When I train students and horses, I focus on clear rider aids, straightness, honest responses to the rider’s leg, adjustability out of the turns, timing and composure under pressure. The following three exercises address all these qualities—and more. They are suitable for riders of any level, from the low amateurs to the grand prix.

Exercise 1: The Cavalletti Clock

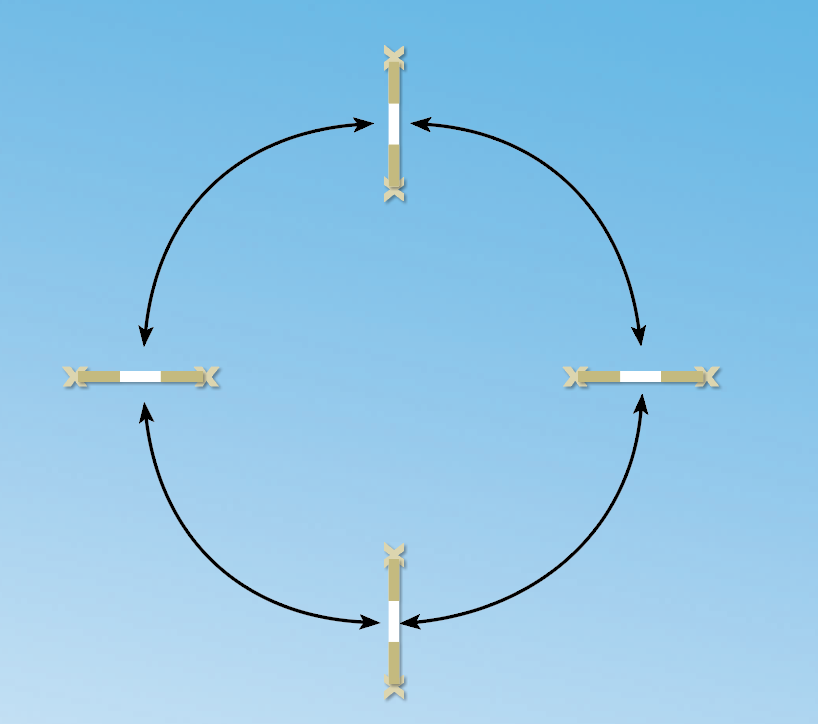

Setup: Set four low cavalletti or ground poles at the 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions of a comfortable-sized circle (see diagram, above). I always use striped poles because that helps in finding the center. Don’t worry about the exact distances between the poles.

How to ride it: Starting at the walk, ride a circle over the four poles, aiming for the center of each one. Sit lightly, use inside leg to outside rein and look at the next pole as you are preparing to go over the one in front of you. When that’s going well, turn around and ride the circle in the opposite direction. Gradually build up to doing the same at the trot and canter. Don’t count strides; just ride from feel. Practice the exercise both sitting and in two-point.

Purpose: A good warm-up and test of the rider’s aids

Explanation: This exercise makes riders use their aids effectively and be very, very clear with their horses about what they want; that is, to aim for the center of the poles. We do variations of it at different heights and different speeds, always keeping the cavalletti low.

