Viscous, straw-colored mucus lingered on my vibrant 5-year-old Thoroughbred’s right nostril, punctuated by a dark trickle of blood that returned minutes after I wiped it away. A few days later, the volume of discharge increased, but my horse seemed otherwise healthy. He had no fever, a good appetite and was enthusiastically learning to jump under saddle.

Unseen past the dark recesses of his nasal passages was a mass growing in his sinus. A veterinarian soon identified the growth as a progressive ethmoid hematoma, a benign tumor at the back of the nasal passages, that required surgical removal.

This is just one of several types of sinus disease that occurs in horses and will be described in this article. But first a basic understanding of the equine sinuses will help.

Equine Sinuses Defined

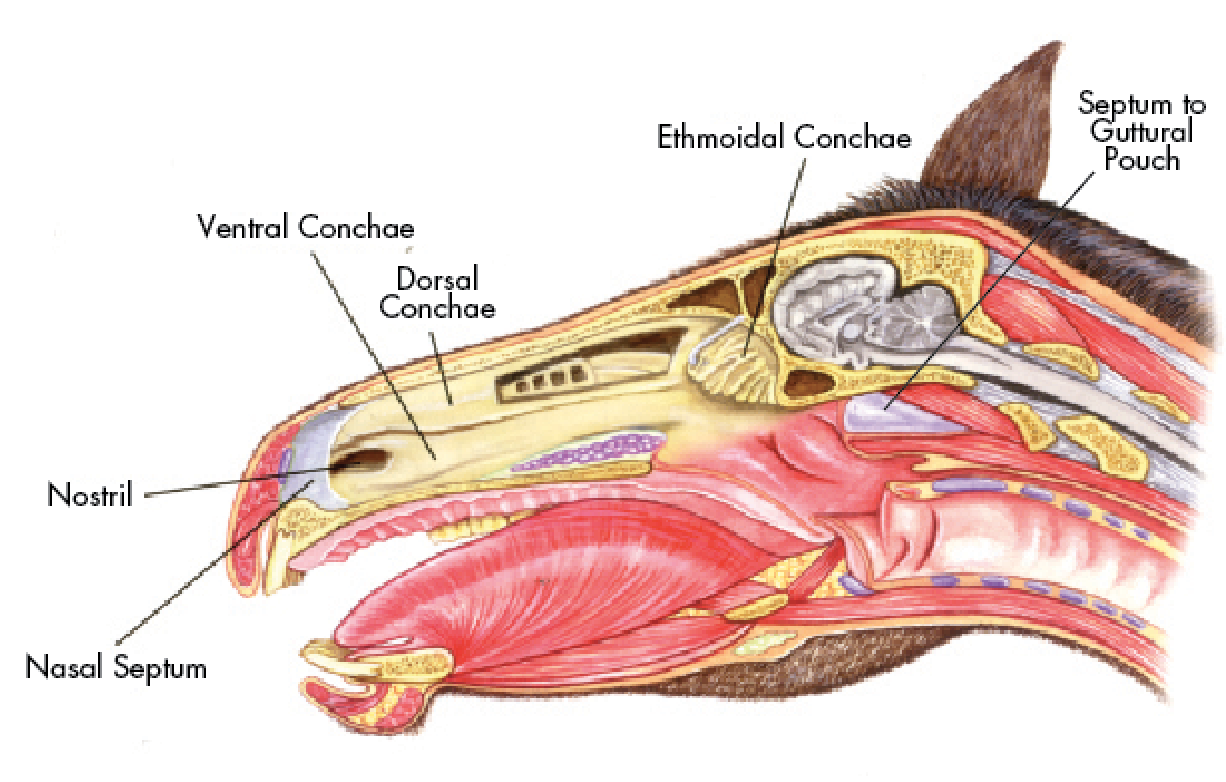

Sinuses are air-filled cavities located on either side of the horse’s head, above, below and between the eyes. They extend down the face to the lower end of the cheekbones. Often referred to as paranasal sinuses because they are near the nose, sinuses have a smooth interior lining and are covered by a thin layer of bone.

