It sounds like a dream arrangement: taking over an older, experienced grand-prix horse to ride in lower-level competitions, where he can soar over less-demanding fences. Showing one of these horses with mileage, however, means careful maintenance to keep him in top form without strain, since such mounts often have old injuries that could flare up if they are not cared for properly.

Philip Richter, a 41-year-old amateur rider, got the chance of a lifetime when he began riding the well-known grand-prix horse Glasgow, but their success came with meticulous attention to the animal’s welfare. In this article, Philip describes the transition, and along with Glasgow’s other caregivers, details the program they’ve followed to keep the horse healthy and happy.

Philip Richter will never forget the day in 1997 when show jumper Norman Dello Joio grabbed him for an urgent conversation behind one of the tents during the Festival of Champions competition at the US Equestrian Team headquarters in Gladstone, New Jersey.

“Norman looked at me with a combination of awe, excitement and desperation, telling me how he had to get Jamaica Jackpot, this horse that was in Scotland,” Philip recalled.

“You need to talk to your mom and your dad. We’ve got to put a syndicate together,” Norman had insisted.

“He knew the horse was extraordinary when he sat on it,” Philip said.

The syndicate assembled in a hurry included Philip’s mother, Judy Richter, Norman’s longtime supporter and mentor who was wowed when she saw a tape of the horse; her sister, Carol Hofmann Thompson, and grand-prix rider Lisa Tarnopol, as well as friends Tony Weight, Danny Magill, Ira Kapp and David Weisman. The large number of investors was necessary because of the cost of the horse, renamed Glasgow after the city in the ?region where Norman found him.

It never crossed Philip’s mind that eight years later, in 2005, he would be the one riding the regal Dutch-bred chestnut gelding. After a successful career at the highest level of the sport, Norman decided it was time for Glasgow to stop jumping in grands prix, but that it wasn’t time for him to stop jumping entirely.

At 15, the horse “needed some aspirin and medication to feel his best,” said Norman. “To this day, he has all the heart in the world, and he’s a fantastic show horse. I thought with Judy Richter being such a knowledgeable horsewoman, she could give him the care he needed and let him show in a limited way and still have a fantastic life.

“My gut was if we just retired him and turned him out, he would fall apart pretty quickly physically. The horse really loves jumping and competing, so I thought this would be the best solution.”

So Norman told Philip he wanted him to ride the horse in the Amateur-Owner Jumpers, where the fences ranged up to 1.4 meters (4-foot-6) with 1.45-meter spreads, as opposed to the top height of 1.6 meters (5-foot-3) and width of 2 meters (more for water jumps and triple bars) in grand-prix championships.

The syndicate that owned Glasgow wanted what was best for him, and Norman noted he would get the finest care after Philip took over the reins.

The investors were well aware of Glasgow’s veterinary needs, although much of the cost of keeping and campaigning him had been covered by his considerable winnings.

“I think nobody would have felt good selling him to some random amateur to show who wouldn’t have known his particulars and gone the extra mile to make sure he got the best care,” said Philip.

Winning the Lottery with Conditions

An accomplished Amateur-Owner Jumper competitor, Philip had a predictable first reaction to the idea of showing Glasgow: “I just won the lottery.”

But taking over a big-name horse has its downside. Everyone remembers the heyday of such an animal. It’s a lot to live up to.

After thinking about it, Philip was more reserved. “I was a little bit nervous,” he acknowledged.

Glasgow, now 20, definitely enjoyed quite a reputation. What if the horse didn’t perform well for Philip? It would be a blot on the name of an animal who was once one of the world’s best jumpers.

“As an amateur, I can get on and make a lot of mistakes,” Philip observed.

On the other hand, if they did well, it would be what everyone expected. After Philip and Glasgow finished their victory gallop in the prestigious Saturday Amateur-Owner Jumper Classic in Lake Placid, New York, last year, someone at ringside asked, “How can you not win on Glasgow?”

The comment smarted for a minute, but Philip conceded, “It’s a true statement, really. The horse could jump the High Amateurs with one leg tied up around his ear.”

That said, however, “Glasgow’s not an easy horse to ride. He sights in at jumps and is really aggressive to them. He’s a handful,” Philip said.