Exercise 2: Short Turn to Liverpool Bending Line

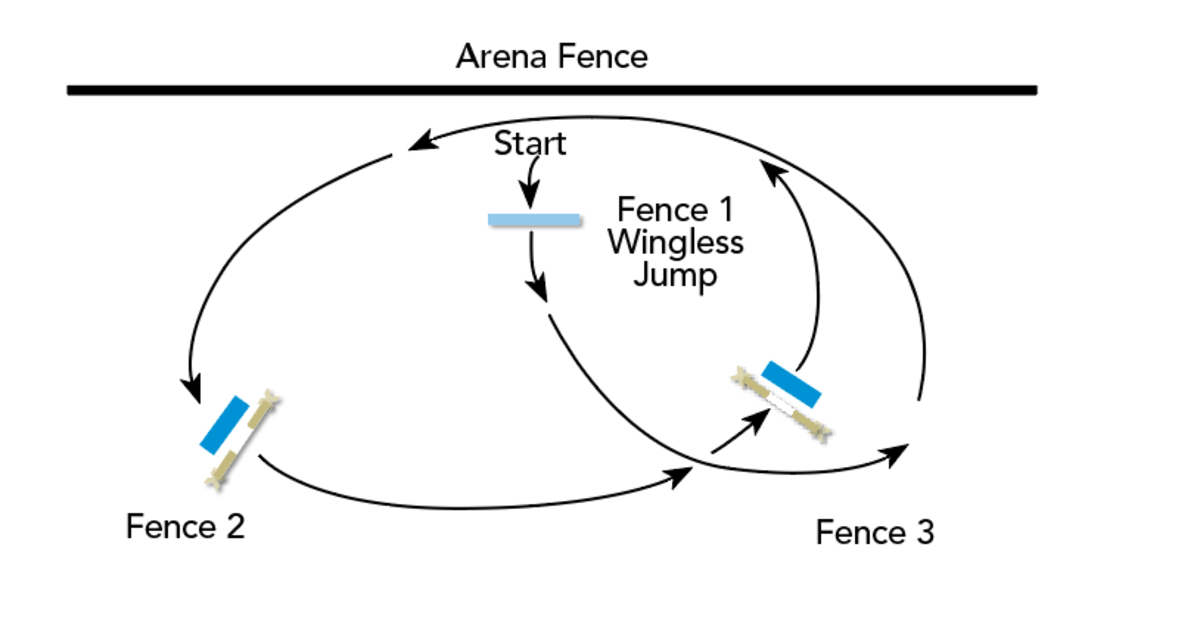

Setup: Build two small verticals at an angle from one another of more than 90 degrees to create a bending line (see diagram, below). Don’t worry about the exact distance between the verticals. Set a liverpool in front of one of the verticals and a second liverpool behind the other. Place a small, unusual-looking wingless fence about equidistant between the two liverpools, but closer to the arena rail and parallel to it, so you have to make a short turn immediately before the fence when jumping it in the direction away from the rail.

For the two verticals, again, I like to use rails with stripes in the middle, because I want riders to be aware of not letting the horse drift left or right. This also enables them to see where they’re going in terms of a focal point. I always make the small, wingless jump something different. This serves as a distraction. It is a good way to “take the horse’s temperature”—to see if he’s listening—and its slight spookiness requires the horse to be in front of the rider’s leg.

How to ride it: Begin by circling over the small, wingless jump sev-eral times off the left lead, landing on the left lead and keeping a precise track. Then do the same thing several times off the right lead, then figure-eight it until you are comfortable in both directions. Aiming to jump in the middle of all three fences, begin by cantering on the left lead, over the wingless jump, heading away from the arena fence/wall. Then ride around Fence 3 and bypass the wingless fence to get to Fence 2. Continue on a circle jumping the two liverpools, bypassing the wingless fence. Jump until you can do three stride variations without changing tempo. After that, jump the wingless fence on the right lead and go clockwise over the liverpools.

Start by jumping the liverpools straight, using the stripes on the poles for a guide. Once you’ve done that, take the first liverpool on an angle, then continue on a bending line to the second. When you’re comfortable with what you’ve done, take both liverpools on an angle, so you’re riding a straight line between them, rather than a bending line.

Once you can jump the fences middle to middle comfortably, then you can start playing with striding variations. Add and leave out strides depending on your horse’s character and what he needs in his training. (For a horse who’s very hot, though, I wouldn’t leave out strides.) Keep changing it. Depending on your level and that of your horse, you could ride anywhere from 10 to eight strides between the verticals, and from five to three strides from the arena rail to the wingless jump. It’s important that this fence is short off the turn to truly test your horse’s trust in you.