There are six pairs of paranasal sinuses on each side of the horse’s head.

- The two frontal sinuses are closest to the surface of the forehead.

- The two maxillary sinuses are the largest sinuses and divided by a thin wall (septum) into two parts called rostral and caudal. The maxillary sinuses house the roots of the molars.

- The remaining pairs of sinuses are called dorsal conchae, middle (ethmoidal) conchae, ventral conchae and sphenopalatine sinuses.

These sinuses communicate with each other via a complex network of passages. Each side of the sinuses is separated by the nasal cavity and the long nasal septum, except toward the back (dorsally) of the skull, where the frontal sinuses have their own septum. The frontal sinuses communicate with the maxillary sinuses through a silver-dollar-sized opening.

The exact function of the sinuses is unclear. They may have evolved to allow the horse to have a large enough head to fit his many teeth but not add the weight of solid bone. Membranes in the sinuses also are thought to produce some mucus to help moisturize the nasal passages, which extend from the nostrils to the windpipe, and to protect the respiratory system from dust, dirt and microorganisms. They also may be holding chambers for mucus produced elsewhere in the respiratory system.

In a healthy horse, mucus flows through the sinuses, ending with the maxillary sinuses, where it then drains into the nasal passages through a narrow opening and out through the nostrils.

“Normal mucus should appear after exercise or after the horse has had its head down for a prolonged period of time,” says Elizabeth J. Barrett, DVM, MS, DACVS-LA, a veterinarian at the Hagyard Equine Medical Institute. “It should not be persistent and of a large volume. It should typically be clear in color and not malodorous.”

Mucus containing pus or blood that may be accompanied by a foul odor is frequently the first sign of a problem in the sinuses. “Nasal discharge that needs to be investigated further persists for longer than a day or two, is purulent [contains pus] or bloody or smells bad,” Dr. Barrett says.

Diagnostic Tools: Finding the Source

If your horse has bloody or purulent mucus coming from his nose, a veterinarian first will try to find its source to determine why it’s happening. She’ll pass an endoscope, an optical instrument that allows a vet to see inside the body, through the nasal passages. From there, she may be able to see discharge in the general area of the sinuses. “That is the hint that drainage is coming from the sinus,” Dr. Barrett says.

A veterinarian then may move on to other diagnostics because the sinuses cannot be accessed with a scope. At this point, she may take radiographs or refer your horse to a clinic or equine hospital to have radiographs taken to check for a fracture or growth. However, if an infection has produced dense fluid, a veterinarian may have difficulty interpreting the X-rays. If she can’t make a definitive diagnosis, she may opt for alternative diagnostics, such as computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or a sinoscopy.

A veterinarian can use a CT and an MRI to better view and evaluate soft tissues and tumors because they provide more detailed imaging than X-rays. A CT is a combination of several X-rays that create a cross-sectional view of the inside of the body. An MRI also provides a cross-sectional image of the body, but it uses a magnetic field and radio waves. Some equine hospitals can perform a CT while the horse is standing, while others require a vet to give your horse general anesthesia and lay him down, also the procedure for an MRI.

If the veterinarian does not think a CT or an MRI provides enough information for a diagnosis, she may recommend a sinoscopy. During this procedure, she will make a small incision in your horse’s skull and pass an endoscope directly into the sinuses to evaluate the color, size, shape and location of an infection (sinusitis) or growth.

These diagnostic tools will help your veterinarian pinpoint the cause of the abnormal discharge. Such discharge may be caused by sinusitis or a more serious sinus disease, such as a growth in the sinuses.

Sinus Infection

Common in horses, sinusitis falls into two categories: primary and secondary.

Primary sinusitis is caused by bacterial infection, most commonly a Streptococcus, possibly from an upper-respiratory infection. The result is pus buildup and inflammation of the lining of the sinus, leading to bloody or pus-like discharge from the nostril that is on the same side as the affected sinus (unilateral). The discharge may have a malodorous smell as well.

After a physical examination of your horse, a veterinarian will pass an endoscope through his nose and may move on to radiographs or a CT. Once an infection is determined, it can be treated with antibiotics or, in more severe cases, a lavage (flushing) of the sinuses. After your horse is sedated, a small hole is made in the facial bones to access the sinuses for irrigation.