In addition, Philip faces the added challenge many amateurs do—limited riding time. As a partner and a managing director of Hollow Brook Associates LLC, a New York City-based registered investment adviser, he often just gets in the saddle at shows and does only a few of those a year. He concentrates on the most competitive fixtures, such as the Devon Horse Show in Pennsylvania, the Hampton Classic in New York and the Old Salem Farm Horse Show in New York.

The beginning of the relationship between Philip and Glasgow “was the crucial time. I think we got along really well from the start,” said Philip. One reason is that Philip is comfortable riding a hot horse like Glasgow; another is the horse was “incredibly well-broke and responsive.” And, as Judy pointed out, “Norman made it all work: Norman, [Norman’s son] Nick and sometimes [Norman’s assistant] Sean Crooks school the horse and get him ready. You don’t just take good care of him and walk in the ring at Lake Placid and win.”

But there was still a lot for Philip to figure out with the horse. “I’ve learned to let him go and let him tell me what he can and can’t do. It’s a matter of trusting him and leading him to the jumps, not telling him to go to the jumps,” he said.

Occasionally Philip has found that to be too much of a good thing. “One year at Lake Placid, the last line on the course was eight strides; then in the second round, a flying seven strides.” Or so it seemed.

“I gave him the reins and was clear. I wound up doing it in the six, not the seven. I landed and saw the distance.” Philip said. “You can get away with things on a horse like that, which you can’t get away with on a lesser horse. That’s well and good, but you have to be respectful.”

Tip-Top Care

In addition to learning how to ride such a talented horse, Philip knew they’d need a plan to keep Glasgow healthy and sound. Moving a veteran show horse down into a lower division is a great form of recycling, but older horses often come with injuries or conditions that require careful upkeep.

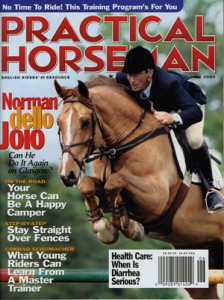

Glasgow and Norman Dello Joio were featured on Practical Horseman’s June 2000 cover.

Glasgow and Norman Dello Joio were featured on Practical Horseman’s June 2000 cover.As Allen Schoen, DVM, who specializes in integrative therapy, noted, it takes a village to keep Glasgow in tip-top form. John Steele, DVM, is the horse’s primary care veterinarian, with decades of experience at his disposal. Sarah Carrs, Glasgow’s groom, generally hacks him between shows. Meanwhile, the Richters’ barn manager, Geralyn Campbell, keeps a watchful eye on the overall picture.

“I think there are a lot of horses out there that could have a great life if they were maintained right and not overshown,” said Philip, who has four older horses, all of whom have had challenges.

“We’ve been able to navigate those issues and be very happy. There’s no reason these horses can’t show into their late teens or early 20s,” continued Philip, who competed on another of his horses, Chekhov, until he was 24.

Dr. Steele said the elements for success in keeping older horses going after they drop down to a less-demanding division involve “a fitness program so they don’t get soft (‘rest and you rust; motion is lotion’) and a farrier who keeps them shod in a proper manner—a good foot under them takes them a long way.”

He added, “One thing I feel strongly about in these older horses is periodic injections of Adequan [polysulfated glycosaminoglycan, an intramuscular joint treatment]. I think it’s very important to them, it helps save the joints, it helps promote good synovial fluid in their joints.”

If possible, he likes to see the older horses spend a couple of months without shoes. “Let them wear the feet the way they want. But that means a little time off and not pushing them.”

He suggests really knowing your horse.

“The person on the ground who’s lived with him will tell you a lot of things you may or may not perceive. You don’t jump at putting a lot of unnatural stuff on them; try to be as natural and normal as possible; keep them at the level where you’re not doing a lot medicinally with these horses to keep them going, and a lot of them just go on and do their job nicely.”

It’s important that the transition to the lower level, a new rider and a new home is done properly.

In the case of Glasgow, it helped that Norman had a long association with the Richters. While Glasgow spent most of his time at Norman’s Florida farm or on the road at shows in Canada and Europe, he occasionally would stay at the Richters’ Coker Farm in Bedford, New York, the heart of Westchester County’s horse country.

