By 1950, my family had been involved in horse sports for more than 30 years. Remember that Olympic equestrian sports were the realm of the military until 1952 when I tell you that my father, a U.S. Army officer, had ridden on the U.S. show-jumping team at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles and was non-riding reserve rider at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. (This connection would come full circle almost 50 years later at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, where I would be the non-riding reserve on our eventing team.)

But in 1950, my world turned over with some bad news: The U.S. Army had decided to “mechanize,” meaning there would be no more cavalry, no more horses, and no more Fort Riley (Kansas, where my father was posted) as the epicenter of horse sports. If tanks were the future of warfare, then horses had no place in the Army, and they were sold—just like that. The final auction was held at Fort Riley in 1953, and when the hammer dropped for the last time, there were still 73 horses unsold and declared surplus. Rather than see them humanely destroyed, my father and mother gave them a life tenancy at our family’s [neighboring] Rimrock Farm.

Courtesy, Jim Wofford

All the portees (trucks designed for horse transport) had already been sold, so the 73 horses were led by hand from Fort Riley … across the boundary between the military reservation and civilian life. Daddy must been having a mid-life crisis at that time; he had purchased a 1951 dark blue Ford convertible, and I was sitting on the back seat with the top down on that hot Kansas September morning. I remember that the men leading the horses were all senior non-commissioned officers with service stripes and ribbons on their shirts speaking of their long careers. Without fail, as each of them in the long line of horses and men quietly and patiently walking toward a new life crossed the boundary, they covered their eyes so the world would not see their tears shed at the end of an era. I didn’t understand it at the time. Later on, I joined them.

Those retired horses had a pretty good life. They lived out year-round, but they had shelters, running water, hay and sufficient acreage to graze over. The tall Kansas prairie grass cured on the stem in the fall and served as an additional source of hay for the herd. Vet students from the Kansas School of Veterinary Medicine came over to practice on these old-timers, and their hoof care was provided by Master Sgt. Charles Brown “Brownie,” who had forgotten more about shoeing horses than most will ever know. He had trimmed these horses’ feet before in other locations; one was London in 1948 when he was the farrier for the U.S. Army team at the Olympics.

Daddy inspected the retirees on a regular basis, and when one of our Army friends stopped by for the night, he would accompany Daddy on his rounds the next morning. Gen. John “Tupper” Cole was along one day, and as we drove across the pasture, he either identified various members of the herd or asked after the health of one who was not present. I took it for granted that these men would remember all the horses that had been in their care. My mother told me years later that when they were stationed at Fort Riley, she could always tell—and still remembered—the sound of Daddy’s footsteps on the sidewalk coming home from work. We don’t forget the people and things we love.

I have often been struck by the phenomenon of families who produce several generations of horsemen. I suppose part of it is that one is genetically predisposed to have an unusual affinity for animals. But a more important part might be the advantage one gains by growing up surrounded not just by horses, but by people who are unusually adept at training, riding, understanding and taking care of horses. I think there is a process of osmosis, where one absorbs horse knowledge without actively thinking about it. For someone born into that sort of environment, it is instinctive to know how horses react and how to relate with them. Growing up in a horse-crazy family is not an absolute necessity to a career with horses, but it helps. The fact that horses are not machines, but living, thinking, breathing creatures is second nature to me.

Icons at the Breakfast Table

As a result of “mechanization,” the U.S. Olympic Equestrian Team would no longer be military, and my father in 1951 became a founder and first president of the newly formed civilian U.S. Equestrian Team. In addition, he was the coach of the 1952 Olympic show-jumping and eventing teams. This is central to my story because Rimrock Farm became the training center for those teams as a result. I had grown up surrounded by horses until now, but this turn of events took the horses and riders surrounding me to a new level. It also explains why so many of the names on our various equestrian Halls of Fame are part of my life. I grew up with them around our table.

Courtesy, Jim Wofford

One of those icons who was at Rimrock Farm during the 1950s, Gen. Jonathan R. (Jack) Burton, loved to tell about coming down in the morning to our breakfast room, which had a glass-topped table capable of seating 10 people. He would sit down to his bacon and eggs, look through the glass, and there I would be, looking back up at him with my favorite Irish wolfhound, Lassie (spelled like the television program of the same name, but given the Scottish pronunciation, “Lossie.”). He said it almost put him off his eggs. Almost.

