It started with a subtle front-end lameness. You gave your horse a few days off, and the problem seemed to clear up. But it kept returning on and off, and now he travels with short, stabby strides even on good days. You often see him “pointing” a front foot—resting it with the heel cocked up off the ground. The lameness seems worse after his feet are trimmed and shod.

These clinical signs point to heel pain. They fit a pattern of foot pain previously known as navicular disease because it was thought that the cause was slow degeneration of the little navicular bone in the foot. But new technology—magnetic resonance imaging —has shattered that view. The navicular bone, it turns out, is just one of several structures that can produce these signs. Tendons and ligaments around it can be inflamed, and arthritis can develop in the joint between the several bones within the foot.

“MRI highlights the soft-tissue structures within the foot and can detect bone conditions that previously were undetectable with radiographs or ultrasound,” says Robin Dabareiner, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVS, associate professor of equine lameness and surgery at the Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine. As a result, “Treatment for horses with foot pain has changed dramatically,” she says. In this article, she helps explain how.

Many veterinarians now use the name “navicular disease” for cases in which they see degeneration of the navicular bone itself. The pattern of foot soreness that once went by that name is just called heel pain or pain in the caudal region (back third) of the foot until the exact structures causing the pain are identified. Whatever it’s called, heel pain can still limit or end a horse’s career. But with better diagnosis, more horses with this problem can be helped.

As an Amazon Associate, Practical Horseman may earn an affiliate commission when you buy through links on our site. Product links are selected by Practical Horseman editors.

Where Does It Hurt?

Heel pain nearly always appears in the front feet, Dr. Dabareiner says, although it can occur in the hind. Often both front feet are affected. The telltale signs include:

- Intermittent forelimb lameness. Sometimes the horse seems sound in the pasture but is clearly lame in work.

- Short, choppy strides. The horse’s feet land toe first, stabbing the ground, as he tries to keep weight off his heels.

- Pointing a front foot or shifting weight from one foot to the other when standing.

- Soreness to hoof testers over the back third of the foot.

The first step in figuring out what’s wrong is to confirm that the pain really is located in the heel. “That’s done with a nerve block, local anesthesia of the palmar digital nerves, which supply that part of the foot,” Dr. Dabareiner says. “If he’s sound when blocked, you’re only partway to a diagnosis because there are multiple structures in this region.”

These structures work together to support your horse and absorb shock when hoof meets ground. The coffin joint—the joint between the coffin bone, the small pastern bone above it and the navicular bone tucked in the back—is at the core. When the horse loads the foot, his weight comes down through the small pastern bone and disperses through the navicular bone to the heel and through the coffin bone to the toe. Cartilage cushions the bone surfaces where they meet, preventing friction between them. A fluid-filled joint capsule surrounds the joint.

Strong ligaments join the bones together. They include the collateral suspensory ligaments and impar ligament surrounding the navicular bone. The deep digital flexor tendon, which bends the limb, runs behind the navicular bone to attach to the bottom of the coffin bone. A fluid-filled pouch, the navicular bursa, helps cushion the bone from the pressure of the DDFT.

Sore heels may result from acute injuries or chronic problems in any of these structures. Sorting out exactly what’s wrong is challenging, especially because several things can be going on at once. The horse may have:

- Tendinitis: The DDFT comes under tremendous stress as the horse pushes off a front foot at speed or after landing from a jump. Strains and tears can occur in the tendon within the foot as well as higher in the leg.

- Strained ligaments: The ligaments that join the coffin joint and navicular bone together likewise undergo severe stress when the horse pushes off, makes sharp turns or lands on uneven ground. They also may be strained or torn, and they may heal incompletely after a tear and become chronically inflamed.

- Arthritis: Injuries and wear and tear can lead to inflammation in the coffin joint and navicular bursa. Inflammation produces pain and, over time, it can degrade the joint, leading to osteoarthritis.

- Navicular bursitis: The navicular bursa becomes inflamed, often along with problems in other structures. Sometimes adhesions develop between the bursa and the DDFT.