Secondary sinusitis is an infection caused by another source, such as a diseased or broken tooth or tooth root. Molar roots of the upper jaw are within the maxillary sinuses, says Kenneth E. Sullins, DVM, MS, DACVS, a professor of surgery at Midwestern University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. If they become infected and erupt into the sinuses, secondary sinusitis will occur. The signs are the same as for primary sinusitis, but the associated smell is more likely to be worse.

“Sometimes it’s just bad luck if they get a tooth infection, but it can also be caused by a fractured tooth or diastema [packed food] between teeth,” adds Dr. Barrett.

An oral examination, endoscopy and radiographs will help to confirm secondary sinusitis. To treat it, a veterinarian will extract the bad tooth or push it out through the sinus. This type of sinusitis is fairly common but may be prevented with regular dental care and maintenance.

Ethmoid Hematoma

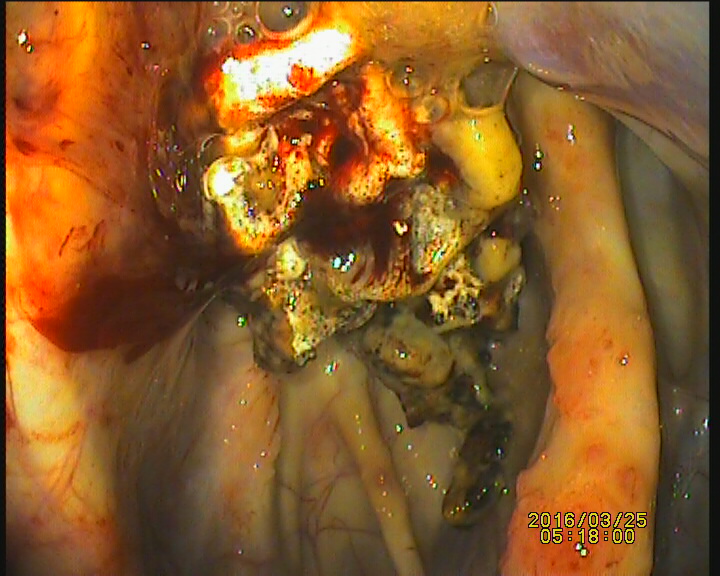

Another reason for abnormal nasal discharge is an ethmoid hematoma, a benign tumor with a smooth exterior that is often mottled red, yellow or purple. It typically originates in the scroll-shaped bones at the back of the nasal passages called ethmoid turbinates. It also sometimes occurs in the maxillary sinuses. The cause is unknown.

If the soft, fragile, blood-filled ethmoid hematoma is in the ethmoid turbinates, a veterinarian can identify it with an endoscope. If it’s in another part of the sinus, she will have to X-ray to see it and possibly move to a CT or an MRI.

Once confirmed, an ethmoid hematoma must be removed. If left untreated, it may continue to grow until it blocks the horse’s nasal passages and interferes with his breathing. There are multiple treatment options, depending upon the size and exact location of the mass.

To treat a very small ethmoid hematoma—under the size of a small grape—a veterinarian may perform endoscopy of the nasal passage and use an endoscopic needle to inject the mass with a solution of formaldehyde called formalin. This is an inexpensive, minimally invasive procedure performed under standing sedation at a clinic. However multiple treatments are usually required.

There is a small risk of a negative, allergic-type response to formalin, where a sudden and severe inflammation occurs in the sinuses. For example, after an injection to treat my young horse’s ethmoid hematoma, his breathing became labored, requiring a midnight emergency trip to the hospital. It also is possible that the mass will not respond adequately to this treatment.

An alternative to formalin injections for a mass no larger than the size of a grape is to vaporize it using a scope-guided laser through a sinoscopy incision. A veterinarian can perform this procedure while the horse is under standing sedation. Depending on the size of the mass, multiple treatments may be needed to completely obliterate it. However, the horse usually experiences very little discomfort and recovers quickly.