Purpose: Teaches horses to be straight and aim for the middle of a fence while determining if they are honest off the leg on a slow pace off a turn

When you ask, your horse should answer. This exercise also teaches riders to keep their horses’ bodies straight and look ahead to the next jump without feeling rushed around turns. It helps develop a certain amount of trust between horse and rider. Part of the exercise is going long to short and short to long, getting the horse turning and supple and in front of the leg. This requires using all of your aids to direct your horse’s neck, shoulders and body while supporting him with your outside leg.

Explanation: This is a mini jump-off you can create at home within your comfort zone. It will teach your horse a lot about coming off a short turn. The jump heights are not important. And, with the angles, the distance between the liverpools isn’t important. I want to see that the horse trusts the rider. What I care about is that you control your horse and that you are able to soften your contact gradually off the ground. People get too worried about distances. Instead, focus on using your hands, seat and legs to make your horse straight. That way, by the time you get to the last stride before the fence, it’s a following stride and the biggest stride. This allows the horse to jump the fence with the right balance and rhythm.

With a liverpool in front of the first vertical, you have to ask the horse to come forward; it’s a bolder jump going into the bending line. Coming out, with the liverpool behind the second vertical, it’s a careful jump. It’s good for the horse and rider to have to jump into the bending line boldly and then regulate the stride and rhythm to jump out over something that is careful. So you’re asking for a little bravery and then a little bit of control. You’ll find that it’s harder to practice this than it would be to ride the opposite configuration: riding carefully in over a vertical with a liverpool behind it and then boldly out over a vertical with a liverpool in front of it.

I also want to emphasize the value of the turn to the unusual-looking jump. This challenges you to use your eye—looking ahead to the next jump—without being rushed. People don’t practice this type of turn very often, but you’ll find it in jump-offs. When you get in the ring, it’s too late if you haven’t spent time on this in training. We practice all the time, making the horses turn, then either leaving out strides or adding strides.

