Very few people change the world. It takes genius to see in a different light what everyone can see, and then to say what no one has said. Such a man was Federico Caprilli (1868-1907), arguably the most transformative rider to ever throw his leg over a horse. I have read about and learned from fabulous horsemen who improved my technique and deepened my appreciation for the training and riding of horses. I hope that you revere William Steinkraus, Jack Le Goff, Bert de Némethy and Col. Harry D. Chamberlin—those giants of our sporting world—as I do. Regardless of the respect I feel for them, Caprilli stands head and shoulders above them all.

Beginning in the late 1890s, after centuries of studied and purposeful abuse of horses by mankind, Caprilli invented a system of training that was humane in every aspect. Certainly, the revolutionary new riding technique he developed is one we utilize to this day. However, the relief from suffering that he brought horses is the true key to his greatness.

A Simple but Revolutionary Idea

Before Caprilli, the horse, while jumping, was forced to conform to the actions of the rider—no matter how violent and painful those actions; after Caprilli, the rider conformed to the motions of the horse. Put simply (and simplicity was the heart of Caprilli’s system), the rider shortened his stirrups and leaned forward from the hips in order to go with the horse’s motion. This seems commonplace to us, but at the time it was revolutionary and controversial.

Some historical context is needed here. Before 1900, there was very little of what we would recognize as “horse sports.” For the most part, riding was literally a deadly business; the armies of the world all contained large units of mounted soldiers, trained and armed for lethal effect. Another large segment of the world’s horse population was devoted to agriculture and transport. Some precursors of what we now would recognize as horse sports appeared—for example, between roughly 1700 and 1800, the Enclosure Acts led to an increase in foxhunting in England. Foxes had been hunted from horseback with hounds since 1534, but the Enclosure Acts led to the fencing in of farms. (Under the previous “open field system,” agricultural land was unfenced; farmers worked strips of land scattered around their communities.) Enclosure created a need for jumping horses, as jumping the fences was necessary to keep up with hounds. We would certainly recognize hunting as horse sport, but some foxhunters don’t hunt to ride, they ride to hunt; horse sport as we know it was still very much in its infancy at this time.

To understand where the abuse began and persisted, we need to look at the cavalry of that era—whose men were also riding across country—and examine how they were taught to ride. One “expert,” the Earl of Pembroke, advised riders in 1762 to lean back and raise their hands when approaching an obstacle. One shudders to think of the awkward, unnatural efforts horses produced when subjected to this technique. It is even worse to consider that this backward system had been applied for centuries. As late as 1902, James Fillis was advising riders to hang on the reins upon landing, so as to support the horse in case his forelegs buckled. All of this is anathema to the modern horse world, and we should pause for a moment to consider the patient generosity of a creature that would continue to serve us, despite centuries of such mistreatment.

Caprilli and his theories changed all this, so it is little wonder I consider him such a transformative influence. Albert Einstein, equally a transformative influence in his own field, said, “The definition of genius is taking the complex and making it simple.” Yet another transformative man, Winston Churchill, said, “Out of intense complexities intense simplicities emerge.” Judged by those two statements, Caprilli certainly qualifies as a genius.

The essence of Caprilli’s genius, viewed in retrospect, was simplicity itself: The horse carries the weight of his rider more easily over his shoulders than over his loins, he uses his head and neck as a balancing lever, and his movements across country are more efficient when he is left in his natural balance. All this is simple—even obvious—to the modern reader, but getting the approval in the late 19th century of those who had been in charge of training cavalrymen and their horses for centuries was a complex process, one that took most of Caprilli’s short life.

Born in Livorno, Italy, in 1868, Caprilli entered the cavalry as a young man. He completed the year-long basic training offered at the Cavalry School of Pinerolo, during which he trained his horse, Sfacciato, along the lines of “il Sistema” that he was already developing. He went on to the more advanced six-month course at Tor di Quinto, another cavalry school, and there continued the studies that would consume the rest of his life.

When I started my detailed studies of Caprilli’s early career, I was immediately struck by how difficult it is for a historian to determine the truth about events that happened more than a century ago. For example, one of his biographers states that during his basic training Caprilli was a “less than moderate horseman,” while another states that he was a “brilliant horseman, who could ride horses beyond the abilities of his instructors.” Since “sfacciato” in Italian means insolent, cheeky, or impudent, I would vote for the latter description of Caprilli’s early riding skills. I will leave it to professional historians to argue about this; all I can say for certain is that he graduated successfully.

