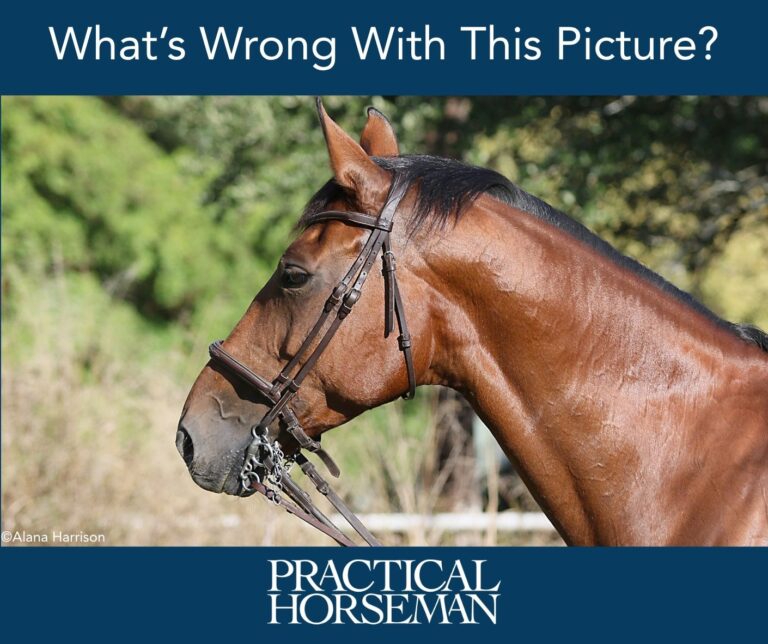

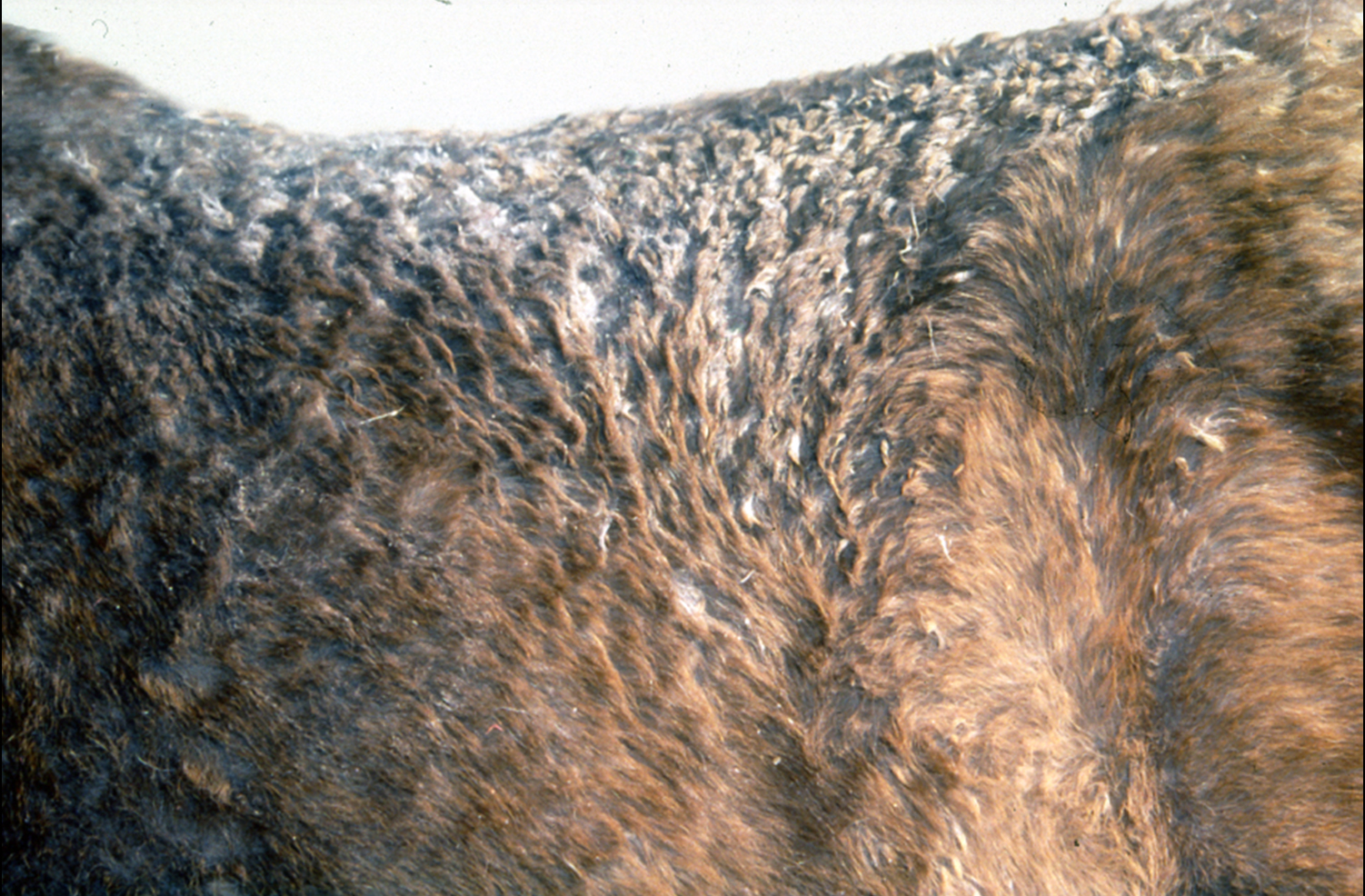

After a wet spring with frequent rain and the appearance of fiercely biting insects, you may notice your horse’s coat is not blooming quite as well as you would like. His skin is dry with loose, flaky hair, or worse, he’s been losing patches of hair when you groom him and the skin feels crusty when you run your hand over his back. These are signs of a common skin condition called dermatophilosis, often known as rain rot or rain scald.

Dermatophilosis is caused by the bacterium Dermatophilus congolensis, a microorganism found on the skin of a variety of mammals under normal circumstances but which can become aggravated when wet and cause infection, according to William Miller, VMD, DACVD, a veterinary dermatologist at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Highly contagious and potentially painful in extreme cases, this disease should be treated immediately but can be easily prevented through good grooming practices and attentive horse care.

What Is Rain Rot?

A horse who has been rained on or left to air-dry after a bath is not necessarily at risk for rain rot. But if his skin remains damp and bacteria find a way into his system via an open wound or an insect bite, infection can occur.

“Infection requires that the normal barriers of the skin be compromised. In an average horse, prolonged skin saturation without drying weakens the outermost layer of the skin, enabling easy infection,” Dr. Miller says. “With moisture, the organism becomes flagellated [capable of movement in the area of infection] and can spread on the animal’s body to new areas. When flagellated, the bacteria can also be transferred to another animal by insects or grooming tools.”

Rain rot is more common during wet seasons and in geographical locations with high precipitation and humidity, which foster the perfect environment for bacteria to grow. Minor cases appear as dry skin flakes and loose hair. Acute cases present as large matted clumps of hair and scabs that are tender to the touch and difficult to remove. A yellow to greenish pus may be visible around the scabs.

Rain rot is often found on the horse’s back and flanks and where moisture runs down the barrel, shoulders and face. Experienced professional groom and barn manager Max Corcoran notes that dermatophilosis can develop after horses have sweat under blankets or tack. She finds retired horses or those not in full work are more susceptible because they aren’t being groomed on a daily basis and they routinely have heavy winter coats where moisture can remain trapped for extended periods of time.

