Know how it feels when you’re running downhill and you start to tip forward and go faster and faster? It takes a bit of time to get your feet back underneath you, regain your balance and slow down. That sensation is almost exactly what your horse feels every time he lands from a jump. To get his hind end back underneath him and regain his balance so he can canter softly away—what I call “finishing the jump”—he needs time, which you give him by staying over the center of balance and maintaining a nice release.

Unfortunately, many riders have fallen into the habit of pulling on their horses’ mouths in front of the jump, in the air or on the landing. Not only do the riders disrupt their horses’ balance, they keep their horses from concentrating on what they have to do because they’re worrying about what they’re going to feel in their mouths. Instead of landing softly and cantering away in balance, the horses may race, buck or get unruly.

As with any habit, riders can’t fix it until they become aware of it. That’s why I’m going to give a simple jumping exercise where you trot in, release as you jump a small crossrail, land and maintain your release for three more strides as you canter away over three ground poles. I’ve had a lot of rapid success with this exercise, even with professionals who’ve fallen into the pulling habit because it does two things

at once:

- It opens your eyes to how quickly you want to pull on your horse’s mouth after a jump.

- It helps you form a new, softer habit where you wait to take a feel until your horse has had at least three strides to regain his balance and finish the jump.

And talk about breaking a vicious cycle—underreacting always goes a long way toward quieting a horse. Once he stops worrying about you pulling on his mouth in the air or on the landing, he’ll realize he can focus on making and finishing a nice jump instead.

Best of all, because the jump is very small, you can repeat the exercise until you get it. And that won’t take long. In fact, the first time through, you’ll recognize the bad habit of wanting to pull. Do the exercise a few more times while you stay over the center of your horse and maintain a release—you’ll have the ground poles to help you remember—and unless you really have issues with your position, you should be able to break this habit in one session. When that happens, you’ll be well on your way to helping your horse create the perfect jump.

Benefits

- Your horse becomes more alert, confidently sizing up the jump and “hunting” the fences.

- His rhythm and pace stay consistent, and he arrives at a comfortable takeoff spot and remains unchanged on the landing side of the fence as he smoothly regains his balance.

- Because he trusts you not to hinder him in his mouth in the air or on landing, he uses himself generously and completely, jumping high into the air and maybe even giving you a bit of extra room between the fence and his legs, and he stretches his neck roundly forward so you have a nice contour from the tip of his nose back to his tail.

- He lands softly, not “in a heap,” which to me means he lands dead and going nowhere, either because you’ve fallen back against his mouth or he doesn’t know how to carry forward after the jump.

Who Can Do It

Any rider who has a solid two-point position and has started jumping can try this exercise.

Setup

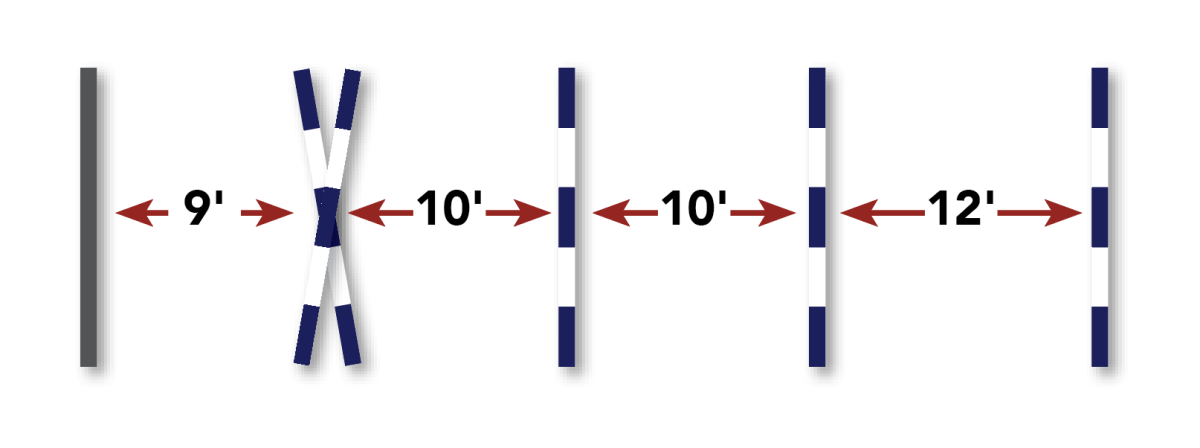

Following the diagram below, put down a trot ground pole. Nine feet beyond it, build a small crossrail, which helps you stay in the middle. Set three ground poles beyond the crossrail, the first two at 10-foot intervals, the third at 12 feet. Allow several more horse strides after the last ground pole before the end of the ring. These measurements should work for most horses. Since I don’t know your horse and how he moves, adjust the poles until he can land from the crossrail and jump the first pole comfortably, then reach just a little bit for the next two, which will help to encourage you to stay over, follow and not pull.

