the presence of horses. The horse has been a conveyance, a partner and, unfortunately, occasionally a source of sustenance throughout mankind’s long record of armed conflict.

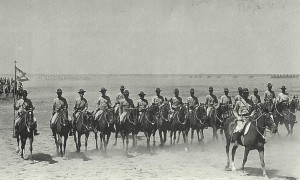

What an evocative photo this is: The past and the future captured in the same image. Brig. Gen. Jonathan M. “Skinny” Wainwright is shown leading the 5th U.S. Cavalry Division in its final mounted parade, May 1939. The horse he is riding might be Joseph Conrad, his favorite charger. His troopers are correctly equipped for mounted warfare. However, in the background you can see motorized transports, harbingers of the changes that were coming to modern warfare.

What an evocative photo this is: The past and the future captured in the same image. Brig. Gen. Jonathan M. “Skinny” Wainwright is shown leading the 5th U.S. Cavalry Division in its final mounted parade, May 1939. The horse he is riding might be Joseph Conrad, his favorite charger. His troopers are correctly equipped for mounted warfare. However, in the background you can see motorized transports, harbingers of the changes that were coming to modern warfare. One of the many interesting things about our association with horses is the effect it has had on other aspects of society. For example, horses in hard service need cereal grains to produce enough energy to continue working. Grazing alone will cause them to fall into a much-reduced condition. When horses were still used in warfare, the entire countryside would have to devote much of its arable acreage to raising the corn and oats needed to sustain horses in their labors.

In wartime, this was a challenge at best. There were about 10,000 horses present on each side at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, and cavalry commanders faced enormous logistical problems in caring for their mounts. For example, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s cavalry at Gettysburg needed 90 tons of hay and 170 tons of corn every day! And, of course, they needed water, 450,000 gallons daily. For a rough estimate of how much water that is, look at a medium-sized tanker truck the next time you are on an interstate highway. That tanker probably holds about 4,000 gallons and is about 25 feet long. It would have taken a convoy of more than 40 such trucks, stretching “head to tail” for about a quarter of a mile every day to supply Lee’s horses with enough water. Obviously, such mechanized support was unavailable at the time, and dehydration was a severe problem.

To understand just how much 170 tons of corn is, imagine a row of 20 stalls. The corn would fill all 20 of those stalls approximately to the top. This amount was the guideline, but the officers were often unable to provide for their horses, and the horses suffered accordingly.

From 19th to 20th Century Warfare

During the Civil War, the U.S. Army issued 2,500 wagons and 35,000 horses and mules for every 100,000 men in uniform. Given that by April 1865, President Abraham Lincoln had nearly one million men in the armed services, the hay-, grain- and water-supply problems were staggering. Another way to picture it: At the close of the Civil War, the Union staged a Grand Review in Washington, D.C., with the U.S. Army marching past the White House on May 23-24, 1865, in final salute to President Andrew Johnson (President Lincoln had recently been assassinated). There were so many mounted troopers that, riding 12 abreast, they made a column seven miles long and took well over an hour to pass.

These thousands of riders passed by without incident except for a 26-year-old Major General of Volunteers named George A. Custer, who caused quite a stir. Someone in the throng gathered along the route threw a wreath to Custer?the closest thing to a rock star the 1860s could produce causing his horse to spook and bolt and leave a trail of confusion in his wake. He passed by the White House so quickly that Gen. William Sherman remarked in amusement that he “was not reviewed at all.” (Getting run away with during an important parade was a fairly good means of promotion for young officers, as you shall soon see in an upcoming story.)

The numbers of horses used in war in other eras are also staggering. When people wonder today at the fact that a show or event might have several hundred horses on the grounds, I am reminded that when World War II broke out in 1939, the United States had 12 million horses and 4.5 million mules.

Similarly, for all its vaunted “Blitzkrieg” (“lightning war”), which relied heavily on tanks, planes and artillery, the German army was surprisingly horse-drawn at the outbreak of World War II. If Hitler had decided on an invasion of England in 1940, he would have had to ship 125,000 horses across the English Channel to provide his army with transport.

