Does your horse do any of the following?

- Have trouble holding his head straight when ridden

- Have difficulty bending to the left or right

- Chew on the bit or excessively or turn his head when consuming grain

- Eat slowly or drop a lot of hay out of his mouth when eating

- Act head shy or resist when receiving oral deworming paste

These and many other behaviors could be signs that your horse is in need of dental care from a qualified and experienced professional.

As an equine veterinarian who focuses only on dentistry, I have found there is a lot more to dentistry than just grinding off the sharp enamel points. In this article, I will describe the common problems that many horses develop within their mouths and how these issues affect their ability to chew and to remain comfortable while being ridden. Proper care can improve their quality of life and extend the lifespan of their teeth. The underlying causes of many of the conditions discussed are complex and, in some cases, still not completely understood by the veterinary community, although we’re hoping that ongoing research will shed some light on the issues.

Anatomy Review

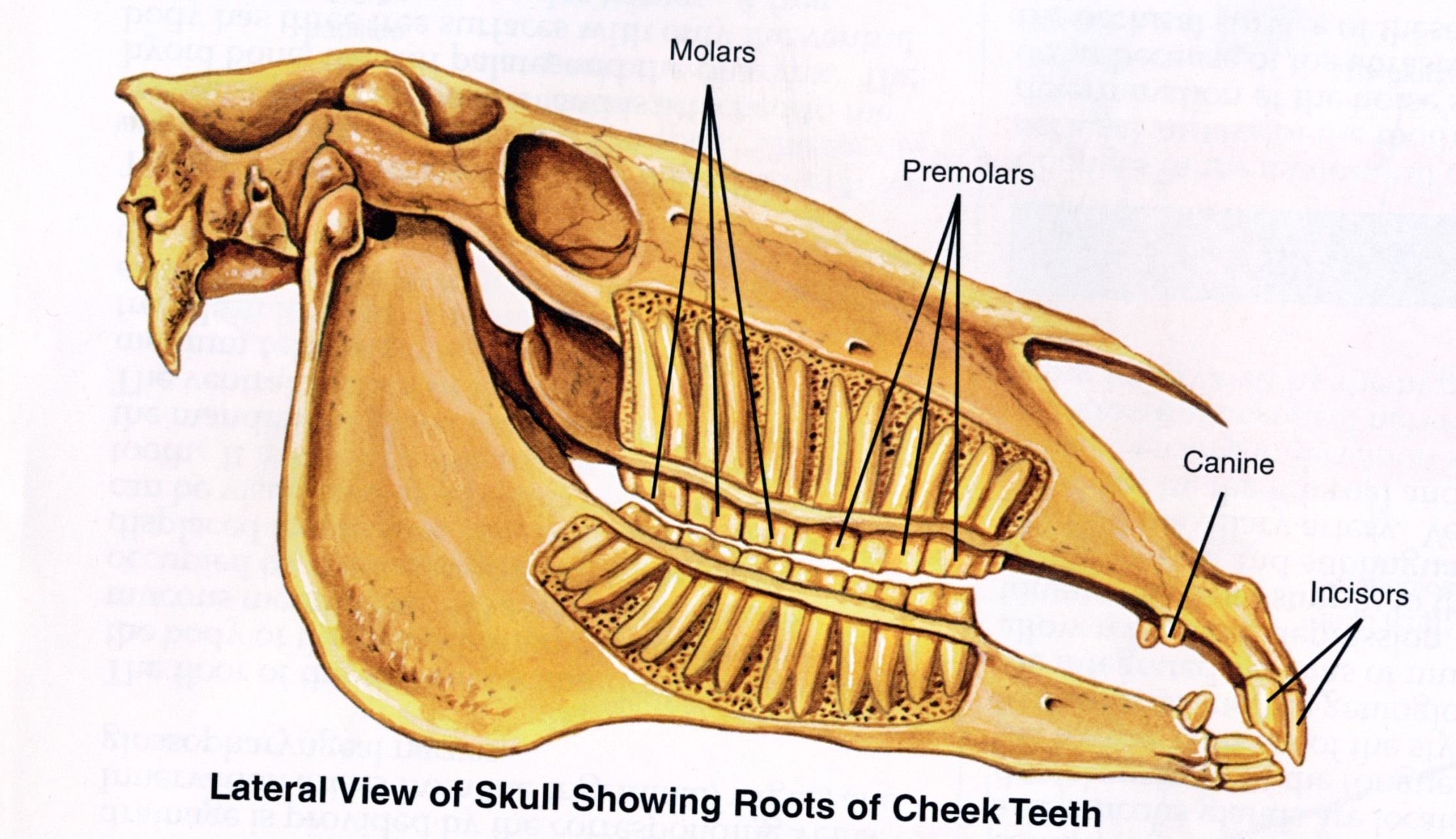

To have a better idea of the types of dental problems that can arise, it’s helpful to have a basic knowledge of the anatomy of the horse’s mouth. An adult horse can have as many as 44 teeth, depending on the individual. Males typically have only 40, while females generally have only 36 because they tend not to develop the four large canine teeth that the bit rests near.