Exercise 3: Fan Double Bounces to Angled Jump

Nancy Jaffer

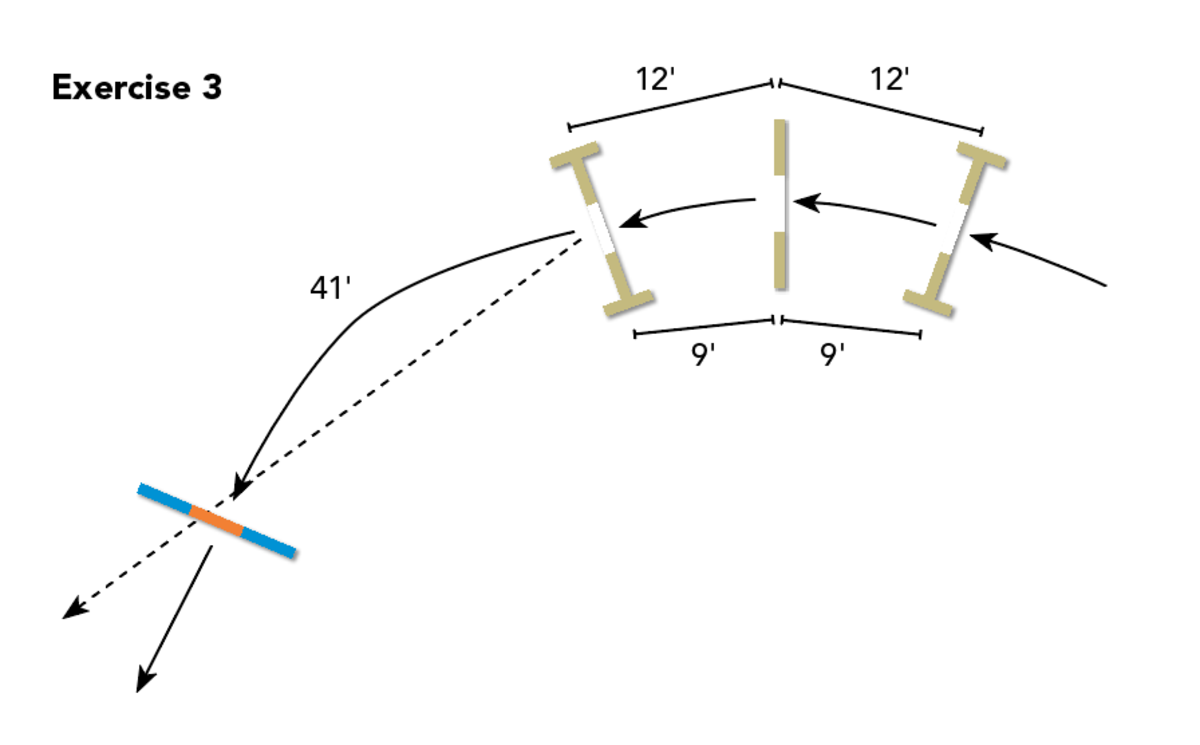

Setup: Build a one-stride fan combination out of two verticals, making the inside standards slightly closer together than the outside standards so your horse has to jump them in a bending line when going from center to center (see diagram below). Place a ground pole exactly halfway in between the verticals. Adjust everything so the distance between the outside standard of the first jump is 12 feet from the outside edge of the ground pole, which is then another 12 feet from the outside standard of the second jump; the equivalent inside measurements are 9 feet. Set the rails of the verticals as low as 3 or 6 inches off the ground. This exercise should never be done over fences higher than 3 feet, and no higher than 1 foot for an amateur.

Then build a slightly angled jump, without wings, 41 feet (three strides) from the second vertical, measured center to center on a bending line. I like something without wings for this final fence, which could even be a narrow fence, because I’m looking for the rider to direct the horse to the middle using hands, seat and legs, rather than relying on the jump wings.

How to ride it: Canter to the center of the first vertical. As you go through the double bounces, focus your eyes on the wingless jump. After the second vertical, land, sit up and close your fingers to control the first two strides, so the last stride is the biggest stride. Avoid taking back on the reins three times—which is a natural reaction for many riders. I want it to feel like you and your horse are totally together, with you having control. The horse is going to do it, but it’s difficult to do it well and make it three perfect strides.

Ideally, I want horses to jump the middle of each fence, which makes the bounce distances each 10½ feet. This is a comfortable distance over small fences. However, if your horse has a big stride, you may find it easier for him to stay on the outside track.

The wingless fence can be jumped on a bending line (solid line) or you can ride a straight line to it (dotted line).

Purpose: Teaches the rider that being patient and staying light with her seat helps to balance the horse

Explanation: If you can walk, trot and canter and you are secure in the saddle over small jumps, you can do this exercise. It involves the ability to keep your composure and not be rushed, to understand timing and not allow the horse to get there too early or too late. The double bounces mean lots of riders could lose their balance. I want you to catch your balance without hanging on the reins.

As you’re working on your core, your rhythm and the horse’s composure going through the bounces, you’re also focusing on the jump ahead, figuring out your approach to it and then fixing the distance to it early enough that the last stride is the longest stride.

The very small jumps are just enough to make your horse engage his hind end a little bit more than he would when cantering on the flat. While riding the double bounces, be patient, stay in one place and stay light with your seat, letting the horse come up to your chest. I don’t want the rider doing a rocking motion.

The three-stride distance to the angled jump is more difficult than a one-stride—which just happens—or a two-stride—which kind of just happens. Three strides between fences takes more control and more ability to place the horse. I like this distance a lot because it gives the horse a chance to get away from the rider. In other words, it’s not automatic. It requires you to be really sharp and react on the first stride, not the third stride. In competition, if you’re coming off an oxer-to-oxer combination to a plank, or a water jump to a skinny, reacting early enough—and in the correct way—is important. It’s not about being rough; it’s about being correct.

Team Dello Joio

The unique father–son team of Norman, 63, and Nick Dello Joio, 27, is a study in contrasts, a jumping legend partnered with an up-and-coming grand prix rider.

