If there is one thing horses will teach us, it is humility. Those of us who care deeply for horses are careful in our interactions with them—but we are human, and we make mistakes. Anyone who rides or trains horses has made mistakes—for example, asking our horse to maintain a higher frame than he is ready for, thus setting his training back. Even worse is a mistake that compromises our horse’s soundness, such as jumping on unsuitable footing.

Such mistakes haunt devoted horsemen, and the more experienced we become, the worse we feel about our blunders. After all, we are supposed to be experts now. By definition, don’t experts avoid mistakes? The answer is that of course experts make mistakes, and I can tell you from personal experience that making a mistake as an expert hurts … and keeps you awake at night. Mistakes certainly contribute to that humility I mentioned earlier.

My point here, however, is not to revisit my mistakes. It’s to continue to examine our training theories and practices in an effort to create the best possible partnership with our horses. My entire riding career has been guided by expert horsemen, men who wrote down their theories and set forth training practices for me to follow. Horsemen such as Vladimir Littauer and Gen. Harry D. Chamberlin have been my mentors, and their teachings have contributed directly to whatever competitive success I have achieved.

With that said and having just remarked on the humility required of riders and trainers, I hesitate to ask, “Is it possible they were wrong?”—but I feel I must.

Experts Aren’t Infallible

Experts should expect to be challenged, to have their teachings questioned and to defend their theories and practices. I am often asked to respond to questions about my own teachings, and I answer by citing Littauer and Chamberlin (among others) in reply. I add that in addition to my studies of great horsemen, I claim to be an expert because I have made more mistakes than most riders and have learned how to teach my students to avoid repeating those errors.

Disagreements and errors are part of the human condition and have been with us since Adam and Eve bought their first pony. (If you think arguments about drop nosebands get heated, wait until the argument about religion starts.) There were serious disagreements going on in England in the 1600s, with Oliver Cromwell in the middle of them. In 1650, he addressed the Scottish Presbyters (leaders of the Church of Scotland), saying, “I beseech you … think it possible you are mistaken.” Their refusal to think again did not turn out well for the Presbyters; Cromwell subsequently delivered a crushing defeat to their forces. It’s a good example of why we should be open to reconsidering our convictions.

This is as true for eventing, my discipline, as it was for the 17th-century Scottish Presbyters. For the past decade, the demands of eventing’s dressage phase have been heightened by increasing the collection requirements of the dressage test. Schooling a horse into collection is the pinnacle of dressage training, and its greater emphasis in the dressage phase of my sport caused a lot of consternation in the eventing community. Riding masters throughout the past several centuries have warned against collecting horses whose primary job was to gallop and jump. In his seminal 1733 work Ecole de Cavalerie, François Robichon de La Guérinière (who invented the shoulder-in among his many other accomplishments), warned against collected work for horses intended for outdoor riding. This concept has persisted so that more than 200 years later, riders of my generation were still taught to avoid collection when training our horses. Chamberlin advised against it, and both my Olympic coaches, Joe Lynch and Jack Le Goff, warned me against the practice on the grounds that horses who had been put into collection would lose their ability to gallop and jump efficiently.

Littauer, one of the outstanding horsemen of the mid-1900s, even wrote a series of magazine articles, which he self-published in a 1957 pamphlet titled Do Collected Gaits Have a Place in Schooling Hunters and Jumpers? Littauer emphatically believed they did not, saying, “For several reasons, collected gaits cannot be regarded as helpful for any type of riding where speed or jumping play an important role.”

And yet, today we see event horses perform admirable dressage tests where they receive high marks for collection and then successfully gallop and jump at high speed over large obstacles. There are many, me among them, who will explain why this is now the case … but we all avoid the demoralizing central conclusion about those who spoke out against the practice of collection for outdoor horses in the past: They were wrong. This is sobering, given that those opposed to collection were masters of equitation, men who had served as my examples throughout my career. Yet they were wrong, and we must admit it. Does this mean I should discard all of Chamberlin’s writings or ignore Littauer’s precepts? Of course not. My admiration for their works continues, but I now combine my belief in them with the knowledge that some of their teachings might be disproved by future generations.