A few years later, my pony Tiny Blair and I did our first “combined test” (dressage and show jumping) at Fort Leavenworth. I didn’t know the test, so Jack got me through it by running around the dressage ring, yelling, “OK, Jimmie, now trot over here to me and walk when you get here.” Later that summer I went to my very first three-phase event at Percy Warner Park in Nashville, Tennessee, where I had the unusual distinction of getting eliminated in all three phases. I eventually got better; I just wish I hadn’t set the bar so low at first.

Several of our family friends had vivid memories of me as a small boy. Whitney Stone, one of the small group who founded the USET (and later my father’s successor as president), once wrote me that he remembered my biting him on the ankle as a very young child. He said the only thing that changed as I grew older was that his pain moved a little higher. If it didn’t happen that way, it should have.

Looking back, I realize mine was an unusual upbringing, but at the time it seemed perfectly natural. I mean, who didn’t pass the peanuts while my father and Bill Steinkraus were having another cocktail before dinner? I took all of this as normal, as I did the large, interconnected horse-world family that I was vaguely starting to be aware of and benefit from. In the years to come, this extended family would guide me at critical times and possibly even save my life. Its presence and influence will reappear throughout my story.

I’ll tell you about that in a minute, but first —what do I mean by “interconnected’? Consider this: My father graduated from West Point in 1920 and joined the cavalry. At that time, the entire U.S. Army had roughly 1,700 officers and 20,000 men. Given those numbers, it was probable that officers throughout the Army knew each other. Senior officers took an interest in young officers’ careers and made sure they had the sort of educational opportunities that would lead to high command. The Old Army took care of its own.

Jack Burton is a good example. Although he was a good rider, it was his performance in combat that brought him to the notice of senior officers. By the time I first knew him, Jack had already been wounded in two wars (World War II and Korea); he would later go on to be wounded in Vietnam while commanding the 1st AirCav division in combat. One of the most mild-mannered of men, Jack might have been overlooked in a civilian setting. However, the ability to lead other men in combat is a rare skill, and he found a home for his talents in the Army. By the time I knew him, Jack was the “aide” to Gen. I.D. White. A general’s aide is a combination of personal assistant, troubleshooter, dog robber (one who would steal from a dog in order to get the job done) and general officer-in-training. I have a soft spot in my heart for I.D. and his lovely wife, Judy, as they were my godparents. Like most cavalrymen, I.D. was horse crazy, which probably explains why our families were so close. He was chef d’équipe for the U.S. team at the 1948 London Olympics, so you know he understood horses and horsemanship.

Another aside: I.D. was a lifelong cavalryman and a brilliant combat commander, but he had a famous temper. When he heard that the Army was going to change the uniform lapel insignia and remove the historically significant “crossed sabers” that signified a cavalryman, he caught a plane for the Pentagon. (He had attained such an exalted rank by this time that he had his own plane.) Witnesses say that when he got there, two-star generals jumped out a window rather than face his considerable wrath at this insult to the generations of cavalrymen who had gone before him. Only about three men in the whole Army outranked him at this point in his career, and it took an ironclad promise from a superior officer to assuage him. The next time you see the branch insignia for armor, you will notice the crossed sabers around the insignia of a tank. This is in homage to the long line of cavalrymen, and their horses, who served us so bravely and honorably. We can thank I.D. for that. The point of all this reminiscence is that horses were at the heart of all of our family connections.

There was a lot for me to love, growing up at Rimrock Farm—horses, dogs, people, things to do—I had it going on. Then, like a thunderbolt out of the blue, I was incarcerated. There is no other word for it. I was put in jail, where I would remain for the next 19 years of my life … and I would gaze longingly out the window every day of my captivity. That’s the short story; the long story is that just short of my sixth birthday I was sent to Pleasant View School, to begin my education.