The U.S. still had cavalry troops in action in the Philippines in 1941-42. The commanding general of the 26th U.S. Cavalry Regiment was a tall, tough, polo-playing, whisky-drinking cavalryman, Gen. Jonathan M. “Skinny” Wainwright. A good commander never orders troops to do anything he would not do himself, and Wainwright was a good commander. Forced to retreat, he ordered the destruction of the remaining horses to deny their use to the Japanese. However he could not bring himself to shoot his own charger, Joseph Conrad. To spare Wainwright, his officers quietly arranged for Joseph Conrad and the other remaining horses to be destroyed.

Wainwright was forced to surrender the Philippines and the 26,000 men under his command, April 9, 1942. He survived the Bataan Death March, and upon his release from the POW camp was promoted to four-star rank and awarded the Medal of Honor. He was never the same man, however, and he died shortly after his retirement. It was said that the cause of death was whiskey, but those who knew him said he died of a broken heart, thinking of the men and horses he had lost. (The horses we are talking about were not the only casualties of war.)

Earlier in that conflict, the 26th U.S. Cavalry resorted to eating horseflesh to survive, but it wasn’t the only military unit through the ages to do so. When Napoleon began his disastrous retreat from Moscow in the fall and winter of 1812, his cavalry was forced to eat its horses. In the winter of 1941-42, the German army retreated from Moscow under similarly disastrous circumstances, and those men also ate their horses to survive.

Horses suffered in other ways, too. The few descriptions of the effect of weapons on horses make chilling and depressing reading; I do not recommend it. Whether it was by an arrow at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, by the cannons mentioned in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s grim poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” in 1854 or by artillery fire in World War II, the horses suffered and died. We still have much to do in the improvement of horse care, but we can at least take small comfort that we no longer ask them to charge barbed wire and machine guns.

Lighter Moments: A Mule Charge

These are sad and serious considerations, and we must alleviate them by observing that any time a large number of men, mules and horses are gathered together, some unintended and comic things will occur. At the Battle of Chattanooga on October 29, 1863, the Confederate forces attempted a night attack. This was a highly unusual tactic during the Civil War due to the obvious difficulty of maintaining command and control before the invention of radio. But desperate times call for desperate measures. Under Gen. Micah Jenkins, the Confederate forces had some initial success with this plan, however, at the climactic moment, 200 Union mules broke loose from their picket lines and stampeded through the attacking Confederate forces in pitch darkness, kicking, squalling, braying and knocking over tents, wagons and men with equal abandon. Convinced that Gen. Grant’s U.S. Cavalry was breaking through their ranks, the Confederates broke for the rear. Contemporary diaries affirm that the rout was complete, as military order and discipline were laid aside in the interest of speed and efficiency. The next morning, Grant jokingly mentioned that he should promote the mules for gallantry in action.

For centuries, horses have carried their riders through horrific conditions. Here, the horses of the 5th Army Provisional Mounted Reconnaissance Troop walk calmly amid the devastation in Italy during World War II.

For centuries, horses have carried their riders through horrific conditions. Here, the horses of the 5th Army Provisional Mounted Reconnaissance Troop walk calmly amid the devastation in Italy during World War II.President Lincoln showed he had a healthy appreciation of the relative value of his generals and his horses. On March 9, 1863, Mosby captured U.S. Gen. Stoughton and a large number of horses in a daring raid into Fairfax, Virginia. Learning of this, Lincoln remarked, “Well, I am sorry to hear about that. I don’t care about the general so much. I can make another in five minutes.” He paused for a moment and then added, “But I do hate to lose the horses.”

The Horse-Warrior Bond

I have had a lifelong connection with military men on horseback. My father died when I was very young, so I was partly raised by a succession of military Dutch uncles. One of them was Maj. Gen. Alfred G. “Tubby” Tuckerman. He told me, “Hell, Jim, I never wanted to go to war. The only reason I stayed in the Army was so I could ride. Between the wars [World Wars I and II], we spent most of our time playing polo, foxhunting and showing horses. I wasn’t much of a soldier, but I loved horses.” Gen. Tuckerman must have been more of a soldier than he would admit. Serving with the 1st Cavalry Division in the Pacific during World War II, he was awarded a Silver Star for gallantry in action.

He loved to have a few drinks and tell how he became a general. According to him, when the 1st U.S. Cavalry had its last mounted Division Parade at the outbreak of war, he disobeyed orders and rode his private mount rather than the charger the U.S. Cavalry supplied him.