Horses have 12 incisor teeth—six upper and six lower—which are used primarily to grasp forage and grain, transferring them to the tongue and then onto the cheek teeth. There are a total of 24 cheek teeth, with six upper teeth and six lower teeth on each side of the head, whose main function is chewing. The cheek teeth consist of three premolars and three molars in each row, also called an arcade. The most efficient chewing motion for the horse that will promote balance, comfort and appropriate wearing of the teeth is a side-to-side motion with both the left and right sides of the mouth being used equally. Horses are able to chew on only one side of their mouth at a time. When horses chew on the left side of their mouth, for example, the cheek teeth on the right are quite far from touching. Over the first 20–30 years of a horse’s life, his incisors and cheek teeth are almost always continuously erupting and grinding against one another.

Sharp Enamel Points

The most commonly addressed issue in a horse’s mouth is sharp enamel points on the premolars and molars. On the upper teeth, they are located on the side of the teeth nearest the cheek and on the lower teeth, they’re on the side of the teeth nearest the tongue. When sharp enough, these points can result in trauma to the tissues of the mouth, commonly called ulceration. The process of floating teeth is the act of using a grinding tool to smooth off these points. In my experience, horses tend to demonstrate specific behaviors while chewing and being ridden when they have these sharp points, such as:

- Turning their heads sideways or opening and stretching their mouths when eating

- Demonstrating some degree of resistance to the bit, especially with a tight noseband

- Flipping their heads or excessively chewing on the bit

Effects of Imbalance

Although sharp enamel points are usually the most common issue horse owners are concerned about, they are not the most important aspect of equine dentistry. The chewing surface of the cheek teeth of horses should be balanced so they are relatively level from the first tooth in the row to the last. This allows the arcades of the cheek teeth to function properly, lets the horse chew comfortably and efficiently and promotes appropriate wearing of the teeth. Imbalance, or the loss of that level surface, of the arcades of cheek teeth usually results from a number of abnormalities.

Abnormally formed teeth, misaligned teeth and many other issues will dictate how the upper and lower teeth grind upon each other, potentially resulting in overgrown areas along the rows of cheek teeth. These overgrown areas, commonly referred to as ridges, ramps, hooks, waves or steps (depending on the location and type of issue), can restrict chewing motion, develop gaps between teeth with feed-packing and cause fractured teeth, prematurely worn teeth and many other health and comfort risks. A small imbalance on the cheek teeth can turn into a significant issue within just a few months, especially in a younger horse. This is one of the main reasons that a yearly or biannually dental examination with attention to the causes of these imbalances is so vital.

Types of Imbalance

There are many types of damaging imbalances that can occur in a horse’s mouth, most of which result from overgrown areas due to an issue that can be corrected by timely, appropriate dental care.

- Hook: An overgrown area on the first cheek tooth.

- Ramp: If a horse tends to develop a hook, this usually indicates a type of alignment of the teeth that will result in a ramp in the opposite arcade on that same side. A ramp is an overgrown tooth at the back of the mouth that restricts the horse’s ability to chew side to side, resulting in an abnormal open-mouth chewing motion. Owners will often see their horse drop large amounts of feed when this is the case. A quick look in the horse’s mouth usually does not allow the practitioner to see all the way to the last tooth to identify any ramp overgrowth; a sedated exam with equipment to hold the horse’s mouth open is required to assess the degree of overgrowth.

- Waves and Steps: A wave is described as an overgrown area spanning multiple teeth, opposed by overworn teeth. This usually occurs toward the middle of the row of teeth (arcade). A step is similar to a wave, except the overgrown area is limited to a single tooth. Both of these types of imbalance can also restrict chewing motion and can lead to health issues as described below.

- Incisor Overbite/Underbite in Incisors: Horses also are prone to developing an overbite and, less commonly, an underbite on their incisors, which can sometimes lead to restricted chewing motion.

A horse may also have a restricted chewing motion if there is a painful area within his mouth or head or if there is a congenital defect or neurological issue. In my experience, the most common balance issue that causes restricted chewing is the presence of a ramp at the back of the mouth.