Great Spirits vs. Mediocre Minds

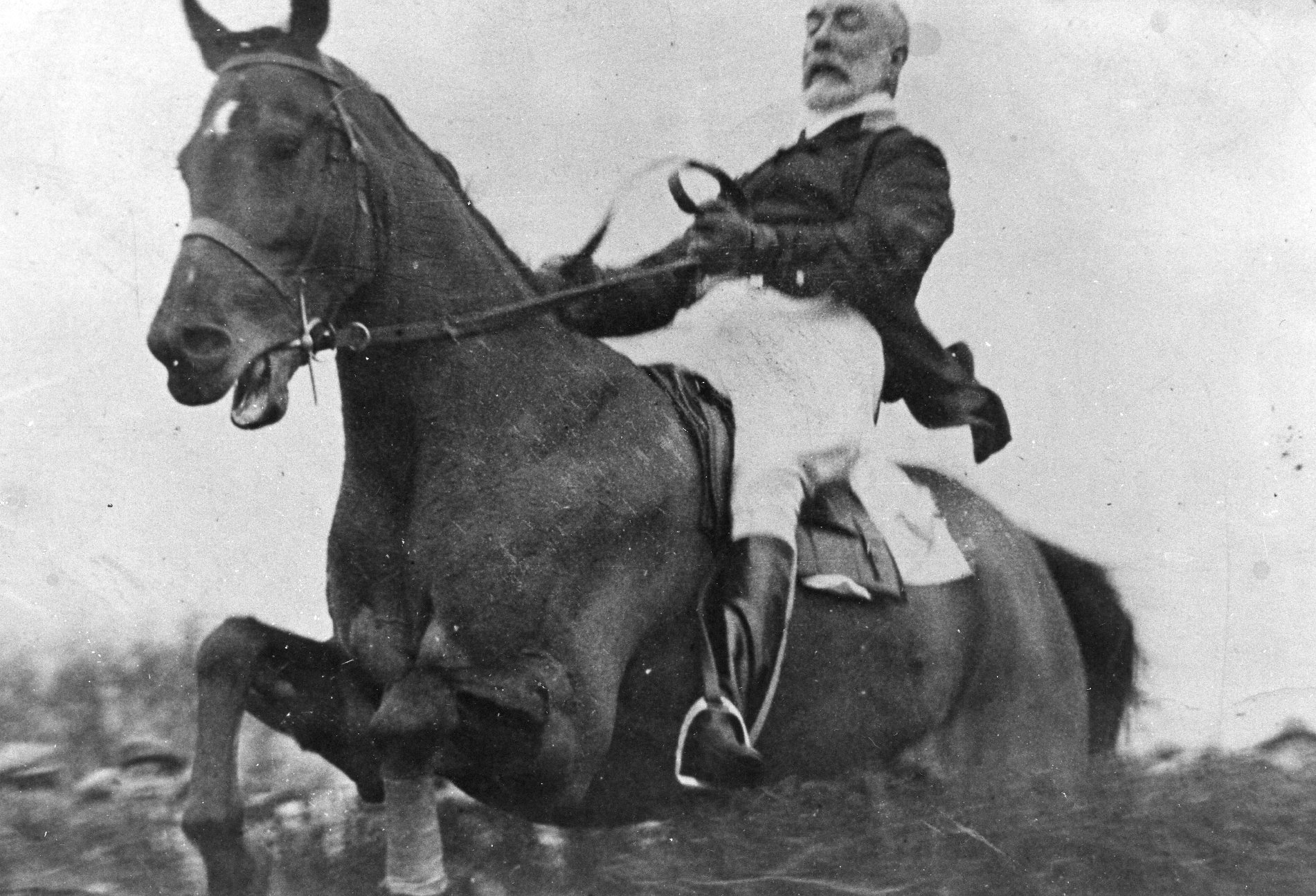

I have seen hundreds of photos of Caprilli taken throughout his life. At six feet tall, he was quite tall for his era, handsome and erect in his posture, long waisted, whip-thin and elegant in his cavalry uniform. In addition, those photos show him with a handle-bar mustache of spectacular dimensions. Perhaps these dismounted photos are a clue to the career-threatening difficulties that soon surrounded him. He had wasted no time stating that there was a better way to train horses and riders than the system in use when he started his career as a troop officer. Considering that he was a very junior officer who presumed to tell grizzled generals their business, trouble soon surfaced.