Horses with compromised immune systems are also at a higher risk. “If the horse has some underlying immunologic, metabolic or pre-existing skin disease, infection is easier and typically becomes more chronic and widespread,” Dr. Miller says. “Any disease that weakens the skin or immune system can predispose the horse to dermatophilosis if the organism is on the farm.”

Rain rot can be identified by looking at the affected area. “If the horse has a tender, crusting dermatitis of its topline that developed after some heavy rain and minimal sunlight to dry out the coat, the diagnosis is fairly straightforward and most veterinarians will go right to treatment,” Dr. Miller says.

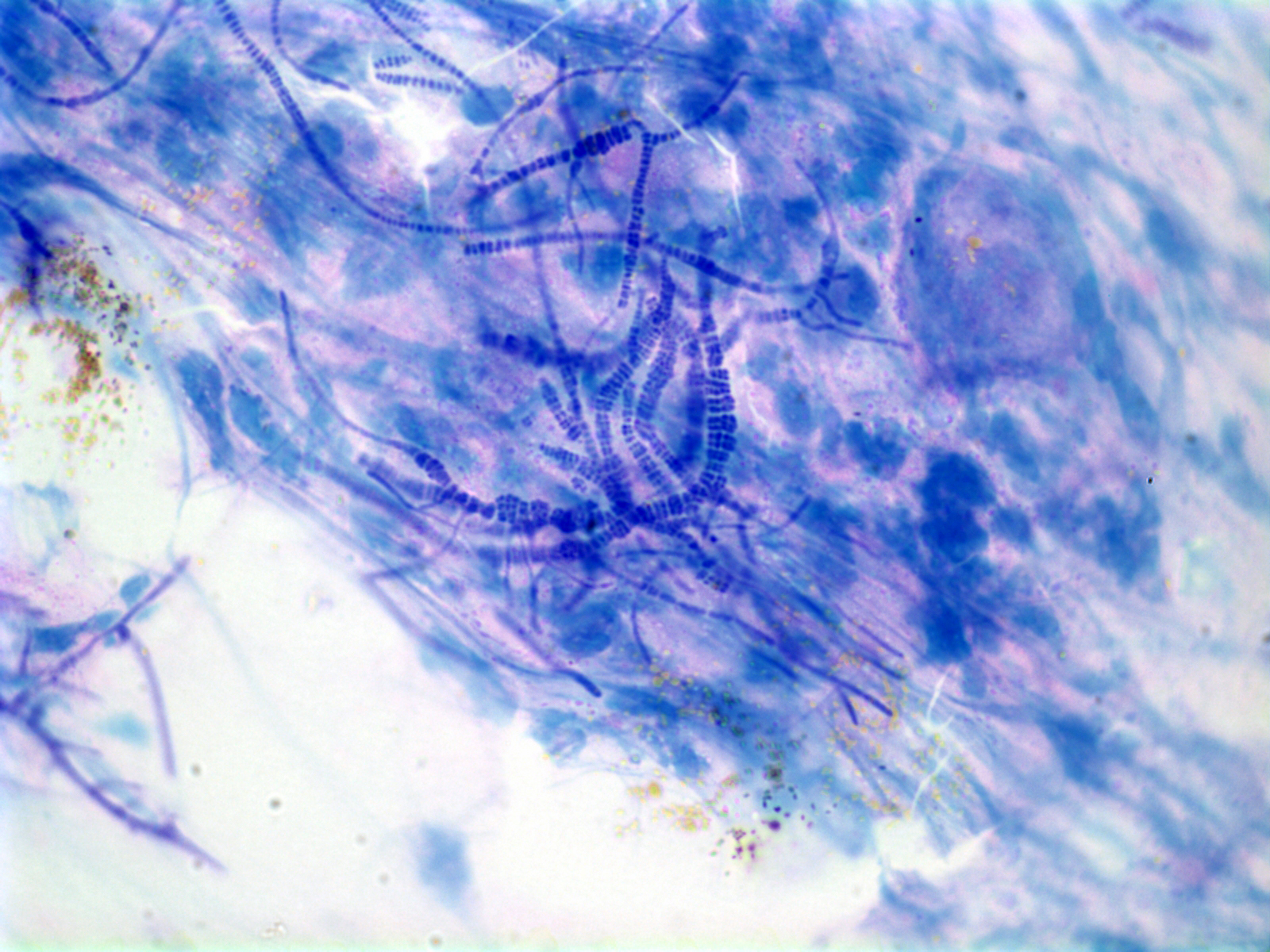

However, because horses can be affected by numerous bacterial and fungal skin conditions (see sidebar at left), a veterinarian can scientifically confirm dermatophilosis to eliminate any confusion about how to move forward with treatment. “It can be easy or hard to make the clinical diagnosis of dermatophilosis,” Dr. Miller says. “To absolutely prove the diagnosis, the organism has to be demonstrated by cytology of the pus, a bacterial culture or a skin biopsy.”

Treatment Options

If you suspect your horse has rain rot, call your veterinarian and together decide treatment based on the severity of his case.

The first step is to shield the affected area from exposure to moisture and allow oxygen to reach the skin. Remove wet sheets and blankets and let your horse dry before putting on dry ones.

If the only signs are dry, flaky skin and small scabs in clumps of loose hair, your veterinarian may recommend a thorough grooming to remove the scabbing followed by an antimicrobial bath to clean the area. This may be the only treatment necessary.

When the scabs are large and difficult to remove, in addition to grooming, you may need to pick large scabs off with a comb or your gloved fingers. This process will likely reveal sores and may cause bleeding. The lesions may be tender and could be painful for your horse depending on the severity of the condition, so be prepared for him to react when you pull the crusts away from the skin. Be sure to wear latex gloves because “the organism can infect humans through small cuts or other defects in the skin,” Dr. Miller cautions.

