Injury is the downside of equestrian sports, particularly when it comes to riding over fences, but ever-improving safety equipment lessens the danger. A big step toward that goal came today with word that more than $425,000 has been raised for research into U.S. helmet safety standards and creation of a system that will inform consumers through the sport-specific Equestrian Star Rating project about which helmets offer the most protection.

The U.S. Equestrian Federation, U.S. Hunter Jumper Association and U.S. Eventing Association have committed to the funding, along with a major matching grant from prominent eventing benefactor Jacqueline Mars. The U.S. Equestrian Team Foundation also has endorsed the effort. The Virginia Tech Outreach Helmet Lab, which puts together the star ratings for helmets used in other sports, will receive data on falls and injuries from USEF competitions as it conducts its research.

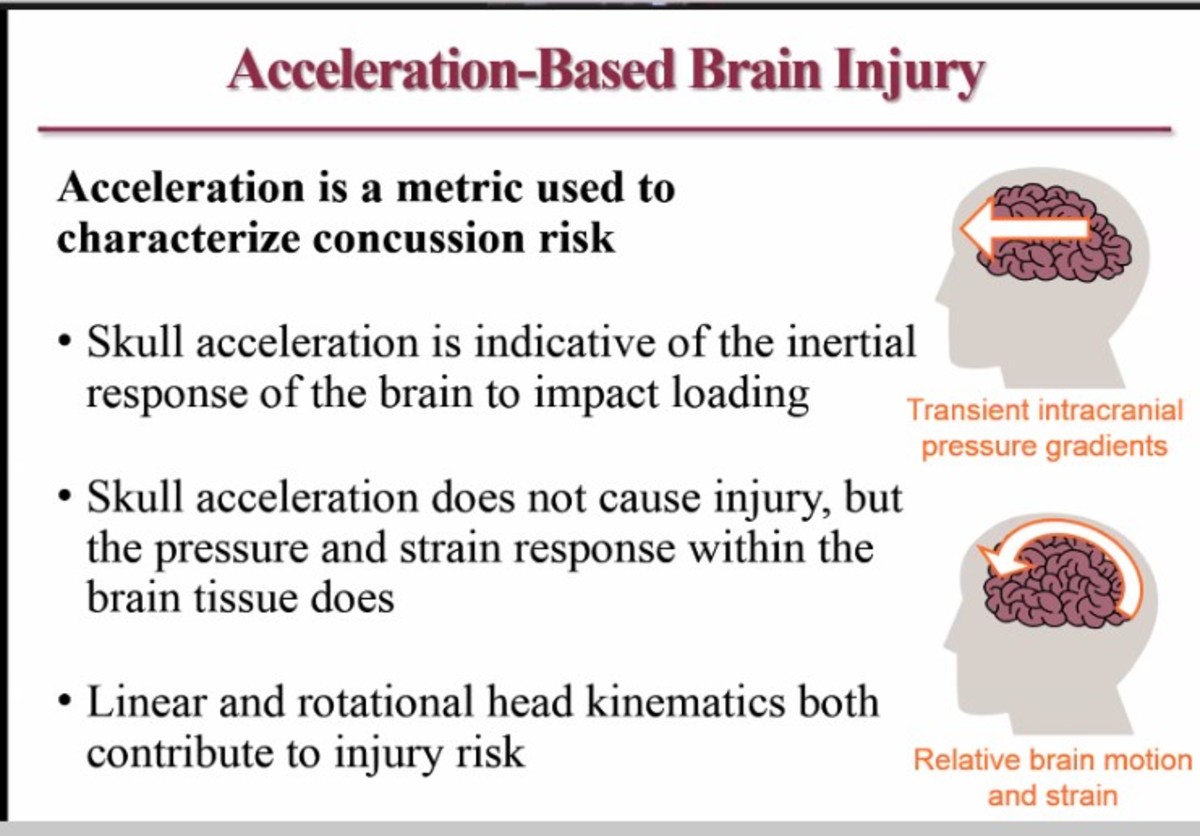

Speaking at the USHJA virtual convention today, the lab’s Dr. Barry Miller noted that while consumers can see by looking at a tag whether a helmet is approved by ASTM International (formerly the American Society for Testing and Materials), such accreditation is done on a pass/fail basis. That means those shopping for helmets don’t have more detailed information on how well each style surpasses baseline certification. The STAR system will alleviate the guesswork and enable buyers to determine which helmet is best for them. That’s key, since the researcher stated that one in five equestrians will suffer a serious injury in their lives, and horse sports are “the greatest contributor of sports-related TBIs” (traumatic brain injury) at 45.2 percent. Contact sports have the second-greatest percentage at 20.2.

The original goal for the project was to raise $450,000, but with so much of that already committed and fundraising continuing, work will go forward. It should run over 18 to 24 months, with several objectives: One is informing consumers of the relative difference between helmets in the context of lowering concussion risk. Another is to provide manufacturers with information about designs that can reduce the risk for riders whose heads may be as much as nine feet off the ground while aboard an unpredictable 1,500-pound animal that can go as fast as 40 mph, he said.

Other takeaways from the presentation:

• While 18- to 29-year-olds in all sports have the most TBIs, there’s a high proportion in the over-60 category of equestrians because riders continue longer in their sport than those who play games such as football and rugby. “The more you ride a horse the more risk you take,” said Dr. Miller.

• Dummy head forms will be used in the lab to test kinetic energy, with the star score a summation of impact tests.

• Data analysis and evaluation for ratings will be done on a broad cross-section of helmets, with a star-rating webpage available.

• Having the ratings will incentivize helmet manufacturers to compete and make better products

The Future of Body Protection

In another of the afternoon’s safety presentation, Danielle Santos, director of sales and partnership at Charles Owen, offered a lot of good information about body protection. Although this once primarily was the province of eventers, air vests have been adopted by a number of jumper riders since Olympic show jumper Kevin Babington suffered a devastating spinal injury in a fall during a grand prix more than 14 months ago.

Calling safety equipment “the last line of defense” against injury, Danielle emphasized that “absorbing impact is Job One.” An air vest deploys 0.1 seconds after it is triggered, and will be fully inflated by the time the rider hits the ground.

She explained there are three varieties of protection that can be worn: The body protector/safety vest, which she called “a foundation garment”; the air vest and the shoulder protector. While show jumpers are wearing just the air vests, Danielle compared it to an air bag in a car, while the body protector would be like the seat belt. Neither one can prevent broken collarbones, a common injury in riders, but the shoulder protector, worn underneath the vests, helps in that regard.

Other takeaways from Danielle’s talk:

• In buying this equipment, the age and sex of the rider need to be considered, along with the evaluation of their riding ability, the potential need for greater protection and the cost, which can be considerable.

• Test the air vest in the store to make sure nothing happened to it during shipping and that it deploys. That way, you don’t have to pay for the gas canister that inflates it, which can cost $40 to $50.

• An air vest will not protect the wearer from the stud on a horse’s shoe or hitting a piece of board, both of which could puncture it. That type of protection is the job of the “foundation garment.”

• Vest fitting is important; it needs to be sized so you can tuck and roll after a fall.

Check out yesterday’s story on the new Outreach Program for grassroots riders and training tips for the equitation ring, and check back for more from the USHJA Annual Meeting tomorrow.