Trained by U.S. Equestrian Team coach Bertalan de Némethy in the 1970s and ’80s, Norman rode on the gold-medal team at the 1979 Pan American Games aboard Allegro, won the 1983 World Cup Final with I Love You, earned an individual bronze at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics on Irish and represented the U.S. in multiple Nations Cups. His many famous mounts also include Johnny’s Pocket and Glasgow, his 2004 Budweiser American Invitational winner. Since transitioning from competitor to trainer, he has coached many successful riders, including the Mexican team.

Nick began taking an active role in the family’s Wembley Farm business, based in Wellington, Florida, when he was 20. He had trained with equitation coach Missy Clark and received some help from other trainers, but Norman has been his main teacher. Knowing how tough it is to make it in the horse business, his parents didn’t push him to follow in his father’s footsteps. “I’ve been totally honest with him,” says Norman. “I didn’t encourage him to do this sport at all. He came to it wanting to do it. We were kind of hoping that he would go to school and do something else.” While Nick has three and a half years of college under his belt, he wound up following his parents’ lead.

One challenge he faces is acquiring quality mounts, despite his good eye for talent. “I’ve ridden a lot of nice horses,” Nick says, “but I’ve never kept them.” While in Mexico, he spotted Darry Lou, with whom Beezie Madden later won the world’s richest grand prix, the $3 million CP International, at Spruce Meadows, in Canada, in September. And he retrained HH Carlos Z before that horse went to McLain Ward. “We’ve had a lot of quick turnarounds and quick sales, or we fix and then sell them.”

“That’s been a necessity,” explains Norman. “I was lucky enough to have a lot of good backers and sponsors.” Today, however, people who might have bought horses for a professional rider in another era want to do the riding themselves. Even so, he says, “We have friends who help us out whenever possible to keep Nick mounted.” While that means riding lots of different horses, many of whom are not top-level candidates, “that’s not such a bad thing,” Norman contends. “We will sometime come across a really special horse and I think he’ll be prepared.”

Nancy Jaffer

Meanwhile, Nick shares training duties with his father. The demands of Wembley’s business range from sending 10 or so riders to shows such as Spruce Meadows to managing as many as 50 horses at a Florida show. “Nick is a huge asset,” says Norman.

The young trainer describes Wembley as a place where “you can get the strict instruction to make you a better rider, but it’s in a more laid-back, family-type environment where there’s no threat of pressure.” He and his father handle the horse side of things, while his mother, Jeannie, takes care of other aspects of the business. “When you get to be a part of our horse family, you know all of us,” says Norman.

Becoming business partners “has been a learning experience for both of us,” he adds. “It’s going well because we know each other very, very well. I have to accept that what worked for me doesn’t mean it will work for him. Knowing he’s a totally different personality and rider has been an education.”

Nick points out, “Dad’s a lot quieter than I am, a little more internal.” Even so, Norman is less intense than he used to be. He acknowledges, “When I was competing at my best, I had blinders; I didn’t look left or right. Since I’ve stopped riding competitively, I try really hard to put myself in other people’s shoes and try to understand that so much is about perception. How they perceive something to be easy or difficult is not how I would perceive it, and that doesn’t mean it’s good or bad or right or wrong. It’s just different. Part of me being a better trainer is to recognize that.”

Norman still hops on a student’s horse if necessary. “Some people learn a lot more from a visual than verbal instruction, so I still have the touch to do that, to show exactly what I’m saying. I do that a lot,” he says, noting how much he still enjoys riding. “Sometimes I miss competing, but in order for me to compete, I would have to put my blinders back on. It would require dropping a lot of things that are important to me now.”

While Norman’s powerhouse resume may make him seem less approachable to some potential students, he insists it shouldn’t be the case. “I deal with a lot of people’s emotions,” he says. “It’s 99 percent confidence when you get to a certain level. I’ve learned to deal with all that.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2019 issue.