There is clinical evidence that restricted chewing motion or chewing on only one side of the mouth on a consistent basis will result in asymmetric chewing muscles on the outside of the horse’s head as well as a potential for pain around the temporomandibular joint (behind the eye and below the ear, where the lower jaw connects to the skull, see diagram above), although the latter has not been proven scientifically. In my experience, horses with restricted chewing motion usually have a resistance to bending or picking up a specific lead when being ridden. I have found that many of these horses receive regular chiropractic, massage or acupuncture treatments, but few show full benefit from these treatments until their mouths are properly addressed.

When a horse is presented for dental examination, causes of imbalance must be identified and any overgrown teeth should be reduced appropriately, even if he lacks sufficient sharp enamel points to consider him due for floating.

Dangers of Imbalance and Gingivitis

If imbalance advances far enough so that feed gets packed between teeth, then gingivitis, or inflammation of the gums, can set in. Gingivitis usually becomes chronic as the feed material is degraded by bacteria. The gingiva—gum—will lose some of its attachment to the tooth, which usually results in an even deeper space for feed material to become trapped in. Eventually, this can break down the periodontal ligament holding the tooth in place, loosening the tooth. This process is quite painful and can be the reason many horses are head shy or react to oral examination and floating, even with adequate sedation. If specific upper teeth develop infection around the roots, the potential for sinus infection can also exist.

Horses can experience feed-packing with associated gingivitis between the incisors as well. Ramps and hooks can also lead to feed-packing. As the overgrown last lower tooth presses against the last upper tooth, over time the lower tooth will be pushed from the front, so that it rocks backward. This chronic stress can be likened to braces on a person’s teeth. Eventually the lower tooth will shift, opening a gap for feed material to become chronically entrapped in. The same process also can occur when a horse’s hooks are left unaddressed. Once a space forms for feed material to become lodged in, this usually results in a chronic, painful issue for the horse if left untreated.

Usually canine teeth accumulate tartar, which should be cleaned by your veterinary dentist to reduce the possibility of gingivitis developing in that area.

Importance of Routine Care

Since the horse’s teeth are not readily visible, unlike lameness, injury or overgrown hooves, they can be forgotten. Most owners are not aware of the abnormalities present in their horse’s mouth and thus, these issues may not be addressed in a timely fashion. In fact, it seems many calls that I receive are for horses who have not been floated in years and are having difficulty eating, are dropping feed or having problems with the bit when ridden. In most of these cases, the problems are beyond repairing in one session or may even be so severe that fixing these issues is not possible.

An excellent way to give your horse the best opportunity for a comfortable, efficient set of teeth is to have them properly examined at an appropriate interval. My recommendation is as follows:

- Begin floating horses when they are 2 years old with biannual examinations with floating until age 5 (when all adult teeth should be fully in place).

- Horses 5 years old until roughly 7–8 years of age ought to be examined every nine months.

- Horses roughly 8 years old to geriatric age (around 20 years old) are seen once yearly

- Horses of geriatric age are generally seen twice yearly

If horses in any of these age groups are known to have dental abnormalities, they should be seen at least twice yearly to attempt to manage or correct any issues.

Erupting versus Growing

In the world of equine dentistry, the term “erupting” is different than “growing.” By the time a horse is 2–4 years old, his teeth are at the maximum length, but they have a very long root. Throughout the horse’s lifetime, the teeth are constantly being pushed into the horse’s mouth from the root area at the same time they are being worn down. This is why older horses have shorter roots and tend to lose more teeth.

Canine teeth are the single, large teeth that are located between the incisors and cheek teeth. Shortening them is not recommended because of their increased risk of fracture and the likelihood of damaging their internal structures.

Wolf teeth, if present, are located in front of the first cheek tooth. Some horses do not develop wolf teeth, but if they do, they can fall out on their own or are generally removed at a young age, as they can be a cause of discomfort when the horse is bridled. This is usually a result of their sharp tip and their small roots, which allow the tooth to wiggle when pressure is applied. Care should be taken not to fracture the root when this tooth is extracted; specialized tools are available to help your veterinary dentist accomplish this.

Criteria For Choosing An Equine Dentistry Professional

- The person should always perform a thorough head and oral examination under sedation using an oral speculum to keep the mouth open.

- He or she should prepare a detailed medical record describing any dental abnormalities.

- Any abnormal teeth or areas of teeth should be addressed (which may require X-rays or extraction of teeth).

- The mouth should be well balanced (without overaggressive reduction) and sharp enamel points should be rounded off.

- Incisor teeth require attention as well.

- Packed feed and tartar should be removed.