The nice thing about my job is that I get to travel; the bad thing, of course, is that I have to travel. My clinics take place around the country, which means I get to see a lot of different people in a lot of different places. It also means I spend a lot of time either in airports or driving down interstates. People are feeling better about themselves because of the growth in the stock market, which has created a rise in consumer confidence; everywhere I go, it is crowded, especially airports and highways. I was in Los Angeles earlier this summer and the entire community was in cars, going somewhere. Crazy.

People with rising prosperity are good for the clinic business, and I have been taking advantage of it. Clinics are a source of income (which is nice) and I enjoy them (which is even better.) Right now I am teaching across the disciplines at every level. I enjoy the contrast of going from a specialty clinic at a well-known venue, attended by serious young hunter/jumper riders (all jumping 1.0 meter or higher) who were pre-selected for that clinic, to an unfamiliar new facility hosting a clinic attended by “nervous novices” who need the rails spray-painted on the ground if they are to be successful.

Given all this, I want to share with you some things I have noticed this year, and talk about habits and trends—some new and some old, some universal and some specific to a discipline—and how, when it comes to really good riding, the disciplines overlap more than they differ.

Connection Comes First

Regardless of the discipline, I always begin my clinics by talking about the rider’s connection with her horse. However they say it, all coaches talk about this early on. The late Bill Steinkraus was very articulate and very particular about the words he used to describe sensations.Although he agreed with the concept of “connection,” he didn’t like the word. In one of our many discussions, Bill told me, “… I have always felt that ‘contact’ and even Bert’s [Bert de Némethy’s] ‘connection’ are relatively clumsy, inexpressive words and prefer the French ‘appui,’ defined as ‘the reciprocal sentiment between the horse’s mouth and the rider’s hand.’ Good hands and l’appui bon come together.” That’s heavy stuff, and I’ll come back to it in a minute.

See also: Goodbye to Cap’nbilly

Specialist vs. Complete Horseman

I recently taught a jumper clinic for the United States Hunter Jumper Association, and I had a ball. The riders had been pre-selected, which raised their level of expertise above that in my typical clinics. I’ve been planning this column ever since that exposure to good young riders from a different discipline.

Charles Mann

It only makes sense that good riders from different disciplines share certain universally desirable characteristics, yet display different faulty habits. For example, my jumper kids were far more accurate in the approach to obstacles than young eventers, who will never fit in another stride if they can leave the ground now. On the other hand, too many jumper riders “wimp out” when their horses gets sticky to the liverpool. In certain situations, a rider has to make it happen, not watch it happen. I can always trust event riders to get “stuck in” when that situation arises, but they will look crude as they do it.

Riders from either discipline will have both good and bad habits, but my problem is I am looking for a complete horseman. In my mind, this rider is comfortable and successful across the entire spectrum of the three Olympic disciplines: dressage, show jumping and eventing. Think of Gen. Harry D. Chamberlin, who won Olympic medals in both show jumping and eventing, or Gen. Frank Henry, who won Olympic medals in eventing and dressage. In the modern era, think of Germany’s Michael Jung or Ingrid Klimke, who win Olympic eventing medals and also excel at grand prix show jumping and Grand Prix dressage. My overriding ambition for my riders is that when they “graduate” from my program, they are able to ride a wide range of horses, able to ride a horse in classical collection, then school a timber racer, then come back that night and win a puissance class.

