By nature, equestrians ride on the basis of human assumptions, imagining—if we ponder it at all—that the horse visualizes depth and color the same way we do. We also assume that other equine senses are subordinate to vision, as ours are. Because of misinformation concerning night vision and our own inexperience with it, we presume that horses see details in the dark with superhero sensitivity. The reality is quite different. Doubling down on these discrepancies between human and equine sight explains many common problems within the horse-and-human team. Here we take a look at the horse’s depth perception.

This article was adapted from “Horse Brain, Human Brain” by Janet L. Jones, PhD and is available at HorseandRiderBooks.com.

Eyes admit physical views, but it takes a brain to compute visual distance. When staring straight ahead, humans take in two views of a given sight—one from each eye. To see this for yourself, hold your finger in front of your nose at arm’s length. Close one eye and line your finger up with something vertical in the distance—a door frame or a fence post, whatever. Now open that eye and close the other. Your finger will appear to jump back and forth as you alternate eyes. Those are the two views that your right and left eyes send to your brain. The brain calculates the difference between them, and as if by magic, you become aware of depth. Using this automatic computation, you can look at a field of horses and note that the cute roan is farther from you than the pretty paint.

Human depth perception is extremely precise because our eyes are so close together. They are also yoked, moving in concert with each other for precise tracking. With this design, the average person can distinguish ¹⁄8 of an inch in depth from a distance of 16½ feet. In other words, if you were standing one long stride away from the takeoff to a double-rail vertical, your brain could tell you whether one of the rails was set ¹⁄8-inch behind the other one. That’s depth perception on steroids!

