Your horse trots up to meet you at the pasture gate, and you can see right away that he’s off. You don’t see any sign of injury. “Maybe he stepped on a rock,” you think. You give him the day off, but the next day he’s still sore. You call your veterinarian.

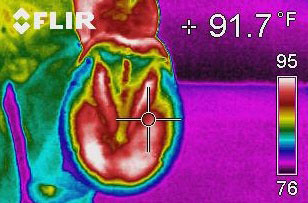

Thermography, which produces images of heat patterns on the horse’s body surface, is one of several high-tech imaging techniques now available to veterinarians as tools for the diagnosis of lameness problems. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine Imaging

Thermography, which produces images of heat patterns on the horse’s body surface, is one of several high-tech imaging techniques now available to veterinarians as tools for the diagnosis of lameness problems. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine ImagingWhat can you expect when the vet arrives? Finding the cause of lameness is like solving a challenging puzzle. It takes knowledge, experience and often time, says Kent Allen, DVM, a specialist in equine sports medicine, lameness and diagnostic imaging in Middleburg, Virginia. In this article Dr. Allen describes the process and explains how and when some high-tech imaging techniques can help.

These techniques are giving veterinarians new insights into many lameness problems. But, Dr. Allen says, “The most useful tool in the box is still the veterinarian’s expertise. Everything else can be confused.”

First Step: Hands On

The process starts with a lameness exam—a detailed physical exam that looks for abnormalities in gait and signs of injury or inflammation in joints, tendons and other tissues. As part of the exam, your veterinarian will:

• Watch your horse move. The trot is the most telling gait—lameness shows up as asymmetry there, and the pattern usually suggests which limb is involved. The vet will watch the trot on the straightaway and in circles in both directions and, perhaps, on hard and soft ground, on a slope or with and without a rider.

• Check and palpate the limbs carefully for heat, swelling and soreness, comparing opposing limbs to detect abnormalities.

• Apply pressure with hoof testers to locate abnormally sensitive areas in the foot.

• Move the joints through their normal range of motion to check for stiffness and soreness, again comparing opposing limbs.

• Perform flexion tests, in which a joint is held flexed for 45 seconds or a minute before the horse is trotted off. These tests often make subtle lameness more apparent.

Depending on what the exam shows, the veterinarian may confirm the location with one or more nerve blocks—injections of local anesthetic to temporarily deaden nerves that serve specific regions of the foot or lower limb. This is done systematically, one region at a time, until the lameness disappears.

While the basics of the exam haven’t changed, new technology is helping the process. “We have digital gait-analysis systems that can be used in the field or clinic, not just at university research centers,” Dr. Allen says. His practice uses Lameness Locator, a system of inertial sensors and gyroscopes that detects asymmetry in gaits. The system gives an objective assessment of whether a horse is lame, how severe the lameness is, which limb or limbs are involved and where in the stride peak pain occurs (impact, mid-stance or push off). But it’s not enough on its own.

“It’s a tool and it needs an experienced clinician to interpret the results. That’s true of all the tools we use,” Dr. Allen says. “Suppose hoof testers show the horse is sore in the heel, but when you block the heel he doesn’t trot sound. That doesn’t mean either test was wrong; it means the results need to be interpreted as part of a broader picture. That’s the clinician’s job.”

Once you have an idea of where the horse is sore, the next step is figuring out why. That’s where diagnostic imaging usually comes in. The results of the lameness exam tell the veterinarian which of the different imaging methods used today is most likely to produce an answer. Here’s what you can expect with each.

Digital Radiology

Direct digital radiography allows X-rays to be reviewed on a high-resolution screen within seconds. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine Imaging

Direct digital radiography allows X-rays to be reviewed on a high-resolution screen within seconds. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine ImagingDirect digital radiography (DDR) provides the veterinarian with an X-ray image that can be viewed on a high-resolution screen within seconds, without the need for film developing.

When it’s useful: DDR can detect or rule out fractures and identify damage or defects in bony tissue.

How it works: The system uses a conventional X-ray camera to expose a digital cassette or detector, which captures the image and sends it to the screen. The image can be adjusted or enhanced on screen.

Where it’s done: There are portable systems for use in the field and more powerful systems for use in clinics. Since its introduction in 2002, DDR has become widespread. It’s the standard for veterinary radiology now, Dr. Allen says: “There are not many circumstances where you’d use film.”

Advantages:

• You get instant results. Fractures and catastrophic bone injuries can be ruled out within seconds.

• Image quality is more consistent with better detail than film.