After the crusts are removed, a topical treatment may be used to kill the aggravated bacteria and heal the lesions. Dr. Miller explains that many antibacterial products are proven to be effective, especially those containing chlorhexidine, tamed iodine or lime sulfur. Some formulations can be found in your local tack store, but your vet may also prescribe a specific treatment.

Sometimes topical applications will not be enough to fully cure the condition. “In cases where the hair follicle becomes infected or the horse has chronic, widespread disease, systemic antibiotics most likely will be needed to supplement the topical treatments,” Dr. Miller says.

In cases where the scabs are large and difficult to remove, it may take several days of grooming, washing and treating to make progress.

Do not discard the removed crusts on the ground because they still harbor the contagious bacteria. Throw the crusts in the trash or burn them. “In acute dermatophilosis, the organism is on the surface of the skin, trapped within the crusts,” Dr. Miller says. “The removed crusts should be disposed of carefully to prevent contamination of the farm.”

While the horse recovers from rain rot, keep the affected area clean and closely monitor the lesions in case they become worse or healing is slow. Avoid covering the lesions with boots, wraps, saddle pads or other tack and equipment which could rub and reopen a wound or expose it to dirt and grime.

Because rain rot is contagious to humans and other animals, brushes, buckets and blankets that come in contact with an infected horse should be thoroughly cleaned after use and not shared with other horses. It’s also a good rule of thumb to keep an infected horse separated from other animals on the farm.

Mild cases of rain rot may resolve on their own with improved weather and good nutrition. However, acting with quick and aggressive treatment prevents unnecessary discomfort and stops the spread of the disease. If left untreated, a secondary infection could occur. “Wild animals, including wild horses, get clinical diseases and most will self-cure the disease when the rain stops, the sun comes out and the quality of the forage increases,” Dr. Miller says. “This will happen in a healthy owned horse, too, but the horse will be uncomfortable while waiting for self-cure and it will be a point source of infection for other animals on the farm.”

