Extreme flexion, hyperflexion, overflexion, rollkur or riding low, deep and round—call it what you will, it’s controversial. Debate over this training technique has roiled the dressage world for more than a decade. But hyperflexion isn’t just a dressage issue. Trainers in jumping and other disciplines have also used the technique, and it has implications for the way people ride and train horses generally.

Hyperflexion involves riding or longeing a horse with his neck and poll tightly flexed and the profile of his face behind the vertical. His head may almost touch his chest or his knees or may be turned to one side or the other. Proponents say the technique improves a horse’s ability to lift and round his topline (essential for collected work) while it supples his muscles and encourages more expressive gaits. Critics say it harms the horse.

Who’s right? Now research is providing some answers. In this article we’ll look at the arguments and the data.

Hot Topic

Dressage judge and trainer Anne Gribbons says she first saw the technique at the 1990 World Equestrian Games in Stockholm. “It was used by Nicole Uphoff on her champion Rembrandt in the warm-up,“ says Anne, who has officiated and competed at top levels in the United States and abroad. “This horse was extremely spooky, and I think extreme flexion was used to keep his attention in the schooling area.” Anky van Grunsven of the Netherlands, Isabell Werth of Germany and other famous and skilled riders also adopted the method, and other riders began to copy them. “But if the rider is not so skilled, it can become damaging,” Anne says.

By the mid-1990s it was common to see horses being longed or ridden in hyperflexion during precompetition warm-ups, and critics—including leading trainers and respected veterinarians as well as animal- rights groups—had begun to protest that the method was abusive. The International Equestrian Federation (FEI) set up a working group of about 60 riders, trainers, vets and officials to look into it. “Hyperflexion of the neck is a technique of working/training to provide a degree of longitudinal flexion of the midregion of the neck that cannot be self-maintained by the horse for a prolonged time without welfare implications. There must be an understanding that hyperflexion as a training aid must be used correctly, as the technique can be an abuse when attempted by an inexperienced/unskilled rider/trainer,” the group determined.

Extreme flexion was used by Nicole Uphoff on her champion Rembrandt to help the spooky horse focus. This training technique was soon adopted by other riders, and by the mid-1990s it was a common sight in warm-up rings.

That didn’t settle the issue, though. A furor erupted in 2009 after a video showing Swedish rider Patrik Kittel riding a horse in hyperflexion went viral. At one time, the horse’s tongue slipped into view and appeared blue. Outrage over the “blue-tongue dressage video” led to an FEI investigation that cleared Kittel of any violation but prompted a review of the guidelines.

Many revisions later, the FEI position is nuanced: Hyperflexion—redefined by the group as extreme flexion achieved through “aggressive force”—is unacceptable. But extreme flexion achieved without aggressive force and maintained for no longer than 10 minutes can be a beneficial pre-exercise stretch, the organization states. The key factor for the FEI is not the degree of flexion but how the position is achieved.

“It has been hard to set a policy in writing,” says Anne, who served on the FEI Dressage Committee at the height of the uproar. “It is still a work in progress.” Meanwhile, hyperflexion has become a sort of zombie controversy, refusing to die.

Science Steps In

How does extreme flexion, regardless of how it is achieved, affect the horse? Many researchers have tried to answer that question, focusing on different effects and sometimes reaching conflicting conclusions. In an effort to get the big picture, Uta Koenig von Borstel, PhD, a professor at the University of Gottingen, Germany, led a study of studies—a review of 55 published articles that assessed the effects of different head and neck positions. The results were presented at the 2015 conference of the International Society of Equitation Science, a group that supports research into equine training and welfare.

The review analyzed individual studies for their findings on the physical effects of different head and neck positions and the impact those positions had on the horses’ welfare. It also weighed factors that varied from study to study, such as the horses’ level of training, the quality and design of the study, and the degree and duration of hyperflexion. These studies defined head and neck positions in terms of relative flexion and elevation rather than the rider’s use of force or aggression. Hyperflexion, for most, was any degree of neck flexion that put the horse’s profile behind the vertical.

“There’s unfortunately no consensus in practice on what degree of pressure is considered acceptable or when a pressure becomes force,” Dr. Koenig von Borstel explains. “From a scientific point of view, a good threshold would be the amount of pressure a horse voluntarily accepts, for example, in an attempt to reach a food reward. These values are very commonly exceeded during regular riding and more so when riding horses in strongly flexed postures.”

A resounding 88 percent of the studies reported that hyperflexion adversely affected the horse. Negative effects appeared regardless of how flexion was achieved, how long the horse maintained it or whether the horse had been previously trained in hyperflexion. They included:

- Impaired breathing. Studies showed evidence of airway obstruction during hyperflexion. Flexion narrows the opening of the windpipe at the pharynx, making it harder for air to pass through. The horse can still breathe, but he has to work harder to inhale. Difficulty in breathing was seen as a cause of increased anxiety in these horses.