Einstein again: “Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.” Remember those photos I mentioned a moment ago? They were invariably either of Caprilli on horseback … or Caprilli in uniform at some social event, with what would have been described in less PC-conscious times as a “babe.” The ladies in question were usually referred to in the caption as a duchessa or contessa; Caprilli was obviously traveling in fast company. Although he was a talented rider and instructor, this fast company led to his speedy transfer to a cavalry post in the southern reaches of Italy, far from the temptations of Rome’s high society. This transfer was in the nature of being sent to Siberia, possibly in hope that it would cool off young Caprilli.

Far from the things that interested him most and with his military prospects on hold, life had lost its allure for Caprilli. However—call it chance, luck, divine intervention or mere coincidence—at this point things took a dramatic turn for the better. In 1896 H.R.H. The Count of Turin, General Inspector of the Cavalry and Commander of the Cavalry School at Pinerolo (near Turin), entered the scene. He reached out to Caprilli in exile and named him Chief Instructor at both Pinerolo and Tor di Quinto. This essentially put Caprilli in charge of training the Italian cavalry. Others noticed Caprilli’s impudence when discussing riding theory with senior officers, and were certainly dismayed by his familiarity with high society, but His Royal Highness saw the transformative genius that Caprilli brought to the world of horses.

Unintended Consequences

We need to remember that Caprilli did not set out to transform horse sports, but to transform the system of training soldiers to ride. His goal was to bring armed men and their horses into position more quickly and with less fatigue. This was no small consideration to military commanders, and his training principles were rapidly adopted by cavalries around the world.

Beginning in 1896, Caprilli used his position as the Italian cavalry’s chief instructor to implement his training principles. Unfortunately, he never wrote a book, and few of his writings survive. (One biographer states, “Caprilli had an antipathy to writing only second to his dislike of walking.”)

Piero Santini, his former student and amanuensis, compiled some of Caprilli’s articles and writings into The Caprilli Papers, published in 1967. This book was based on notes written by Caprilli in 1901 while confined to his bed with a serious injury … apparently one of many. Santini writes that Caprilli suffered “innumerable accidents that probably contributed to his early demise.” In late 1907, Caprilli was riding down the street on a borrowed horse when he was seen to sway in the saddle and fall, striking his head on a curbstone, never to recover. I am sure he would have wanted to die with his boots on, but this came far too soon. Ironically, Caprilli had astonished the horse world with his riding just a year earlier in a mounted display at the 1906 Olympics in Athens. He was just getting started when his life ended.

His death at age 39 left a huge gap in our understanding of his system. Foreign cavalries began to send their most talented instructors to Italy, in order to learn his new training methods, but they had to content themselves with second-hand information; Caprilli left no textbooks or written instructions. This presents us with one of the horse world’s greatest unanswered questions … where would his genius have led next?

As Caprilli’s sole aim was to improve the training of cavalry forces, it was an extremely fortunate unintended consequence that his system was so readily adapted to horse sports in general. When he died, he left behind a chasm between dressage and outdoor riding. His system was designed to manage large groups of men on horseback; the delicacy of control we associate with dressage was not his aim. We are left to wonder if he would have anticipated the synthesis of the two schools of thought, which did not truly merge until after 1950. His final comment on dressage was that “Manège [dressage] and cross-country equitation are, in my opinion, antagonistic; one excludes and destroys the other.”

A genius Caprilli was, but we now know that his vision was flawed. His system was sufficient for its intended purpose, but was not satisfactory for those seeking a closer partnership with horses and with the natural world. It was left to his students, and their students, to carry his system forward, continually refining and improving it. By the 1930s America’s greatest coach, rider and author, Col. Harry D. Chamberlin, was advocating a closer relationship between dressage and outdoor riding, and in the 1950s Bert de Némethy arrived from Hungary to continue the process. Today we are many degrees of separation from Caprilli; our instructors, who learned from now-distant students of Caprilli, are now improving the system in their turn.

We cannot know for sure where the development of horse sport will lead us. Modern riders are greatly in Caprilli’s debt, for they are the beneficiaries of his legacy. Yet even more important is his gift to horses: Every time a rider softens his hands in the air over a jump, the horse sighs with contentment and secretly gives thanks to the genius of Federico Caprilli.

Good Horsemanship Matters

An after-action report issued immediately after World War I mentioned that the British and American cavalry units were able to retain unit serviceability and cohesion longer than those of other countries.

The reason was that the American and British officers insisted that their units halt and dismount after 50 minutes in the saddle, remove their saddles, re-fold the woolen saddle blankets and then saddle up and remount— thus preventing saddle sores on the horses. Regardless of the endeavor, good horsemanship matters.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue of Practical Horseman.