For medium to large masses, the best way to access the sinuses and ensure that all abnormal tissue has been removed is to perform a frontonasal bone flap. In this invasive surgery, a horse is sedated and standing or under general anesthesia. A veterinarian will inject a local anesthetic under the skin where he will perform the bone flap surgery Using a bone saw or an instrument similar to a chisel (an osteotome), the veterinarian will make a reverse D-shaped incision in the bone and then pry up and secure open a flap of bone. The surgical team will remove the mass through the opening and then push the flap back down and secure the skin with staples and cover it with a pressure bandage. (See the sidebar, “Bone-Flap Surgery,” p. 35, for more information.)

Ethmoid hematomas have a tendency to recur if not completely removed, although the reason is not known. Follow-up endoscopies are recommended to check for recurrence and the horse’s owner should carefully observe nasal discharge for signs of blood.

Cysts

A cyst is a mass in the sinus that Dr. Sullins describes as a “thin, mucosa-lined, bony ‘balloon.’” Pink mucosa also covers the balloon, which contains yellow mucus. Like an ethmoid hematoma, a cyst’s cause is unknown, however developmental problems have been suggested. A cyst is most likely to be found in the ventral conchae, frontal or maxillary sinuses.

If a cyst obstructs normal sinus drainage, pus will drain out of the nostril on the affected side. The discharge varies in terms of the presence of blood or odor. Cysts can exert a lot of pressure in the small spaces of a sinus and can cause painful facial swelling. If ignored, this may cause decreased blood flow to the facial bones, leading to necrosis (death of tissue cells) and recurrent infection. Cysts also can cause airway obstruction.

During an endoscopy, if a cyst is in the sinuses, it may be visible in the nasal passages, the nasal passages may appear narrow or they may be obstructed. Radiographs will reveal distortions of the sinuses or septum caused by the pressure of the cyst that may need to be repaired during surgery. As with an ethmoid hematoma, a veterinarian may choose to use a CT or an MRI or perform a sinoscopy during diagnostics.

A cyst must be surgically removed, but unlike an ethmoid hematoma, it is not likely to recur. A possible side effect is more frequent, though non-life-threatening, mucous discharge into the nasal passages because of the removal of the associated sinus lining during surgery.

Neoplasia

In rare cases, a mass in the sinuses will be cancerous, called sinus neoplasia. The most common types of malignant tumors are squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and adenocarcinoma.

The signs of sinus neoplasia are unilateral discharge containing mucus and pus, facial swelling and reduced airflow. It is possible that the discharge contains blood and is bilateral—coming out of both nostrils. In advanced cases, the horse may show neurological deficiencies.

A veterinarian will take a sample of the mass and perform a biopsy to confirm sinus neoplasia. While the mass can be surgically removed, the results are usually unrewarding and there are few alternative treatment options. Dr. Sullins explains that systemic chemotherapy is extremely expensive with a dire prognosis. Local chemotherapy, where the mass itself is treated, is possible but not usually a long-term solution in

the sinuses.

“The problem with a malignant tumor in the sinus is it is, by definition, invasive,” Dr. Sullins says. “An ethmoid hematoma is not; it’s just sitting on the surface. If a squamous cell or adenocarcinoma has gotten into the bone and lymph nodes, treating the site is not going to work.”

On a personal note, my horse underwent a successful bone-flap surgery at age 5 to remove his first ethmoid hematoma. It had been lying on a flat surface of bone, so the entire mass was easily cleaned out. He recovered and competed in eventing for many years, eventually progressing to the Preliminary level.

When he was 14, the telltale trickle of blood returned. Considering his history, a veterinarian immediately scoped him and found another ethmoid hematoma. It was located in a difficult area, high in the ethmoid turbinates. The mass was removed using a scope-guided laser and cleaned during a standing surgical procedure.

In a worst-case scenario, six months later my horse developed a separate adenocarcinoma that began to invade his brain. His health rapidly deteriorated and just as a biopsy confirmed the cancer, he started to display severe neurologic symptoms. Euthanasia was the only option.