I will let Gen. Tuckerman tell the rest of the story: “By God, I’m telling you, Jim, that charger was just too ugly for me to ride. We knew the days of the cavalry were numbered, and I figured this was my last mounted parade, so I rode my gorgeous four-year-old that I had just imported from Ireland. There were nearly 10,000 mounted troopers on that parade. I was only a major, but because I was on the General Staff, I rode up toward the front. Everything was great until the band struck up ‘Garryowen’ [a famous marching song for cavalry parades]. Jim, the moment the band played the first note, that four-year-old spun back, ran sideways through all 10,000 horses and riders and scattered them from hell to breakfast. Naturally, I was court-martialed and had to appear at a military judicial proceeding. The generals and colonels chewed me up one side and down the other but let me off with a reprimand. Then, as I saluted and started to leave the room, the general in charge stopped me as I got to the door. When I turned, he said, ‘By the way, Tuckerman, that was a hell of a ride you gave that four-year-old.'”

Gen. Tuckerman said every time he came before a promotion board after that, they would all agree he gave that Irish 4-year-old a hell of a ride and promote him to the next grade. I discounted his modesty because his record in the war spoke for itself. At the same time, his affection for horses shone through every word he spoke.

U.S. cavalrymen were not unique in their affection for their mounts. This is a trait that mounted warriors have shared through the ages. American Indians formed some of the finest light cavalry the world has ever seen. The few statements I have read from them regarding their horses show the respect and admiration they felt for them. Plenty Coups, a war chief of the Crow, said, “My horse fights with me and fasts with me because if he is to carry me in battle he must know my heart and I must know his or we shall never become brothers. I have been told that the white man, who is almost a god and yet a great fool, does not believe that the horse has a spirit. This cannot be true. I have many times seen my horse’s soul in his eyes.”

I have had a lifelong connection with military men on horseback. My father, Col. John W. Wofford, is shown here as a very young 1st Lieutenant at Front Royal, Virginia, in the late 1920s. You can see that the U.S. Cavalry was already trying to reconcile mounted combat with modern warfare. Note that my father is wearing both a sabre and pistol, along with his binoculars, his raincoat and his bedroll.

I have had a lifelong connection with military men on horseback. My father, Col. John W. Wofford, is shown here as a very young 1st Lieutenant at Front Royal, Virginia, in the late 1920s. You can see that the U.S. Cavalry was already trying to reconcile mounted combat with modern warfare. Note that my father is wearing both a sabre and pistol, along with his binoculars, his raincoat and his bedroll.Author Nathaniel Philbrick wrote in The Last Stand that at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, as the Indian tribes were about to start their final charge against Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry, “Seized with rage, Young Hawk stripped to the waist and prepared for the end. In anticipation of being killed and scalped, he unbraided his hair and tied it with eagle feathers. But first he must say good-bye to his horse. Wrapping his arms around the pony’s neck, he said, ‘I love you.'” Young Hawk survived the Battle of the Little Big Horn. His pony did not.

One of the most touching instances of soldiers’ affection for horses is contained in a post-Civil War letter written by Gen. Lee. His wife’s cousin, Markie Williams, had written to him that she wanted to paint a portrait of Lee’s warhorse, Traveller.

Lee replied: “If I was an artist like you, I would draw a true picture of Traveller; representing his fine proportions, muscular figure, deep chest, short back, strong haunches, flat legs, small head, broad forehead, delicate ears, quick eye, small feet and black mane and tail. Such a picture would inspire a poet, whose genius could then depict his worth and describe his endurance of toil, hunger, thirst, heat and cold; and the dangers and suffering through which he has passed. He could dilate upon his sagacity and affection, and his invariable response to every wish of his rider. He might even imagine his thoughts through the long night marches and days of the battle through which he has passed. But I am no artist Markie, and can therefore only say he is a Confederate grey.”

I was raised just off the military reservation at Fort Riley, Kansas, home of the U.S. Cavalry School. Chief, the last horse in the U.S. Cavalry, was still alive during my boyhood years. I remember hundreds of cavalrymen, and my strongest memory is their evident love for horses of every type. We should be thankful that horses are no longer expected to carry us into battle and can now content themselves carrying us to far more pleasurable tasks.

This article first appeared in the August 2012 issue of Practical Horseman.