• Brightness, contrast, magnification and edge enhancement are easily adjusted, so there are fewer repeat exposures and less sedation for the horse.

• Images can be emailed immediately to referring veterinarians or for second opinions and stored electronically so owners and trainers can keep them.

Limitations: “Not all digital machines are equal, so sometimes we still see poor quality images,” says Dr. Allen. “You should ask for a copy (copying costs are minimal) and how long the vet will store them. Some clinics have very sophisticated storage systems while some new vets starting up may have none,” he adds.

Cost: Routine shots range from $30 to $45 each, depending on where you live and the quality of the system.

Diagnostic Ultrsound

Detailed images produced by diagnostic ultrasound can help evaluate injuries and inflammation in tendons, ligaments and other soft tissues. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine Imaging

Detailed images produced by diagnostic ultrasound can help evaluate injuries and inflammation in tendons, ligaments and other soft tissues. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine ImagingDiagnostic ultrasound, which creates images with sound waves, has also gone digital.

When it’s useful: Ultrasounds help evaluate injuries and inflammation in tendons, ligaments and other soft tissues, including tissues around joints. The scans reveal tears in the fibers of tendons and ligaments and accumulations of fluid that indicate inflammation in any soft-tissue structure. They can show bone surfaces in joints, too, but not the inner structure of bone. Ultrasound imaging is also used to guide injections into joints and other structures.

How it works: A handheld probe emits high-frequency sound waves that travel into the horse’s body. Ligaments, tendons, bone and other tissues reflect the sound waves in different degrees, based on their density. The probe captures the echoes and sends the information to a processor that creates an image. Fluid, which is the least reflective, shows up black. Bone, the most reflective, appears white. Other tissues are various shades of gray.

Where it’s done: In the field, with portable equipment, and at clinics. Larger clinics are more likely to have high-resolution ultrasound and special probes for specific areas, such as the bottom of the foot or the pelvis, as well as expertise in guided injection techniques.

Advantages: The scan is non-invasive and produces detailed images that can be stored electronically, emailed or printed.

Limitations: “Ultrasound is operator dependent. A clinician can have the best equipment available and still get poor images if he or she doesn’t have expertise,” Dr. Allen says. “And expertise is site-specific—knowing how to get good images of a tendon won’t help you get good images of the fetlock. That means clinicians need to have training.”

Cost: Typically around $200 to $300, depending on where you live.

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy can identify areas of bone inflammation caused by injury or disease. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine Imaging

Nuclear scintigraphy can identify areas of bone inflammation caused by injury or disease. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine ImagingNuclear scintigraphy—a bone scan—highlights bone metabolism. It identifies areas where bone is undergoing remodeling as a result of injury or disease.

When it’s useful: A bone scan is most helpful when other techniques fail to locate the source of a lameness problem. Your veterinarian may suggest a scan if:

• Your horse is lame but doesn’t block sound or shows no abnormalities in X-rays or ultrasound.

• He’s lame in multiple limbs.

• The vet suspects a hard-to-locate upper-body problem.

• Your horse not performing up to his usual level, and other diagnostic work doesn’t pinpoint the cause.

The scan can turn up a range of conditions that involve bone inflammation. For example, the horse might have a fracture or a stress fracture, an avulsion (in which a ligament tears away from bone, taking a bit of bone with it), sclerosis (degeneration) of the bone beneath cartilage in one or more joints or a bone infection. If the scan shows nothing, the problem more likely involves soft tissues.

How it works: The horse gets an intravenous injection containing a short-acting radioisotope linked to bone tracer agent. He’s stabled in a secure stall while the radioisotope circulates throughout his body, and then he’s tranquilized and imaged with a gamma camera. The scan can cover the whole body, just the front end or just the hind end. Areas where bone is undergoing remodeling absorb high amounts of the radioisotope, and these areas show up as “hot spots” on the computerized image that the camera produces. The image shows whether the activity is focused or diffuse, and mild, moderate or intense.

Where it’s done: A bone scan requires a trip to a clinic that offers this test; most university and some private equine clinics do. Expect the horse to be there at least two days—the prep, the scan and the follow-up are all time consuming.

“We ask that horses come in the night before to keep limbs warm so there’s good circulation when the scan is done,” Dr. Allen says. “After the horse gets the radioisotope injection the next day, there’s a time window—two to six hours—when images can be captured.” The images often aren’t reviewed until late in the day, and the findings often lead to further investigation (nerve blocks, for example) or treatments such as joint injections.