Because of the complexity of the equine sinuses, Dr. Barrett encourages owners to “seek a veterinarian with experience in this area. There are people out there that love dealing with sinuses. If there is an option to refer or travel, it is important to be willing to do that.”

When it comes to sinus disease, awareness and efficiency may make all the difference. Do not ignore a bloody nose or nasal discharge containing pus or a foul smell.

Emergency: Guttural Pouch Mycosis

While sinus disease is not usually considered an emergency, a nose bleed should never be underestimated. It could be the sign of a rare, life-threatening fungal infection called guttural pouch mycosis.

A horse has two large guttural pouches, one on each side of the head, located high in the skull beneath the ear. They cool blood during exercise, particularly regulating the temperature of blood flow to the brain. The pouches are covered by a thin membrane, beneath which are important arterial veins and cranial nerves.

If a fungus has grown on an artery in a guttural pouch, it can cause fatal hemorrhaging due to arterial damage. If a horse has a nose bleed, a veterinarian usually first will check for a guttural pouch mycosis with an endoscope.

“It’s important to differentiate,” says Kenneth E. Sullins, DVM, MS, DACVS, a professor of surgery at Midwestern University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “With guttural pouch mycosis, the bleeding will be bright red and profuse. It’s not something you’ll mix up with an ethmoid hematoma. Mycosis is an emergency.”

Blunt-Force Trauma

Abnormal nasal discharge and facial deformities do not always point to a sinus disease. A horse may suffer a fracture due to blunt-force trauma from swinging his head recklessly or getting kicked by another horse. Because the blood supply in the head is so good, a small fracture will usually heal very well on its own.

A veterinarian may do reconstruction if there is a depression or fragments of bone seen on an X-ray. The prognosis is usually promising. Kenneth E Sullins, DVM, MS, DACVS, a professor of surgery at Midwestern University’s College of Veterinarian Medicine, describes a case where a foal had been kicked and his face caved in. During surgery, Dr. Sullins elevated the bones and re-inflated the sinuses. The foal healed extremely well and went on to become a halter horse.

Bone-Flap Surgery

Bone-flap procedures sound gruesome, and while they are messy, horses tolerate it well, says Kenneth E. Sullins, DVM, MS, DACVS, a professor of surgery at Midwestern University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. The wound also heals nicely because of good blood supply in the head. “Horses are pretty tough. Give them some phenylbutazone and that same evening they’ll have their head stuck in a hay bag.”

However, sinus surgery can be risky and time is of the essence because the good blood supply that promotes healing can hinder surgery. During a standing procedure, the horse must remain quiet so the veterinarian can work quickly and accurately. If the horse repeatedly shakes or jerks his head, surgery with the horse lying down under general anesthesia may be necessary.

With standing sinus surgery, there is less blood loss because the horse’s head is above his heart. When he is lying down under general anesthesia, there may be increased blood loss because the horse’s head is lower. Some horses also panic and thrash when coming out of sedation, risking injury.

If bleeding becomes profuse or blocks visibility during surgery, the sinus can be packed with gauze to stop the bleeding. The flap may then be closed and another standing surgery performed a few days later to remove any remaining pieces.

“It’s not usually the lesion itself that bleeds. What bleeds is normal mucosa and vessels when you rip them. You have to get out as quickly as you can without causing hemorrhage,” Dr. Sullins says.

Even if there is no profuse bleeding and Dr. Sullins is able to complete a surgery, he usually will re-open a flap and re-evaluate in two or three days. “A huge component of sinus disease does not go away on the first surgery and the reason is you can’t see with the bleeding. So unpack it, flush it out, put a scope in there and look at all the corners. My opinion is that’s what makes [the treatment] work.”

Dr. Sullins studied 91 cases of horses who underwent standing sinus flaps using this post-operative treatment protocol and published his findings with co-author Samantha K. Hart in the Equine Veterinarian Journal in 2011. In a paper titled “Evaluation of a novel post-operative treatment for sinonasal disease in the horse,” they concluded this to be a “safe and effective means to thoroughly assess and treat sinonasal disease” that may help “reduce long-term complications and recurrence rates.”

This article was originally published in the January 2018 issue of Practical Horseman.