The East Coast U.S. Dressage Federation Trainers Conference is hosted every year by Mary Anne McPhail at her High Meadow Farm in Loxahatchee, Florida. It feels like coming home for hundreds of trainers all over the U.S. as they converge not only to learn from the featured dressage trainer who is usually a guru from Europe but they also come to renew friendships. It’s a comfortable gathering that is always held on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and the following Tuesday. After two days of observing a top trainer teach, everyone has plenty of ideas to bring back to their home stables.

This year’s Trainers Conference was different because the official U.S. trainers took the stage this time, and they did not disappoint. George Williams, the U.S. Youth Coach, taught a Junior and a Young Rider each day; Christine Traurig, the U.S. Young Horse Coach, taught riders on two young horses each day. Charlotte Bredahl, the U.S. Developing Coach, taught two Prix St. Georges/Intermediaire horse-and-rider pairs, and Debbie McDonald, the U.S. Technical Advisor taught two Grand Prix combinations. Trainers in attendance got a clear understanding of our very own U.S. pipeline and the superb quality of training at each level. Below are training highlights from each trainer’s session.

George Williams

Williams brings a tremendous history of dressage theory into his teaching. With Junior rider Tori Belle, Williams explained 1) how the rider can assess the aids and 2) how to develop suppleness and balance.

1. Assessing the Rider’s Aids

A rider should always know where her horse’s legs are so she can ride in rhythm. The timing of the aids depends on the phase of the stride. For example, you can add weight to a hind leg- only when it is on the ground. That’s the rider’s responsibility, but the horse has a responsibility, too. The horse should respond to each of the aids separately.

You can assess the effectiveness of your aids in the warm up. Here’s how:

Leg and whip. The horse should have one of two responses to the leg and the whip: He should go forward or step away from the aid. The horse should stay relaxed when these forward aids are used.

The seat. Start in the rising trot. Then sit for three steps to see if your horse accepts your seat. How does he respond? Does he get tighter in his back or does he stay relaxed as he should? Rise again if he gets tense. Then test again by sitting for three strides. Does he go forward and come back from the seat? Work on that until he understands.

The hand. Check your horse’s response to the inner-rein aids. Can you flex your horse to the inside on a 20-meter circle? Then can you make him straight and flex him to the outside of the circle?

Check his responses to the outer-rein aids. Ask him to slow down with the outside hand by closing your fingers (without losing the flexion to the inside). Do it on the sitting moment when the inside hind leg is on the ground because that’s the moment when you can add weight to it. Think, now, now, now. When you apply the outside hand, does your horse stay in front of the inside leg? Each of these aids is an individual part of the half-halt, and you can work on the effectiveness of each part.

2. Develop Balance and Suppleness

Before adding power, riders must understand the importance of balance, suppleness, bending and using the corners to get that bend. Confirm that you can bend, turn and move the horse’s shoulders, which develop a supple, balanced horse with the following exercise.