Tips for Success

- Check your position. With your leg relaxed and hanging down, the bottom of your stirrup iron should just touch your anklebone—proof that your stirrup is the right length to drop your weight down into your heel, maintain a correct knee angle and rise just enough out of the saddle in your two-point position. Also be sure to keep your elbows in front of your hips and your hands in front of your chin and holding the reins so your thumbs are on top and slightly angled inward.

- Think for yourself. I’ll give you some guidelines, but your horse may be the type who just naturally wants to go faster than other horses. In that case, you’re probably going to have to take a feel of the bit sooner. If he tends to be a little hot, you may need to take a settling-down walk break each and every time you do the exercise. And if he’s a dead-lazy horse, you may want to wake him up by coming right back to trot and riding the exercise several times in a row without a break.

- Remember to think about what you need to do after the exercise. If you have a really big ring or if you’re riding out in a field, you can leave your horse alone for many strides after the jump. If you’re riding in a small ring, you have to pick up the reins and get your lead change (if you need one) before the corner that’s coming up fast. But even in a small ring, if you teach your horse that you’re going to allow him to canter away from the jump and regain his own balance, he’s going to be more receptive to what you have to say because he has no reason to worry about what’s going to happen to his mouth.

How to Ride It

- Before you start this exercise, warm up your horse on the flat. Then, tracking right, pick up an energetic posting trot with quite a bit of pace and nice, long trot strides. Get up in two-point about five strides before the trot pole.

- Keep your leg on and a small feel of your horse’s mouth to encourage him to trot to the pole, get to the base of the crossrail and balance upward as he jumps. Look ahead to where you want to go after the jump—it’s OK to track it with your peripheral vision.

- As your horse jumps, relax and allow him to close your hip angle. Keep your hands in front of your chin so that you meet his neck with your knuckles, pressing them on both sides of his crest as he creates a release in the reins. Maintaining your two-point position, keep weight in your heels, stay closed in your hip angle and keep those knuckles pressed into his neck as he lands and canters away over the three ground poles.

- After the third ground pole, make a decision. If your horse stayed quiet and cantered away without grabbing, yanking or racing, just softly, gradually, smoothly start to re-establish contact on the reins. Before you get to the corner, come back to the trot and repeat the exercise. If your horse got quick or upset, quietly bring him back to the walk, walk for a while to calm him down, then pick up the trot and repeat the exercise. Slowly but surely, by maintaining your release and NOT snatching at him or interfering with his jump, you’ll convince him that he has nothing to fear from your hands. And because you’re giving him nothing to lean against, he’ll become accustomed to rebalancing and holding himself up.

- Once you are reliably staying closed and pressing down into your horse’s neck over the ground poles and he’s calmly, softly finishing each jump, build the crossrail into a small vertical. When that feels good, canter the exercise. Take away the trot pole and set the three ground poles about 11 to 13 feet apart, depending on your horse’s stride. Even though you’re cantering now, try not to get excited and start pulling. Focus on holding your position to the crossrail and on maintaining your following release on the back side of it.

- When that is going well, take away the ground poles on the landing and maintain a release while your trainer or friend counts to three for you. Then do the counting yourself.

- Finally, canter a line. I think you’re going to find that when your horse knows he has nothing to fear from your hands, he’ll lope down the lines like he has lots of stride—and let’s face it, your show-ring trips are going to be that much smoother when you’re not running down the lines.

Patrick Spanton is an accomplished trainer and rider whose clients and horses have won hundreds of A-rated championships and medal finals. He was raised in a non-horsey family in Vancouver, British Columbia, but at age 12, he started working for Leslie Reid, a two-time Olympian and Pan American Games gold medalist. When he was 18, he began working at a show-jumping sales barn near Aachen, Germany. Before starting Patrick Spanton Training Stables, he was the trainer and rider at Rainbow Canyon Ranch and worked alongside Mary Gatti. Patrick currently lives outside of Rio de Janeiro where he trains high-level jumpers and offers clinics throughout the United States, Canada and Brazil.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of Practical Horseman.