Prevention Is Better Than Cure

Max believes that when it comes to rain rot, the best source of treatment is prevention. As someone responsible for the care of both active competition horses as well as retirees, she says the key is regular grooming and a keen eye. “It goes back to basic horsemanship. Every horse should have a once-over every day to make sure there are no cuts, swelling or injuries. It’s vital to their well-being. If your horse has been standing in the rain for two days, make sure you check him for rain rot and get the mud off his legs.”

During the cold months, remove blankets every few days at least to check over a horse’s body and skin condition, Max advises. If possible, leave blankets off for a while so the skin can breathe. Check regularly to make sure your horse is not sweating under his blanket and remove it if he is damp.

“Every few days, the horses should get the minimum of a curry comb and a brush over their whole bodies, even the retired or pasture-boarded horses,” she continues. “You don’t have to bring them in and make them pretty, just get the dirt off. It’s a good time to make sure there is nothing there and break up the hairs so they don’t get matted and funky underneath.”

Do not blanket a horse who is still wet from a bath or has damp, sweaty hair after a workout. “Some people leave saddle-pad patches when they body clip, and I’ve seen horses sweat underneath it, and they just brush it quickly,” she says. Let even that small patch of hair dry completely before throwing on a sheet or blanket.

Besides regular grooming and careful attention to blanketing, there are other ways to help prevent rain rot. For horses who live outside 24/7 or do not get groomed regularly, a run-in shed or sturdy roofed structure will provide protection from the elements. Scraping off excess water after a bath will help their coats to dry more quickly. Insect repellant will lessen the urge to scratch and reduce the chance of bites and imperfections in the skin from giving bacteria a place to settle down and multiply.

If you suspect your horse has rain rot, identifying and treating it early is the key to avoiding discomfort and pain, hair loss or a secondary infection. Then work to prevent future incidents through good care, nutrition and regular grooming.

Bacterial vs. Fungal

Dermatophilosis is a bacterial disease that can sometimes be confused with fungal diseases and other skin conditions. Fungi are widespread in the environment but can cause illness if a fungus invades weakened or irritated skin, is inhaled or ingested.

Ringworm is a fungal dermatitis that thrives on keratin, the protein found in hair and skin cells. Ringworm typically presents as patches of crusty, dry skin combined with hair loss. The circular lesions can be itchy, but they may not appear to be inflamed or tender. Nevertheless, you should call your vet immediately if you believe your horse may have ringworm. It is highly contagious and can survive for long periods on different surfaces around the farm.

Use latex gloves when handling a horse with ringworm and take care to disinfect any grooming or riding equipment, feed tubs and water buckets that have been used by a horse with ringworm. Keep him isolated from other horses to prevent the disease from spreading.

Rain rot may also be difficult to discern from pastern dermatitis, commonly known as scratches or dew poisoning, which can be caused by fungi or bacteria. Horses in wet and muddy environments are usually more susceptible and those with white socks may be more sensitive to the condition. Scratches typically appears on the lower limbs, especially on the back of the pastern or fetlocks.

Scratches can be very painful for a horse as the area will become inflamed and scabby. The skin may appear cracked, and bleeding is possible. As a result, the leg may become swollen and hot, causing discomfort and potential lameness.

The open sores and scabbing that occur as a result of scratches create a port of entry for other bacteria, which can be a particular risk given the location on the horse’s lower leg. A horse suffering from scratches should be kept in a clean, dry stall or paddock until fully healed.

Max Corcoran explains that she is aggressive about treating horses with scratches, especially horses who are in full work or actively competing, because they may not be able to be exercised or wear boots due to inflammation in the leg and painful sores.

Because scratches is a multifactorial disease, the same treatment will not necessarily work every time. Consult your vet for the best treatment option for your horse.

While bacterial infections should be treated with antibacterial soaps and medication, fungal infections should be washed with antifungal solutions and treated with antifungal topical ointments. In all cases, the area should be kept clean, dry and exposed to air.

This article was originally published in the June 2017 issue of Practical Horseman.