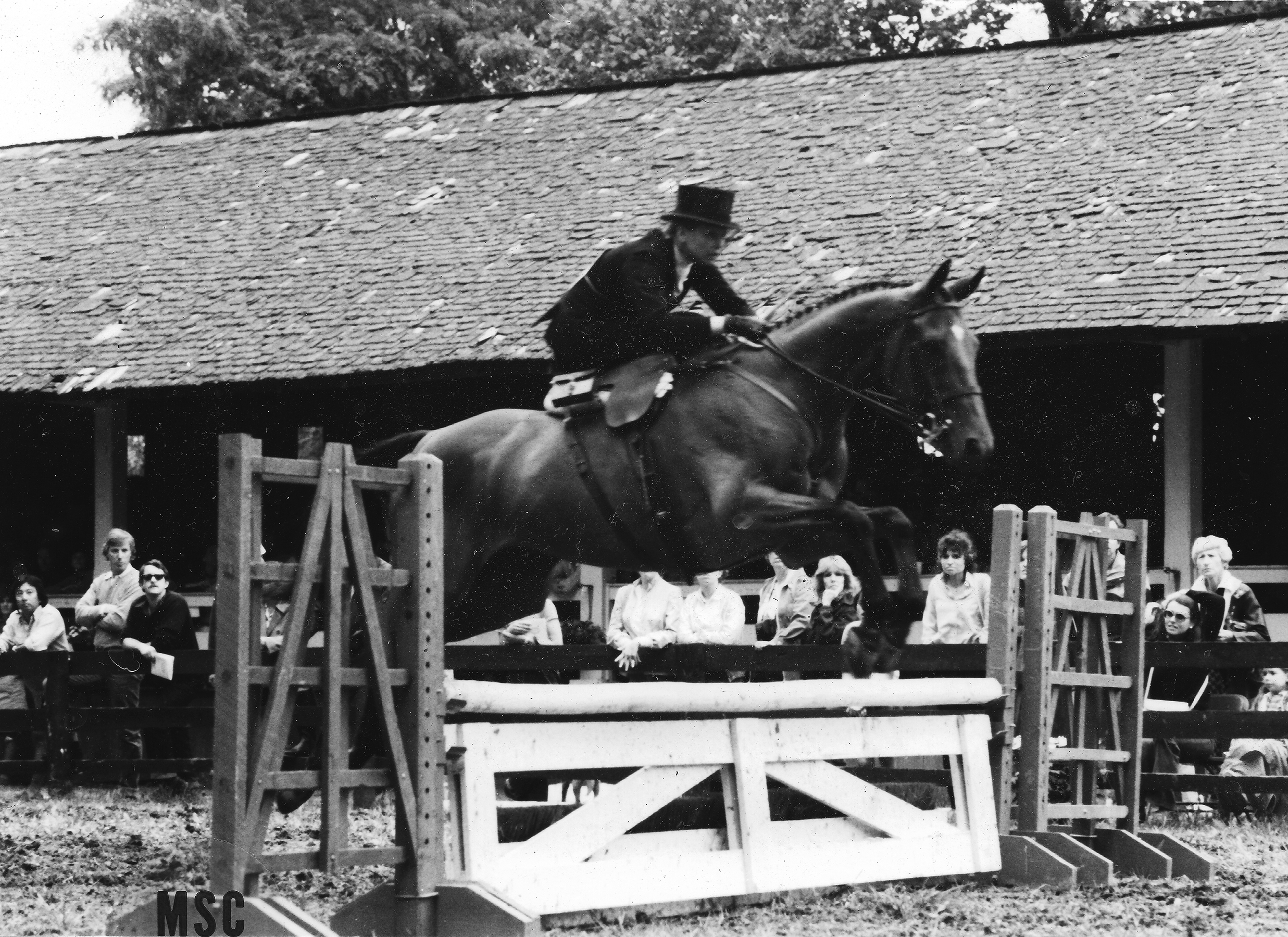

Mary Susan Coleman

That’s an impressive range of experience, but it’s possible. Just a couple of examples: In the summer of 1966, Kevin Freeman (Olympic silver medalist in 1964, 1968, 1972) rode dressage in a high state of collection at Gladstone one morning, schooled a timber horse really well that afternoon and then at the Branchville, New Jersey Horse Show that evening jumped a 6-foot-6 puissance wall. A few years later, Joy Slater Carrier (the first woman to win the Maryland Hunt Cup) won the ladies’ sidesaddle class over fences at the prestigious Devon Horse Show. She next drove down to the Fair Hill (Maryland) racetrack, where that afternoon she won the novice timber race on a very sketchy young horse. She got back to Devon that night in time to win the Amateur Owner Jumper Stake. Now that’s a rider. Nina Fout won an Olympic medal eventing, rode races and won sidesaddle classes over fences.

I want my students to eventually become the next Harry Chamberlin or Frank Henry, the next Kevin Freeman or Joy Carrier. I watch them carefully, always busy identifying strengths and weaknesses in each one. I don’t confine my observations to the parameters of each discipline; I make mental notes about suggestions for that rider to fill in the blanks in her overall education. I expect jumper riders to be more accurate in the ring than eventers, while I expect eventers to deal with banks, ditches and liverpools better than jumpers. But I can expect both disciplines to also display gaps in their path to becoming a complete horseman. When I criticize either discipline, remember it is because I respect and admire both; I just want them to get even better. Throughout this article, you will notice that I don’t discuss the good and bad traits of pure dressage riders. I have talked a great deal about dressage, both its good and bad aspects, in past columns and I will again in the future. I don’t mention it here because I consider dressage to be such an integral part of both show jumping and eventing.

A Few More Observations (And Gripes)

Obviously, there are other trends and habits I notice while watching students who are adept at different disciplines. For example, event riders have a fairly good understanding of dressage, but when jumper riders start to warm up their horses, it’s obvious to me they don’t have the right tools for the job.

I have noticed that a jumper rider’s turnout is usually impeccable. When they walk into my arena, they look like a million bucks. Their horses are clean, their tack is clean and their boots have just been shined. Possibly this is because they have to appear “on stage” on a regular basis. On the other hand, eventer turnouts tend to reflect their casual, outdoors, “git ’er done” ethos. Unfortunately, too many of them overdo this and show up in my arena looking like homeless on horseback. It is not enough to just get something done, because there is always someone else around who can get it done in a better way. You may have been taught you could be “crude but effective,” but the truth is that crude is not effective. A meticulous attitude will beat crude but effective every time. I’ve been doing clinics for more than a half-century and have finally exhausted my sense of outrage upon seeing a shabby rider on a dirty horse; I no longer comment on their appearance. In addition, I notice when an unfit rider who is obviously a menace to her horse comes into my arena. I don’t say anything, but I notice … I notice.