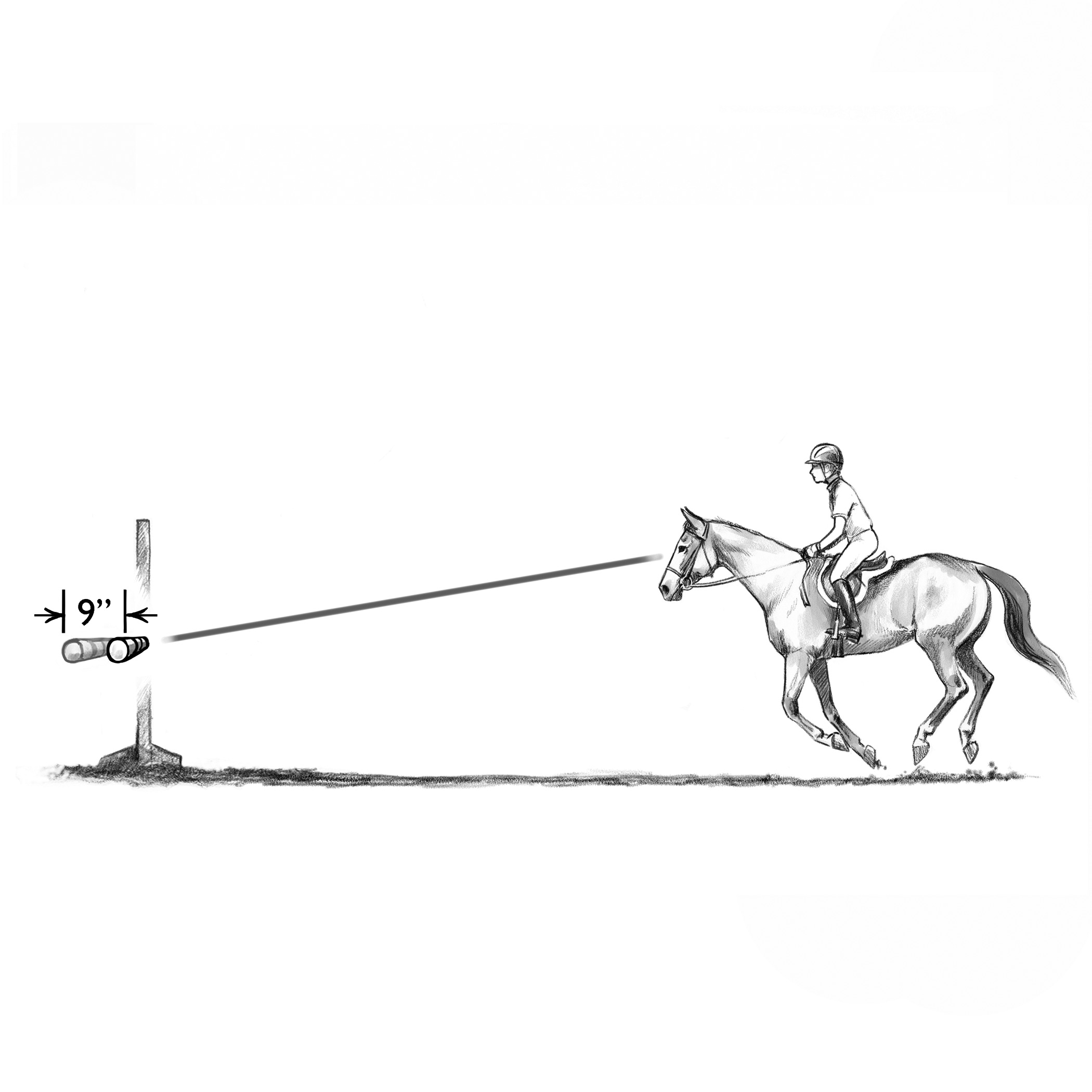

By contrast, the smallest amount of depth a horse can detect when standing the same distance away from something is 9 inches. Human stereoacuity is 72 times sharper than that.

Horses’ ability to see depth is limited because their eyes are set so far apart. From most angles, horses cannot get a left-eye and right-eye view of the same object in one glance. We hominids can see an outstretched finger with both eyes simultaneously. But even in a rearing position, Twinkletoes would have to be a contortionist to get his hoof in front of both eyes at the same time. As prey animals, horses are built for peripheral motion detection at the expense of depth perception. As predators, we’re built in reverse.

For horses in disciplines like dressage, reining or pleasure, depth perception is not so critical. But consider cutting, barrel racing or jumping. A horse needs to know how far away relevant objects are and how fast those distances are changing as he moves. A horse can improve depth perception by raising his head, dropping his withers, or lifting his nose, but this often complicates his task. In cutting, for instance, horses need to keep their eyes down on the cow and their heads low to make quick turns. In jumping, they need impulsion from their hindquarters to power off the ground and abdominal tuck to lift their legs. The physics of such movements require horses to maintain a round back for core strength, which often precludes the position of a high head.

The distinction between hunters and jumpers is also important here. Top jumpers are judged by the clearance and speed of their rounds over high, wide fences—fences that are often approached off sharp turns from short distances. Such horses are often selected as jumpers because their necks are set high on the withers, with head position proportionately higher. Those without that conformation are encouraged to approach jumps with their heads raised. If you watch a jumper approaching a fence, you’ll see his head lift in the last stride or two. This natural form provides both eyes with a brief view of the jump, so that the equine brain can determine its height and width. But the view is indeed brief—fractions of a second—and it’s late.

Occasionally, we hear that jumpers are aided in depth perception by wagging their heads back and forth on approach, to allow each eye a view of the jump. This suggestion does not hold up in terms of brain science. To compute distance, the brain requires a simultaneous view of the object with both eyes. Wiggling the head back and forth only interferes with centering the horse. It probably also prevents him from concentrating on other cues from the rider that are much more important.

Depth perception is easier for hunters. These horses are judged on the quiet beauty of their jumping form and are taught to maintain a long frame with hindquarters engaged, necks arched long, heads low and faces nearer the vertical to form a strong topline. This position can be preserved over fences because hunters are given a long approach with which to see relatively low jumps without raising their heads. Good hunter riders encourage horses to look at a fence while rounding a distant corner. This supplies the horse with a better side view, a longer front view, and more time for the two eyes to send images of the jump to the brain. It’s still a good idea, of course, to allow any jumping horse some freedom in moving his head to improve his view.