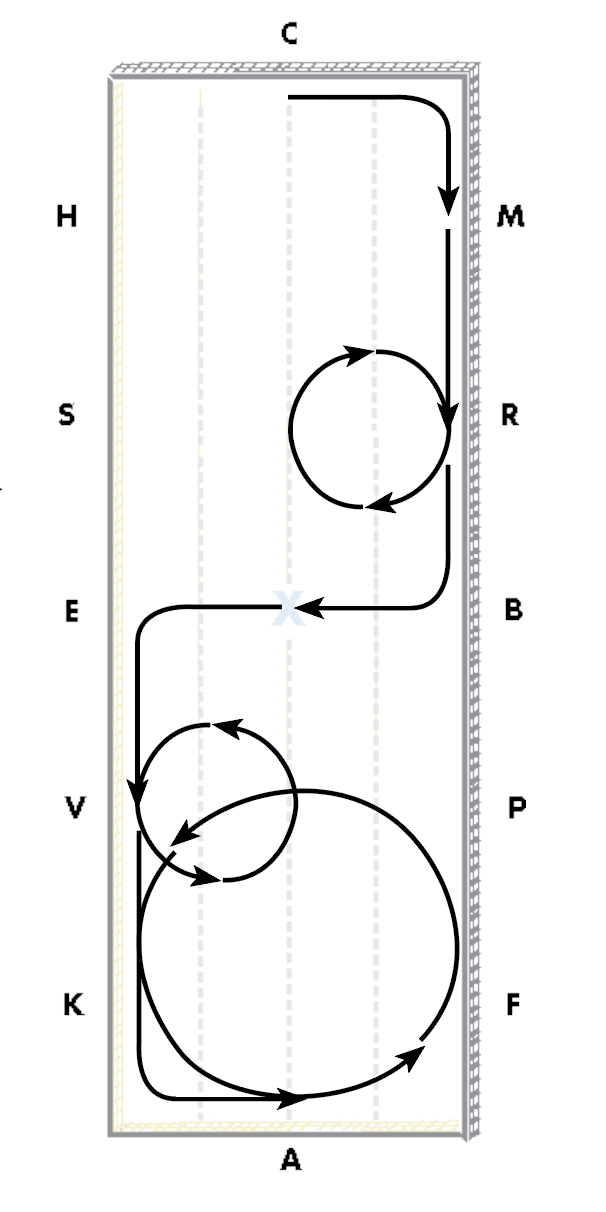

Try this: From C, track right in trot. At R, circle right 10 meters. At B, bend and turn right; straighten and then bend and turn left at E. At V, circle left 10 meters left. At A, circle 20 meters in a stretchy trot while rising. Repeat the exercise in both directions while always thinking forward. This exercise helps the rider mobilize the horse’s shoulders and improve his suppleness and balance.

Balance was also a priority as Williams instructed Sophia Schults, who represented youth doing the Young Rider tests. (The Young Rider Team test is the Prix St. Georges). The amount of collection asked in the Young Rider tests is much greater than at the Junior level. Williams explained and Schults demonstrated half-halt aids that improve the balance and increase collection. He asked, “Does the half-halt, in fact, affect the balance and bring the horse’s weight back?” The effectiveness of these balancing half-halt-aids is a crucial component to achieving collection.

To prepare, Williams asked riders to perform exercises with bending and turning, such as the one on page 83. Then he used the following exercises to focus on the transitions from one set of turning and bending aids to the other set of bending and turning aids, all of which improved the collection.

Try this: In this exercise, canter–trot–canter transitions improve the connection while 10-meter circles develop collection.

1. Canter on the left lead across the diagonal toward F

2. Trot before X

3. Do a 10-meter figure-eight left and right. Finish the diagonal in trot and canter at F.

4. Change directions and repeat.

And try this: As in the previous example, the transitions and small circles in this next exercise improve the collection by engaging the hindquarters naturally.

1. Track right in canter.

2. Ride a 10-meter circle at B.

3. Then when returning to B, transition to walk.

4. Repeat and do it in both directions.

Williams continued to challenge and improve both horses and riders with simple exercises and with an insistence on attention to the line of travel and clean transitions.

Christine Traurig

Traurig, like Williams, has an extraordinary background in theory and a remarkable ability to explain difficult concepts.

She spoke of the common vision of the U.S. coaches: While they’re always hoping to develop the next best horse in the world, they’re passionate about developing quality and excellence by putting the welfare of the horse first.

She focused on the importance of the young horse’s trust and confidence in his rider while, in this case, he was in a strange environment. The horses of both Michael Bragdell and Ali Potasky accepted the bit and trusted the rider’s hand.

Traurig described the aids:

The hand. The horse should follow the reins. For example, on a 20-meter circle, the rider’s inside rein indicates the flexion and direction. The degree of flexion (created with the inner wrist) needs to be the same as the degree of bend—not more—and the outside rein has to allow the flexion and let the inside rein create it. The outside rein then executes what the inside rein indicates. The horse’s shoulders follow what the inside rein indicates because the outside rein supports the direction and the outside leg supports the outside rein. The outside aids turn the horse.