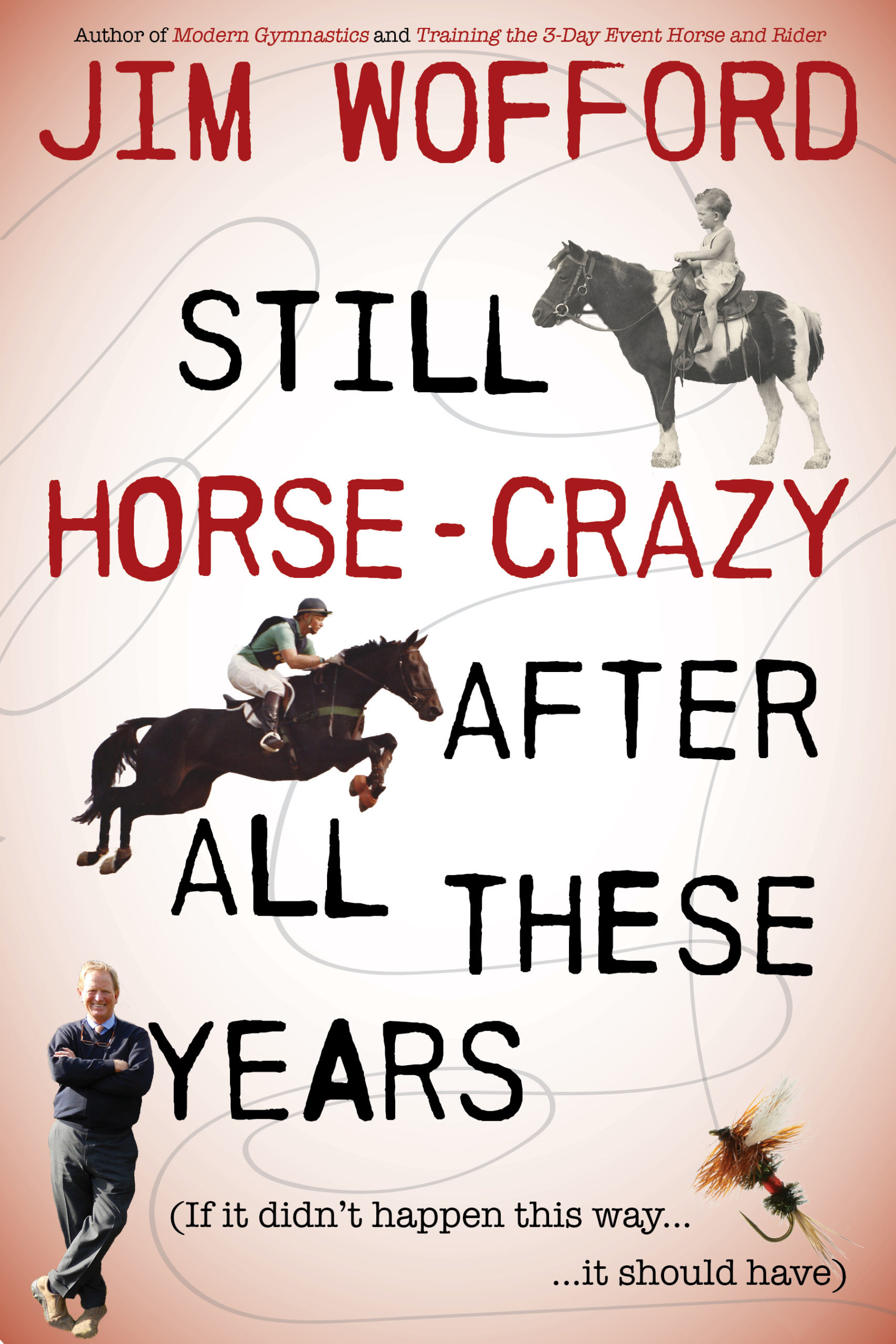

This month’s column is a prepublication excerpt from Jim Wofford’s forthcoming memoir Still Horse-Crazy After All These Years, scheduled to be published by Trafalgar Square Books in 2020. For more information, visit horseandriderbooks.com/product/STHOCR.html

This column originally appeared in the Spring 2020 issue.