Advantages: Scintigraphy is the only imaging method that allows veterinarians to evaluate the horse’s entire skeleton, so it’s a great tool for uncovering hidden problems. It’s also far more sensitive than radiographs in detecting bone inflammation. That means it can detect bone disease in early stages, when treatment is most likely to succeed.

Limitations: The scan highlights areas of bone inflammation, but it doesn’t show what’s causing the inflammation or provide a detailed image of the problem. Once the location is known, though, other imaging techniques are often able to do that.

Cost: Bone scans range from about $1,200 to $2,000, not including additional diagnostic work or treatment that results from the findings.

MRI

Standing MRI systems allow the horse to stand under mild sedation during the scan instead of undergoing general anesthesia. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine Imaging

Standing MRI systems allow the horse to stand under mild sedation during the scan instead of undergoing general anesthesia. | Courtesy, Virginia Equine ImagingMagnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic fields to create detailed cross-sectional images. It’s quickly becoming one of the most important diagnostic tools in equine lameness.

When it’s useful: “MRI is the opposite of a bone scan—it’s localized. We use it to answer a specific question, not to go fishing,” Dr. Allen says. Your veterinarian may recommend MRI if:

• The site of your horse’s pain has been identified, but X-rays and ultrasound haven’t revealed a cause.

• Your vet needs more information to confirm a tentative diagnosis and determine the best treatment and the horse’s outlook for recovery.

• Detailed images of both soft tissue and bone are needed to sort out a complex problem.

MRI is especially helpful for problems inside the hoof capsule, where ultrasound can be difficult. If your horse has heel pain, MRI can show exactly which structures in the heel are the cause—the navicular bone, the ligaments that support it, the lower part of the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) or the navicular bursa, a fluid-filled sac that cushions the bone. For example, it can show erosions on the surface of the navicular bone and adhesions on the surface of the DDFT adjacent to the bone.

How it works: Two types of MRI units are used for horses:

• High-field MRI units have the most powerful magnets and produce the most detailed images. The powerful field is generated within a cylinder, and the horse is anesthetized so his lower legs can be placed into the machine.

• Standing (or open) MRI systems allow the horse to stand under mild sedation during the scan. A C-shaped magnetic coil fits around the area to be imaged, and the scan is done while the limb is bearing weight.

The magnets in standing systems are less powerful and produce less detailed images than high-yield units do, but avoiding general anesthesia (which always carries risks) is a big plus. “Standing is the most common system worldwide,” says Dr. Allen, who uses a standing system located at the Marion duPont Scott Equine Medical Center in Leesburg, Virginia. ”We get good quality images, particularly in the foot, the most common area imaged.”

Where it’s done: Despite the buzz MRI has generated, equine units are not common and are very expensive. University clinics and major private clinics are most likely to have these systems.

Advantages:

• MRI produces images of all tissue types with sharper contrast and more detail and definition than other imaging methods.

• Because it can identify problems so precisely, it allows early treatment and a better outlook for recovery.

• It’s the only technology that can positively diagnose a few conditions, such as swelling in the navicular bone.

Limitations: Current MRI systems can accommodate only the horse’s lower legs. (High field systems can also fit the head and upper neck.) And some leg regions are difficult to image standing.

“Standing MRI works well for areas that are steady, like the foot and the proximal [high] suspensory ligament in the hind limb. It’s not so good on the fetlock and the knee,” Dr. Allen says. The fetlock joint, for example, moves slightly every time the horse shifts his weight; each movement means that the scan has to be stopped and started over again. “It may make sense to start with the bigger magnet and general anesthesia in the fetlock and other upper body parts. The tradeoff is higher cost and risk, so clinician and the owner have to determine if it’s worth it.”

Cost: A standing MRI scan costs about $2,000 to $2,200, Dr. Allen says; a high-field scan, $2,500 or more including anesthesia. The cost can be as low as $1,500 for some university-subsidized units, though.

Thermography

Thermography produces images of heat patterns on the horse’s body surface. Warmer temperatures suggest increased blood flow, which can be sign of inflammation. Cooler temperatures suggest decreased flow, which can be a sign of restricted circulation.

When it’s useful: Thermography is probably most useful as a complement to a lameness exam and to other imaging methods, rather than a primary diagnostic tool, Dr. Allen says. It can help:

• Highlight areas of inflammation in the foot, joints, bones, ligaments, tendons and muscles.

• Monitor healing by detecting lingering inflammation in injured tendons and other structures.

• Find injuries and areas of inflammation in the horse’s back.