Even the Great Chamberlin Got This Wrong

However, this realization does not give us license to experiment freely with our horses … an approach that usually does not end well. When the “rollkur” craze broke out in the dressage world, I spoke against it on both ethical and technical grounds. I felt that compelling our horses to adopt and maintain an unnatural head-and-neck position was contrary to the principles of classical equitation in which we do not ask our horses to do anything they do not present freely while in a state of nature. In addition, the overbent and compressed position that rollkur demanded was a position achieved by the pressure of the reins and not the pressure of the bit and thus was a flawed concept.

My experiences with recognizing Littauer’s mistaken thinking on collection and outdoor sports developed a sense of inquiry in me that might have been missing from my prior studies, and that sense has continued. When I reread all of Chamberlin’s works earlier this year, I noted his insistence on maintaining a forward seat, regardless of circumstance such as going down a steep slide.

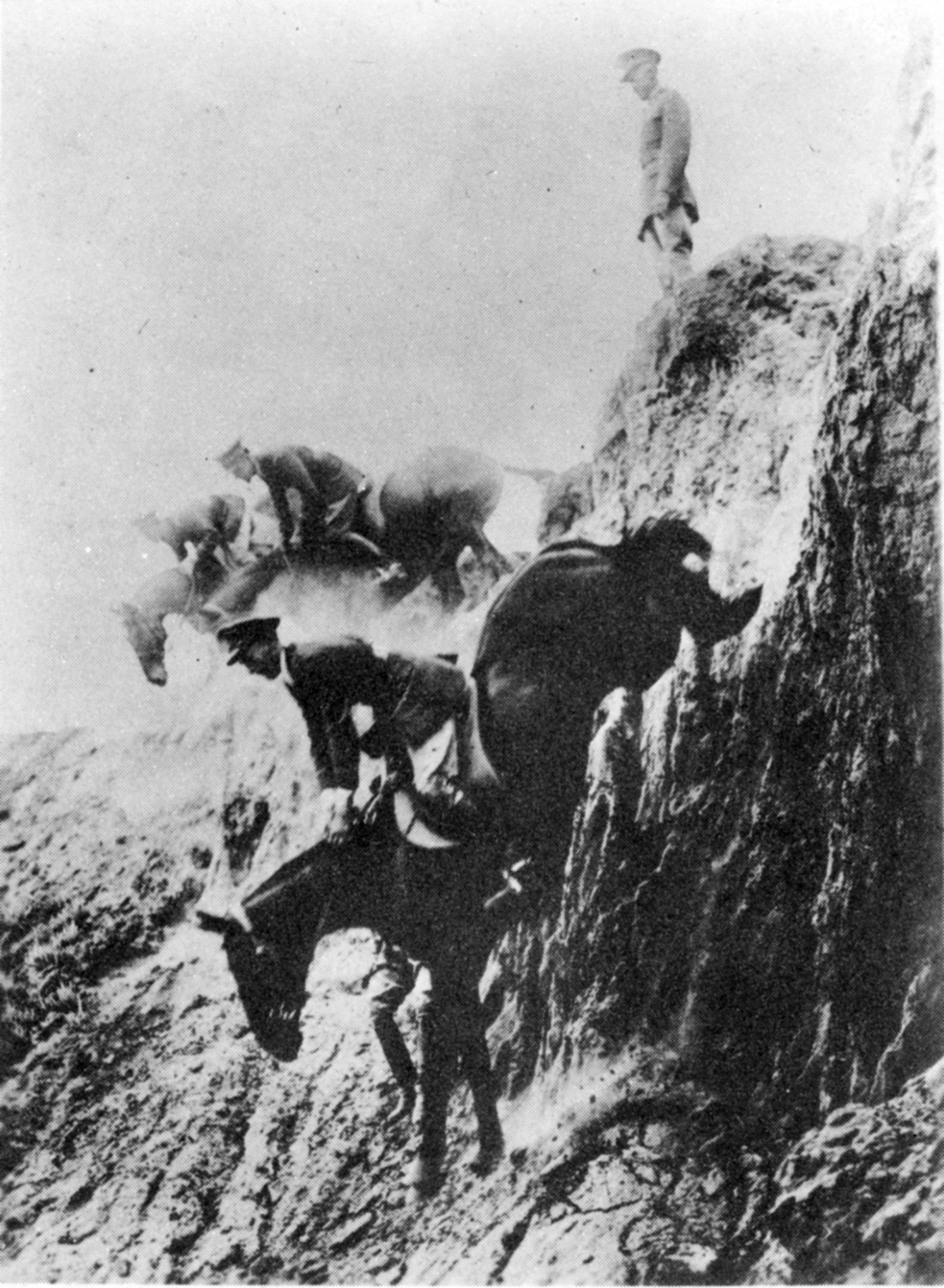

Most of us have seen pictures of cavalry officers going down “The Slide” at Breakneck Canyon in Fort Riley, Kansas. They are in a picture-perfect position with their lower legs at the girth, their bodies inclined forward and their hands quietly at the withers. In his writings, Chamberlin emphasizes that riders must keep their legs at the girth with the weight sinking deeply into their ankles and maintain the stability of their seats by the grip of their knees, calves and thighs. Their stirrup leathers are perpendicular to the ground even when the ground is not level.

However, this position is in direct contradiction to current everyday practices by our elite eventing riders, who sit dramatically behind the motion when jumping a large drop. Was Chamberlin right and our elite cross-country riders are wrong—or are our riders disproving Chamberlin’s theories by their success?

Actually, I think they are both wrong.

Vertical vs. Perpendicular: A Big Difference

Here’s my reasoning. While dressage is a seat-based position, the jumping and galloping position is stirrup-based. In effect, the stirrups are the ground for us. If we want to keep our balance, we need our feet underneath us, and that relationship changes as the situation changes. If you stand facing down a steep slope, you will instinctively have your feet in front of you; your balance will not be perpendicular to the ground. If you jog down that slope and then jump into the air, you will instinctively land with your feet in front of you. The same is true in reverse if you are facing up a steep slope. When we stand in balance, our relationship to the ground is not perpendicular but rather vertical to an imagined horizontal plane … perpendicular is relative, while vertical is an absolute.

