You have trained tirelessly and the day of the show arrives. Both you and your horse are fit and ready, you strap on your helmet, buckle your safety vest, strap your medical information to your arm and set out on course. You have done all the things riders do to stay safe in a sport that is inherently risky. But what if you have a fall on course? Who is responding? What are their qualifications? How long will it take to transport you to the nearest capable facility?

In the realm of all the things we consider before a show, medical coverage at the show is probably at the bottom of your list. However, appropriate treatment for you and your horse are necessary in the case of an emergency and can have a significant impact on outcome. There are usually posted contact numbers for the on-site veterinarian and farrier, but not necessarily for the medical personnel. Medical coverage at shows is a significant part of the cost of running a show. It may be cost prohibitive for a small local schooling show to employ a paramedic on site. Many shows run without on-site coverage at all. Emergencies are covered with a call to 911.

See also: Eventing’s Quest for a Safer Sport

This is where the expectation and the reality collide. I have been participating in recognized horse trials and schooling horse shows for the last 16 years. It never occurred to me to ask if a paramedic was on grounds, or to ask to see a safety response plan for the show. For the last 5 years, I have had the opportunity to work as Safety Coordinator for the Carolina Horse Park, and I have learned an enormous amount about what it takes to run the behind-the-scenes emergency coverage. I have also seen firsthand when expectations of response times or care are not met. If one EMT is covering 18 acres of show grounds for a schooling day, the response time can be significant if the fall occurs at another area in the park. Yet, the expectation is that emergency personnel should be responding almost immediately.

First, let’s look at the tiers of EMS (emergency medical services) response. There are four levels of EMS in this country. EMR, emergency medical responder, is the most basic. This includes firefighters and is the first level of response to a scene before arrival of an ambulance. EMRs can provide oxygen, check vital signs, perform CPR, use an AED, splint a fracture,and control bleeding with wound care and tourniquet placement. EMTs can perform the above procedures, and in addition, insert blind airway control devices. They can administer Tylenol, Motrin, glucose and Epinephrine auto injectors. Level three is an Advanced EMT who functions between an EMT and paramedic. Paramedics are the most advanced level and can perform advanced intubation (placement of a breathing tube into the airway), EKG acquisition and interpretation, cardioversion and pacing, IV fluid administration, and narcotic and benzodiazepine medication administration. As you can see, depending on the level of responder at the show, significant differences exist in treatment options on scene.

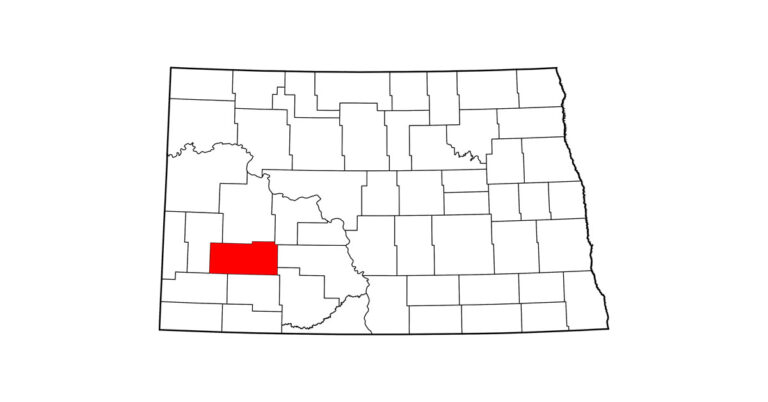

Response time of backup providers varies greatly as well. Consider the jumping competition held in downtown NYC, versus the horse trial located in a small county. One show may be in a system where multiple ambulances are staffed 24 hours with 2 paramedics. A more rural location may have an EMS system in place where one or two ambulances are staffed with only two EMTs, with a paramedic responding secondarily in another vehicle. The national benchmark for response times of all EMS is a provider on scene within 9 minutes 90% of the time. This is an average. Response time in a very rural setting may be upwards of 30 minutes. The American College of Surgeons describes the “Golden hour” of trauma. This is the time period when medical providers have the most opportunity to make a positive impact on overall morbidity and mortality after a significant traumatic injury. While this is not a hard and fast time limit, you can see how a prolonged response time and a prolonged transport time to a trauma center can significantly impact a patient’s outcome.

Hospital capabilities also vary greatly. A Level I trauma center has 24-hour in-house coverage by general surgeons and prompt availability of specialists including orthopedics, neurosurgery, plastic surgery and oral maxillofacial surgery. In comparison, a Level IV trauma center has the capability to provide advanced trauma life support prior to transfer of patients to a hospital with capabilities for a higher level of care. In a significant head injury, evaluation and stabilization at a lower level of care hospital may delay life saving surgical intervention with transfer delays. Transport to the hospital may be by ambulance or expedited by helicopter if a facility further away may be the most appropriate hospital. However, weather and terrain may make it impossible for air transport and can further delay definitive care.

Another challenge to medical response at horse shows is the well-intentioned “Good Samaritan.” If you are a physician or other medical professional at a show, your help is likely very appreciated, but interfering with EMS personnel’s ability to do their job may result in a delay at the scene and an increased time to definite care in a hospital setting. Treatment and stabilization in the field are much different than treatment in an office or hospital setting, and is often best managed by EMS providers trained in pre-hospital trauma care. EMS providers work within a defined set of protocols approved by their medical director. If an outside physician wants to deviate from these protocols and be involved in the care of the patient, they are accepting responsibility for the patient, and must remain with the patient throughout transport and handoff to the receiving hospital physician.

What is the solution? As great as it would be to have maximal medical coverage at all shows, this is cost-prohibitive for many small farms and 5013c organizations. If we cannot set a standard for coverage across the board at recognized and schooling shows in all disciplines, we should encourage transparency for competitors. As riders, it is our responsibility to know what type of coverage is in place, what level of care they provide, what is the average local response time for the area and how long the transport time is to the closest appropriate medical facility. It is helpful to know if the closest hospital has trauma designation, and if not, how far away is the closest trauma center? Is there a place to liaison with a medical helicopter and how will this affect transport times? Pre-event planning before a show looks at all of these details, and show management should be able to provide you with this information. Remember, most of us ride routinely at home without EMS coverage standing by, and while we cannot take all the risk out of our sport, we can make informed choices about where we show, and know what to expect in the event of an emergency.

Amie Collins, MD is a board-certified emergency medicine physician, Certified Safety Coordinator for the U.S. Eventing Association. She’s also an amateur eventer, mother of three and is based in North Carolina.

Sources:

https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/is15aspecialeventsplanning-jamanual.pdf

Advanced Trauma Life Support, American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma, 9 Edition, 2010