• Deter injuries by spotting areas with increased blood flow in horses in training. Changes in heat patterns in tendons can appear up to two weeks before signs of injury, giving trainers a chance to change the horse’s program and perhaps prevent the injury.

• Identify areas with decreased circulation due to swelling or nerve damage.

• Assess saddle fit by showing circulation changes in areas subjected to increased pressure.

How it works: The temperature pattern is recorded with a camera that registers infrared (heat) radiation, and the camera’s electronic processor turns the temperature data into a thermal image that’s displayed on a screen. Different colors represent different temperatures. The veterinarian looks for symmetry, comparing one hind foot to the other or the back of one foreleg to the back of the other. They should look about the same; hot spots and other differences may indicate problems.

Where it’s done: The camera is portable, so thermography can be done anywhere you can control wind and temperature. But it’s not routine, and many practices don’t have the equipment. “Thermography has gone in and out of vogue several times,” says Dr. Allen. He uses it in his practice but says, “As other technologies have grown up, there’s less need for it now.”

Advantages: Thermography is non-invasive and doesn’t require sedation. The camera is at least ten times more sensitive to heat than the human hand, so it picks up minute temperature differences that could be missed in a physical exam.

Limitations: Many things affect surface heat patterns—whether an area is clipped or wet, whether a leg was wrapped or treated with liniment, whether the horse is standing with sunlight or a cold breeze on one side. “It takes training to read a thermal image, to know what questions it can answer and to understand the limitations,” Dr Allen says.

Thermography has to be combined with other diagnostic methods. “It’s useful for a tendon recheck along with ultrasound or to check for areas of soft-tissue inflammation when a bone scan is negative,” he says. “But while it’s accurate on heat, it’s not specific on the issue—and you can’t diagnose a problem based just on heat.

Cost: About $100 to $200.

Now, The Hard Part

As challenging as it can be to diagnose a lameness, the biggest challenge comes after that. “Suppose you image the fetlock in any or all of these ways, and you see abnormalities. You diagnose a tear in a branch of the suspensory ligament. The hard question is, what does that mean for the horse? If he’s an upper-level event horse, does it mean that his career is over? Or can he return to competition with treatment, and if so what treatment?”

Many people would say an injury like this would end any hope of future events. But, Dr. Allen says, “The horse is a wonderful educational tool. We compile studies that look at the results of actual cases, and they show what conditions can be successfully treated and what treatments work. The evidence shows that many of these horses can return to competition.”

Diagnosis: Sticker Shock

Some lameness problems are clear. If there’s heat and swelling in a tendon, there’s probably an injury there, and your vet will use ultrasound to assess it. When the situation isn’t so obvious, it may take several different approaches to find out what’s making your horse lame. Radiographs, ultrasound, a bone scan or MRI, all on top of a lameness exam with multiple nerve blocks—before you know it, the bills could top $3,000 before treatment begins.

“In the old days imaging was limited to radiographs on film, and it didn’t cost a lot,” Kent Allen, DVM, says. Today’s high-tech imaging tools provide a much better understanding of lameness problems, but the cost is higher.” Even traditional methods are more costly. “Radiographs have close to doubled in cost because the initial investment in digital equipment is high. Old film units cost $15,000 to $20, 000; new digital equipment costs $50,000 to $100,000,” he says. The cost of ultrasound also has risen (although not as dramatically as the cost of X-rays) as veterinarians invest in new equipment and training courses.

The veterinarian and the horse owner can work together to keep costs in line, Dr. Allen says: “Part of the clinician’s job is to do a running assessment of the cost/benefit ratio for the horse and the owner. One nerve block may make sense, but for a lameness that’s hard to pin down multiple nerve blocks and treatments over time may cost more than nuclear scintigraphy. The clinician has to think of the most efficient way to get to the root of the problem and return the horse to work.”

At Virginia Equine Imaging, located near Middleburg in The Plains, Virginia, Kent Allen, DVM, specializes in lameness, sports medicine, pre-purchase exams and state-of-the-art diagnostic imaging. He is also vice president of the International Society of Equine Locomotor Pathology, which provides advanced education for practitioners.

Dr. Allen chairs the United States Equestrian Federation Veterinary Committee and its Drugs and Medications Committee and is a veterinary adviser for the USEF Eventing Team. He also serves on the List Committee of the International Equestrian Federation (FEI) and is the head FEI veterinarian for the United States. Previously he coordinated veterinary services at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games and the 2010 World Equestrian Games in Lexington and served as FEI Foreign Veterinary Delegate at the 2000 Sydney and 2012 London Olympic Games.

This article originally appeared in the January 2014 issue of

Practical Horseman.