- True navicular disease: The navicular bone itself becomes inflamed and begins to degenerate. Although the cause is unclear, compression is a likely factor—the bone is squeezed with every step. Tension on the ligament that supports the bone is another likely cause. The bone responds to the irritation by remodeling—losing mineral content in some areas and developing calcium spurs in others.

“To treat the problem, you have to know what structure within the hoof capsule is causing the pain. The treatment depends on which structure is involved,” Dr. Dabareiner says. Diagnostic imaging will help your veterinarian see what’s going on.

Get The Picture

“If the horse stops limping after the palmar digital nerve block desensitizes the caudal half and bottom of the foot, the first step is to take X-rays,” Dr. Dabareiner says. “X-rays can tell you the condition of the navicular bone.” They’ll show if the bone has cavities or abnormal new bone growth, for example. But they may not give you a final answer. For one thing, navicular changes that show up on X-rays don’t always correlate to lameness. Many horses develop such changes with age or use but remain sound. And X-rays won’t reveal problems in any of the soft tissues. Bruising and edema (fluid) in the bone also don’t show up on X-rays.

If X-rays don’t yield a diagnosis, the ideal next step is MRI. Besides revealing soft-tissue problems that X-rays can’t find, MRI can give a more detailed picture of bone and joint surfaces. “MRI is really the only diagnostic modality that can positively identify a foot problem,” Dr. Dabareiner says. There are drawbacks, though.

Availability is one; equine MRI units are still few and far between. A number of major equine clinics have large MRI units with powerful magnets, which take the most detailed pictures. “The horse is put under gas anesthesia, and the legs are moved into the machine as far as the knee or hock,” Dr. Dabareiner says. “You can get both feet in, which is useful because we always image the corresponding foot as well as the sore one for comparison.”

There are also standing MRI units, including some mobile ones that travel to different equine clinics. They don’t require anesthesia, but they’re less powerful and produce images with lower resolution. “You can often get a diagnosis, but with less detail,” she says.

Cost is another drawback. The fee for an MRI scan with anesthesia ranges from $1,500 to more than $2,000, depending largely on where you live.

If MRI is out of reach geographically or financially, ultrasound imaging is a possibility. It is often used to image soft tissues in the leg and elsewhere, but it’s less helpful in the foot. “It’s difficult to get a clear ultrasound image in the hoof capsule. The scan can miss a lesion or artificially create one, and there are blind spots,” Dr. Dabareiner says. “One critical blind spot is the area where the DDFT runs behind the navicular bone. If there’s a lesion in the tendon there—and this is not uncommon—you won’t find it with ultrasound.”

For your bookshelf: Concise Guide to Navicular Syndrome in the Horse (Concise Guide series) For your bookshelf: The Essential Hoof Book: The Complete Modern Guide to Horse Feet – Anatomy, Care and Health, Disease Diagnosis and Treatment

Options to Target Treatment

It’s not unusual for diagnostic imaging to reveal multiple problems—inflamed ligaments along with changes to the navicular bone, say. The results will help your veterinarian target treatment for the best chance of success.

Shoeing: Treatment starts with good trimming and shoeing, regardless of what structures are involved. It’s important to keep the toes short to allow the foot to break over easily and the hoof trimmed at the horse’s natural angle so the bones of the foot are correctly aligned. Shoes that support the heels and ease breakover—bar shoes with rolled toes, for example—can help reduce stress and pressure on the back third of the foot. “Shoeing with a heel wedge reduces pressure on the heel by about 25 percent,” Dr. Dabareiner says.

Rest for tendons: A tendon or ligament injury will heal only with rest—a long period of rest, six months to a year. Tendons and ligaments heal slowly, and there’s no way to speed up the process. The horse should be in a stall or medical paddock so he won’t re-injure himself bucking and running, and ease back into work gradually. If this type of injury is causing your horse’s lameness, your veterinarian can help develop a program that fits his needs.

Arthritis and true navicular disease don’t heal with rest. Signs may improve, but they return when the horse goes back to work. Changes to the bone can’t be reversed so treatment focuses on managing the condition to slow its progression and keeping the horse as comfortable as possible.