So making that his permanent headquarters wasn’t difficult, the way it could have been for another horse going to a new home and a new rider, where he might need more time to adjust to his new surroundings and routine.

As is befitting for a horse of Glasgow’s stature, he gets meticulous attention.

When Glasgow arrived at Coker, Dr. Schoen felt he was uptight and anxious. The combination of acupuncture and chiropractic work, which Dr. Schoen prefers to call musculoskeletal alignment, relaxed Glasgow and relieved repetitive stress.

“With the repetitive stress injuries, they start developing repetitive patterns in their musculoskeletal system: knots and trigger points, vertebrae start being compressed from tightness in ligaments and tendons,” said Dr. Schoen.

Getting them back into alignment, he said, relieves pressure and enables them to move more freely with lesser restrictions.

“In Chinese medicine, any pain is considered a lack of flow, a lack of movement. So I try to relieve pain and suffering by improving the mobility and the movement. One needs to address not just the joints, but the muscles, tendons and ligaments all around it.”

Glasgow settled into a routine that worked for him in his new life. He is shod regularly by Mike Boyland. “He is a genius and a big part of why Glasgow has stayed sound,” Philip said.

His feed of choice is Respond, a beet-pulp mix with some sweet feed in it; he gets three quarts twice a day. He also has free choice timothy or grass hay.

He’s ridden early in the day six days a week, a low-pressure hack around Coker’s 100 acres. Then there are the daily 52-minute workouts on a “horse gym,” a treadmill where the speed and angle can be adjusted while the footing is consistent.

Philip believes older horses need to stay fit at home while not being shown that often. At the shows, the schedule is judicious.

“As Glasgow has aged, we try to do one speed class during the week and then just roll him out for the classics,” said Philip.

Glasgow also gets time to be a horse. He’s turned out for 2-1/2 hours in Coker Farm’s grand-prix field if the weather is good.

Bathing is important when Glasgow is working because he’s allergic to his own sweat on his face, according to Sarah. If it isn’t washed off, he’ll lose hair and look like he suffered a mild sunburn. At shows, he gets a Vetrolin bath and his legs are iced each time he jumps. Sarah uses what Philip calls “old school” black Velcro ice boots loaded with crushed ice, which can be pulled tight across the cannon bone for a good fit. Poultice is applied afterward.

He wears a Back on Track Therapeutic Mesh Sheet, made of breathable mesh with fabric containing polyester thread embedded with a fine ceramic powder that is designed to reflect the horse’s own body warmth and can help alleviate pain associated with inflamed muscles and joints.

Footing is also key with an older horse, noted Philip, saying, “It’s no coincidence that we primarily show at Old Salem, Lake Placid and the Hamptons, all on grass. If there is rain or it’s at all slippery, we just scratch.”

While modern all-weather footing can be great, it has to be managed properly, he pointed out, because sometimes it can get very flat and dead, stinging older tendons.

And if an older horse does get injured, giving him the time off to recuperate is critical. Despite all the care, Glasgow sustained a minute tendon tear on his right front leg at the Hampton Classic in September. It showed up on a post-show scan, so plans called for him to skip the Florida circuit and come out in May at the Old Salem Farm Horse Show.

The tear “healed really quickly,” Philip said, noting “he’s totally fine on the treadmill and being ridden daily. [While Sarah’s in Florida, he’s ridden by America’s last (1987) World Cup Finals champion, Katherine Burdsall Heller, who lives nearby.] We almost thought about taking him to Florida.”

But Philip has two other horses there, and with work commitments and involvement with a new interest, reining, his plate is full enough for the winter.

Glasgow eventually will retire at Coker, where there is already an established program from pensioners such as Gaelic, the 33-year-old jumper, formerly ridden by Andre Dignelli, and Grappa and Hurricane, who belong to Philip’s fiancee and reining enthusiast, Sarah Willeman.

The retirees also have a routine involving the horse gym and exercise. “These horses can’t just go off the cliff and do nothing,” Philip pointed out.

He thinks Glasgow still has the desire to jump and compete, however, and his team of caregivers will continue to go the extra mile to make sure he’s happy and healthy to do so for as long as he wants.

This article originally appeared in the March 2012 issue of Practical Horseman magazine.