If you want to keep your balance in the saddle, you must keep the ground (your stirrups) under you. I often hear instructors tell their students to keep their stirrup leathers vertical. This may be correct or may not—depending on the terrain. Certainly, in a level arena, it is entirely correct. If we are galloping and jumping uphill, however, our stirrup leathers should appear behind the girth, while when we’re galloping and jumping downhill, our stirrup leathers should be in front of the girth.

Ah … now you can see where I am going with this reasoning. I disagree with Chamberlin when he says that regardless of the terrain, riders must maintain a forward seat when jumping. In that position, the shock of landing over a downhill jump will cause riders to pivot around their knees, the shoulders will come in front of their knees and their heels will slip up and back. One can only hope that riders survive this sequence. My verbal shorthand is to tell my students, “Don’t lean forward to jump down.”

At the same time, I disagree with the position many riders adapt while jumping drops because it is awkward and many times unnecessarily burdens the horse’s back when it attempts to clear the obstacle with its hind legs. I do agree the riders’ legs should be in front of their bodies on the way down, but many event riders are sitting down, rather than sitting back, over drop fences. Landing over a drop with their seats on the saddle delivers a terrific shock to the riders’ and—much more importantly—the horses’ backs. The answer is simple—it’s just not easy: Riders need their stirrup leathers to be shorter than the length they are presently using. If they shorten their stirrups an inch, it will raise their seat bones an inch out of the saddle, and their horses will be able to clear the solid part of the obstacle more easily with their hind legs. Once riders raise their stirrups an inch, they can keep their feet in front of them, maintain the same angle behind their knees and absorb the shock of landing more efficiently.

Finding some particular aspect of past masters’ teachings to be, in my opinion, no longer correct has not caused me to lose confidence in their books and writings. Although I think those masters of equitation might be wrong in some specific instances, they are still masters, and I intend to continue to read their works and to apply their teachings. We owe that constant self-examination to our horses, who have given us so much … and so unquestioningly.

About Jim Wofford

Based at Fox Covert Farm in Upperville, Virginia, Jim Wofford competed in three Olympics and two World Championships and won the U.S. National Championship five times. He is also a highly respected coach. For more on Jim, go to jimwofford.blogspot.com.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of Practical Horseman.