Anti-inflammatory injections: “About half of problems that involve the bone respond to medication injected into the coffin joint,” Dr. Dabareiner says. “Of those that don’t, another 20 percent respond to injections in the navicular bursa.” The medications used are corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid or Adequan® (polysulfated glycosaminoglycan). The horse has a few days to a week off after the injection and then returns to work.

“You have to rule out acute soft-tissue problems before you inject,” Dr. Dabareiner cautions. “If the horse has a tear in the DDFT and you inject the joint or the bursa, he may feel better, but using the limb will make the tendon injury worse. One of the biggest advantages of MRI is that it can tell you if it’s OK to medicate and put the horse back into work.” Tendinitis is sometimes helped by an injection of anti-inflammatory medication into the tendon sheath (covering), but the horse still needs time to heal.

Injections aren’t a permanent fix; in most cases horses need to be medicated every three to six months, depending on the severity of the disease and the type of work the horse performs. “There are a limited number of times you can do this,” Dr. Dabareiner says. Over time, the medication may not help because the disease process has progressed.

Systemic meds: Several medications are used for problems that involve bone:

- Isoxsuprine is thought to increase blood supply to the foot, which could help maintain the tissues there. “It’s an oral drug and erratically absorbed,” Dr. Dabareiner says. Some horses absorb it and get high levels, some don’t and get none. “I think half or less are helped, so it’s falling out of favor. But there’s no harm in trying it.”

- Tildren® (tiludronate) is a human osteoporosis drug, a biophosphate that slows the process of bone remodeling. It has been used off-label in horses that have fluid and other clear signs of degeneration in the navicular bone. There are reports of success, but so far there’s limited scientific evidence to show how helpful it is. This drug is given intravenously.

- Oral phenylbutazone or another nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) may help short term, but soreness returns when the effects diminish. Most of these drugs have gastric and other side effects that rule out long-term use at high doses; however, some horses can be kept comfortable on low doses for a longer period of time. Newer NSAIDs such as firocoxib may have fewer side effects. Again, it’s important to be sure you’re not dealing with a soft-tissue injury before you put the horse back in work. If the horse competes, it’s also important to be sure that any medication he gets doesn’t violate your sport’s drug rules.

- Systemic joint protectants. Adequan® and hyaluaronic acid can be given once or twice a month in the muscle; these medications have both joint-repair and anti-inflammatory properties

Changes in work: A horse with arthritis or navicular changes—conditions that gradually worsen over time—may need a job change to stay comfortable. Jumping, galloping, hill work and work on hard or uneven surfaces tend to aggravate heel pain, but slow work on good ground can help by maintaining fitness in joints, ligaments and tendons. The horse’s comfort level should be your guide in deciding what works for him.

Surgery

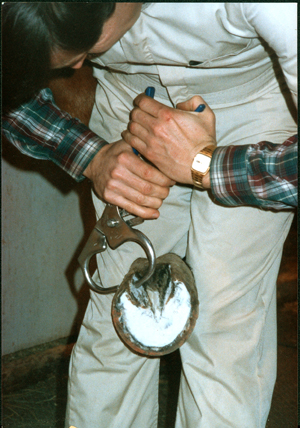

Nerving—a palmar digital neurectomy—is an option for horses that don’t respond to medical treatment. The surgeon cuts the palmar digital nerves to deaden feeling at the back of the foot. (The nerves can also be blocked with chemical agents.) The horse still has feeling in the front of the foot so he’s not likely to stumble more than he did before.

The procedure doesn’t fix anything; it’s done to keep the horse comfortable and extend his working life for a few years. It isn’t always successful. The horse may still be lame if the surgeon misses small nerve branches or if painful neuromas (small lumps of nerve tissue) form after surgery. There’s also a risk that injuries such as hoof punctures or bone fractures in the back third of the foot will go unnoticed because the horse doesn’t feel them. And in most cases, the nerves eventually regenerate and soreness returns.