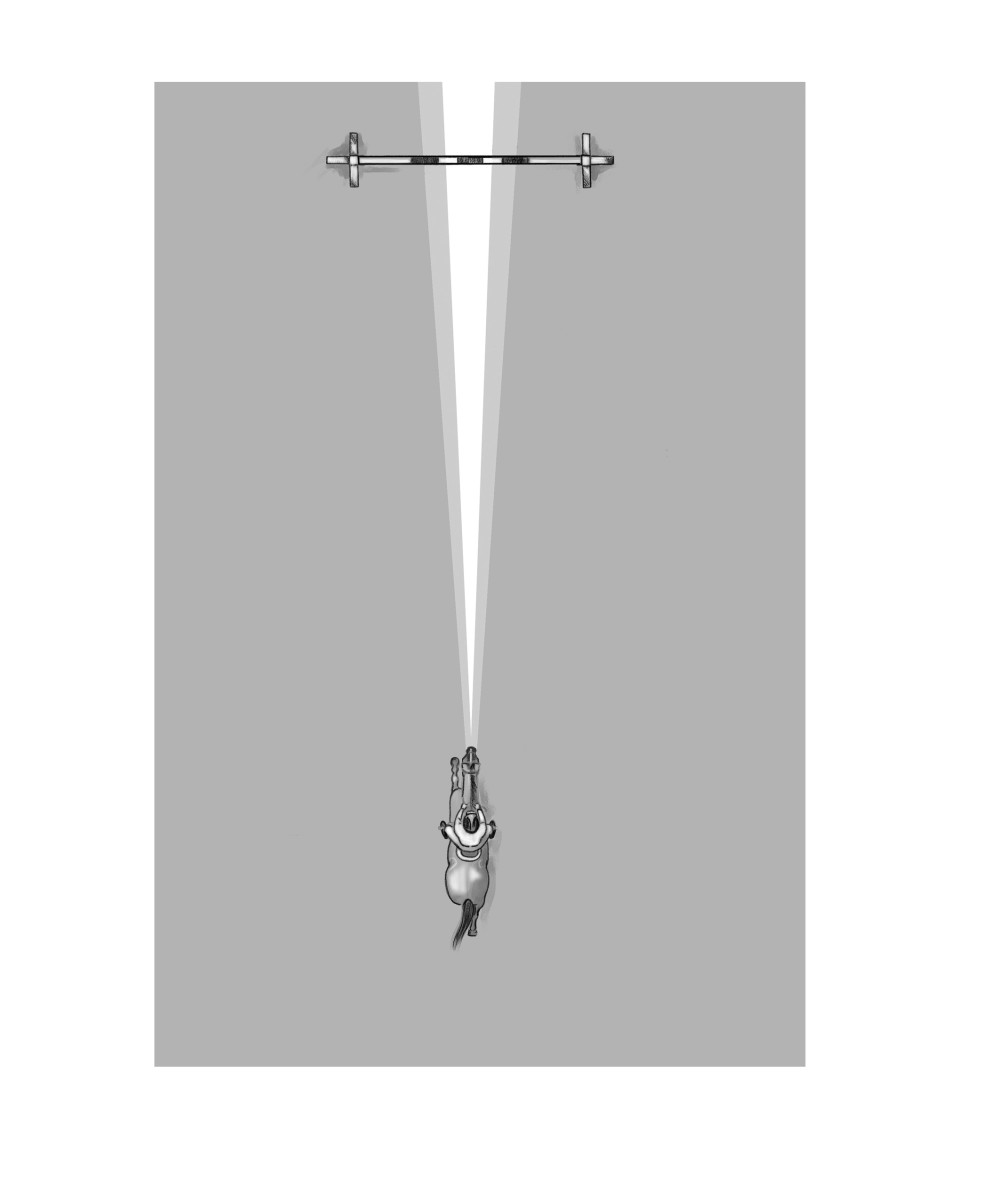

In terms of width, only about half the area visible to two human eyes at the same time is visible to a horse’s two eyes at the same time (see image above). Stand about 30 feet back from an arena fence. Roughly 5 feet of that fence is clear and sharp to both of your eyes as you hold them still. From the same position, only half of that—about 2½ feet—is clear to both the horse’s eyes. And it is only that small portion visible to both eyes for which a brain can calculate depth by stereoacuity.

When you’re aiming a horse toward a fence, center him on the narrow middle portion that he can see with both eyes. Many early jumping errors occur when a rider does not steer the horse to the center of a jump. These problems are frequently blamed on the horse—he ran out, he refused, he chipped, he jumped in bad form. Well, that’s not because he’s a bad horse; it’s because the rider didn’t let him see the fence!

This article was adapted from “Horse Brain, Human Brain” by Janet L. Jones, PhD and is available at HorseandRiderBooks.com.