It pains me to even talk about unfit riders and poor turnout, because I wasn’t brought up that way. I watched Bert de Némethy ride and train for 50 years and never once saw him with yesterday’s dust on his boots. Never. Jack Le Goff was the same; his turnout was never fancy, it was just immaculate. Aristotle said, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” Bert and Jack dedicated their lives to excellence, and they demanded excellence in everything their team riders did with horses. While I was training with the USET, our turnout—and our horses’ appearance—was excellent every day. That appearance was a visible manifestation of our commitment to excellence. If you are a young eventer and you want to improve, to “make the team” and contribute to your country’s return to success as a nation … make your bed every morning. Every morning. Shine your boots every time you ride. Every time. If you are dealing with the most magnificent creature in the world, you have an obligation to excellence.

Douglas Lees

Now … Back to Connection

That obligation extends to our connection with our horses. When I say “connection,” I mean more than just your contact with your horse’s mouth. I know what Bill Steinkraus meant, with his comments about l’appui bon, but his thinking was always too sophisticated for me. I try to make things as simple as possible when I talk with my riders about various things. (There is a quote attributed to Albert Einstein: “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.”) When I say connection, I am simply talking about your connection to your horse in every aspect: your seat, your legs, your hands, everything.

One of the first things I do when teaching a jumper clinic is make my riders drop their stirrups and then follow the motion of their horses’ back with their backs in all three paces. The jumper riders I deal with have a “picture-perfect” position … at a standstill. If you take a still photo of them, they look terrific. But once they move off, you will see that their backs are not moving in harmony with their horses’ backs, and their elbows are not softly following their horses’ mouths. Their connection with their horses’ backs and mouths is flawed, which means they cannot truly move in complete harmony with their horses. What’s the answer? Simple—we can put a man on the moon, but we can’t sit well until we work without stirrups.

OK, I’ve identified weak areas in both disciplines; what about the similarities? First of all, I mentioned that my jumper clinics’ participants are usually pre-selected—but really, anyone who signs up for a clinic is already pre-selected. If they are motivated enough to accept personal criticism from a stranger, they sincerely want to get better. When I find a rider with that attitude, I don’t care what level they are at right now … there’s hope for them to improve. I would say that attitude is universal across the disciplines, and it’s a good trait for any rider to have.

Please DO NOT Post the Canter

Of course, there’s always a dark cloud for every silver lining. In this case, the dark cloud you see hanging over my forehead as I watch my next group warm up is me, thinking, “Who taught these young idiots that it’s okay to post at the canter?”

Think about it for a minute. The horse is cantering quietly towards an obstacle with his ears up, assessing his situation, making value judgments about whether he should stand off or come in close when he jumps. In the meantime, the rider is alternating between falling forward onto the horse’s neck and dropping the contact, then in the next instant falling back onto his seat bones, banging his horse on the back and slightly bumping his horse in the mouth. (Note that my criticisms are phrased in the male gender. Since 88 percent of my reader demographic identifies as female, this means only 12 percent of my audience will take my critique personally. All the ladies can safely say to themselves, “Surely he can’t be thinking about me!”)

For more adept practitioners of posting at the canter, I would point out that the steadier the horse’s head and neck in the approach, the more accurate the rider’s eyes will be in the preparation for their jumping effort. However, when the rider is posting the canter, their eyes are getting closer to, then farther away from, the jump, during each stride. Determining a stride on the way to a jump is complex enough without introducing another variable. Posting at the canter now seems to be a universal habit throughout the country and throughout all the jumping disciplines. I hate it; please quit doing it.

While I am dealing with my pet peeves, let’s talk about bling (ostentatious clothing and jewelry, as if you didn’t already know that). When I see a rider sporting bling, it tells me all I need to know about her. They want to draw attention to themselves, rather than direct attention to their horses, where it should be. The last time I went to an event, the dressage judge was so blinded by the sparkle of the rhinestones a poor horse was wearing that she gave the combination a bad score because she couldn’t see them. At least jumper riders use real diamonds for their bling. Of course, outside the ring they need armed guards for their bling, but I guess it is a small price to pay, to make sure people are watching you and not your horse.

The last time I looked, this was a classical horse sport, one where we are intimately connected to our horse at all times, thus allowing us to enhance each horse’s talents and abilities to his greatest potential. Let’s keep it that way.

Based at Fox Covert Farm, in -Upperville, Virginia, Jim Wofford competed in three Olympics and two World Championships and won the U.S. National Championship five times. He is also a highly respected coach. For more on Jim, go to jimwofford.blogspot.com.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Practical Horseman.