The leg. Traurig’s “Holy Rule” was repeated frequently: “Around, up and in front of the inner leg.” The horse bends from the rider’s inside leg and goes into the outside rein in a way that the neck gets lower and longer, reaching forward toward the flexion. As the neck gets lower, the shoulders can lift. All parts of the body then become more supple.

Teach the horse the feeling of a circle and the process of bending, turning and riding ahead to the next circle point (imagine four points on the circle line to assist in accuracy). Every step on the circle needs to be the same.

Try this: From a 20-meter circle, reduce the size of the circle with the outside leg. Exercises with smaller circles “are not the staircase to the basement but rather the staircase to the attic,” Traurig said. She meant that smaller figures develop an uphill horse by putting the hindquarters in a position in which they naturally engage.

Keep in mind that all horses have hollow and stiff sides. Most of the time, the left side is stiff and the right side is hollow because the muscles are shorter on the right. On the stiffer side, the outside leg aid is very important so the horse doesn’t fall off the line of travel. On the hollow side, he will want to overbend, so think about making him straighter.

Traurig also discussed training concepts for the young horse. In the warm up, the rider should try to gain access to the horse’s topline and develop a swinging back. The horse’s neck is an extension of his back, and it’s important that the rider can control the position of the neck. The horse’s nose must reach forward and down. As he reaches through the neck to the bridle and relaxes throughout his topline, the back swings. The swinging back is evidence of suppleness, and if your horse is swinging in his back you will never have a rhythm mistake. Because rhythm and balance are so closely related, your horse won’t struggle with his balance, either.

Traurig explained that expression in the gaits shouldn’t happen until suppleness is cultivated. The horse’s hind legs can never develop more pushing or carrying power if he isn’t supple. Suppleness defines the quality of engagement, which is ultimately what adds to expression. In engagement, the horse’s hind legs are prepared to push and carry. When collection increases, the propulsion (pushing power) must stay available and vice versa.

Transitions from one gait to another improve the relaxation and suppleness, releasing the back and enabling the horse to engage.

Every transition forward and back cultivates the half-halts that balance and engage the horse. Likewise the half-halts improve the transitions. The half-halt is not about pulling, but it is a brief moment of boundary setting.

See also: More dressage training articles from Christine Traurig

Try this: Think not only of the exercise, but of the gymnastic effect that you want to achieve from the exercise.

1. Canter–trot–canter transitions. The energy has to stay in the horse. That is, he needs to retain the same balance, not falling left or right or on the forehand or losing impulsion. Also, each transition should be smooth and clear from working canter to working trot and vice versa. Repeat the transitions until they have achieved these qualities and then change directions.

2. Trot–walk–trot transitions. Transitions must be over the back and through the neck to the bit.

Pay special attention to the transition from trot to walk. You want the horse’s hind legs to engage in the downward transition. Repeat the transitions until the walk is balanced and rhythmic in the first step and the horse retains his balance and frame.

3. Leg-yield. The horse yields away from the leg and moves forward and sideways. The inside wrist loosens the jaw, and the horse’s inside hind leg swings forward and slightly sideways. The outside rein must allow the sideways movement but not allow the horse to fall through the shoulder. You can perform this exercise in rising trot.

4. Four-loop serpentine. This exercise supples the horse by turning and bending in both directions and it makes the horse more balanced.

Charlotte Bredahl

Bredahl supported the ideas of Williams and Traurig and added to the theme of focusing on quality. “Always make the work easy in the beginning and only make it harder as the work gets better. At no point do you want to go beyond the point in which the quality suffers,” she said. For example, with flying changes, never make counting the priority over quality—don’t stick with four-tempi changes if you horse has lost his straightness. Regain the straightness and then do another change. You need to always think of the quality. With an exercise such as pirouette or half-pass, is it easier to the right or the left? Start by going in the easier direction.

Even with the more developed Prix St. Georges horses, ridden by Jami Kment and Melissa Taylor, concentration was still on the basics. They did head-to-the-wall leg-yield in each direction to connect the horses from the inside leg to the outside rein. Bredahl wanted riders to feel the horses’ round backs and hind legs stepping toward the hand. From there, an elastic connection develops.

See also: Submission is the Goal at Every Level in Dressage

Bredahl also offered additional training insights:

• Prepare for canter with a slight shoulder-fore to get a smooth transition.

• To help horses who are croup high, use leg-yield in canter on a very slight angle and finish in shoulder-fore.

• Do a three-loop serpentine until the horse comes through his back in both directions, he reaches with commitment and can make the change of direction smoothly.

• Go back and forth between shoulder-in and half-pass. By doing this, you get more bend in the shoulder-in and more hind-leg reach in the half-pass. You want to keep the shoulder-in feeling in the half-pass. You can also go back and forth between leg-yield and shoulder-in to help the horse stay in front of each leg.

• If at any point the horse loses his forward attitude, refresh the gaits by going forward in a medium walk, trot or canter.

• If you lose engagement in the lateral work, half-halt and almost go to walk or do two steps of walk before resuming the lateral work. For example, do trot–walk–trot transitions in leg-yield or in half-pass.

• If your horse gets too strong in the hand, ride shoulder-in or even go to walk, and stay forward-thinking with your hands.

Debbie McDonald

McDonald furthered the collective training attitude as she helped Grand Prix riders Chris Hickey and Kerrigan Gluch. She used the word “play” often because she wants the horse to think the work is fun. And after each successful exercise, she said, “Give him a pat for that and walk,” or “Let him have a break for that.”

She reviewed the aids: The outside aids collect the horse and tell him how collected he should be. The inside aids keep him supple and bending. “Show him collection on the outside and suppleness with the inside,” she said.

One of the horses was hectic in the rhythm and tempo. “The way he is in his mouth, he is in his brain,” she commented, “and you can sometimes bring the horse to a very quiet place by slowing the tempo.” For this horse who wanted to run, she suggested the following exercises that helped the rider use the leg and seat aids:

• Play with leg-yield, focusing on the fact that you can change and control the tempo. Then go straight. The rider is in charge of the tempo.

• Make a square with quarter-turns and leg-yield out after each turn.

• Ride shoulder-in. Then go straight and feel a better trot.

• Play with transitions between haunches-fore and shoulder-in. Play with tempo changes within them.

At the Grand Prix level, the horse has to be responsible for keeping the balance and not relying on his rider’s hands. McDonald advised that the rider not use the hands for too long—half-halt and soften. But she said that it’s hard when the horse always wants to take over and run, even in the walk. In the walk, he can’t have any longer rein than the one with which he will stay connected with you. The rider doesn’t need to worry if the horse get too slow in the walk for now. As an aside, she said it is often the rider who chases the horse out of balance, although that was not the case with this session.

When it was time to work in canter, McDonald said that the rider needs to be particular that the horse initiates canter departs with a hind leg. Repeat the transitions to canter until they are good—you want the first stride to be as collected as possible. This transition is a predictor of the success of flying changes and pirouettes.

McDonald had a rider do working pirouettes and come out in shoulder-fore and then repeat in the other direction to keep the horse in front of the inside leg. In competition, the horse should collect no more than three strides before the pirouette, so he needs to be sharp to the aids to go forward and come back. If you want the horse more on the hind leg and more active, go out and let him stretch a little and then collect in the stretch.

After all the basic work, the Grand Prix work, including piaffe and passage, was very good with both horses. When schooling piaffe, McDonald advised that the riders do quarter-turns in piaffe “just so the horse feels like he’s going somewhere.”

After two days of watching the official U.S. trainers in action, the USDF trainers from every corner of this country had plenty of ideas to bring home to their respective stables. And that’s the point!

This article was originally published in the Spring 2019 issue of Practical Horseman.