- Impaired vision. Several studies demonstrated that a horse can’t clearly see where he’s going when his face is tilted toward the ground, another cause of anxiety.

- Damage to the structures of the neck. Increased flexion puts tension on the nuchal ligament, the main ligament of the neck. Some studies suggest this can lead to injuries, especially where the ligament joins the vertebrae of the neck. Over time arthritis can develop in the vertebral joints.

- Stress and anxiety. Horses showed signs of increased stress when ridden or longed in hyperflexion, a number of studies found. The position’s physiological effects (such as impaired breathing and vision) as well as rider interventions (like rein pressure or forceful aids) were cited as causes.

Researchers measured stress in various ways. For example, a study led by Janne Christensen of Aarhus University, Denmark, assessed stress levels through behavioral signs such as head-tossing and physiological changes such as increased levels of the hormone cortisol in saliva. The subjects—15 dressage horses who were already accustomed to work in hyperflexion—were ridden by their usual riders in a set 10-minute program in a loose frame, in a competition frame (nose at or near vertical) and in hyperflexion. The horses showed more head-tossing during hyperflexion and higher cortisol levels immediately afterward.

Horses may also experience harmful effects from lesser degrees of flexion or rein contact, some research suggests. Most of the studies that Dr. Koenig von Borstel reviewed were not designed to look at the effects of gradually increasing flexion, she says. “But in the meta-analysis, when looking across studies with different degrees of flexion, it seemed to be the case that the more flexion, the more negative effects were observed.”

Hyperflexion and Performance

As a training tool, hyperflexion is said to encourage the horse to lift his back, stretch and supple important muscles and (in so doing) improve his gaits and performance. In the studies she reviewed, the evidence was mixed. About a quarter of the studies found some benefits from hyperflexion while almost the same number found detrimental effects. The rest were inconclusive. Most of the findings related to these areas:

- Movement (kinematics). Various studies found increased range of motion in the back or limbs when horses worked in hyperflexion; some showed that step length decreased and the time it took to complete the stride increased. The changes were mostly limited to specific gaits or were observed only when a horse worked without a rider.

- Workload. Some studies suggested that horses generally worked harder in hyperflexion, based on their heart rates and measurements of lactate concentrations in blood.

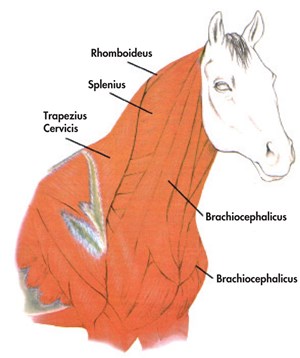

- Muscle activity. Research that tracked the electrical activity of different neck muscles showed that the muscles of the topline (splenius, trapezius) were most active when the horse’s profile was in front of the vertical. In hyperflexion, a major muscle of the lower neck (brachiocephalicus) was more active.

- Performance. Depending on the study and the horse’s level of training, dressage horses’ scores were lower, higher or no different when hyperflexion was part of their warm-up or training. Young horses were judged to be more rideable in hyperflexion, possibly because they appeared submissive.

The review’s conclusion? Negative effects by far outweigh any presumed benefits. Dr. Koenig von Borstel believes further research isn’t needed. “The available data clearly shows that hyperflexion is bad, so there is no good reason to subject more horses to such treatments,” she says.

What about the athletic benefits of muscle stretching? The FEI guidelines for dressage stewards, who are charged with monitoring warm-up rings, classify “low, deep and round” and other extreme neck flexions to be forms of warm-up stretching. “The use of correctly executed stretching techniques, both before and after training and competition, is recognized as an important and long-established practice in almost every physical sport. In equestrian sport it is used for the on-going suppleness and health of the equine athletes,” the guidelines state.

But sports-medicine experts have recently questioned the benefits of pre-exercise muscle stretches, particularly the type called static stretches, for human athletes. In the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, Phil Page, PT, PhD, a conditioning specialist who teaches at Louisiana State University and Tulane Medical School, explains that in static stretching a specific position is held briefly (think seconds, not minutes) and released. This can be done passively (by a partner) or actively (by the athlete). Dynamic stretching involves moving a limb through its full range of motion. Both types can increase range of motion, but pre-exercise static stretching has been shown to reduce muscle strength and performance in running and jumping. (The FEI guidelines use some terms differently—they call a stretch “static” when done at the halt and “dynamic” if the horse is in motion.)

“Pre-exercise muscle stretches are not recommended for horses who must produce high levels of muscle strength or power,” says Hilary Clayton, BVMS, DACVSMR, PhD, professor emerita at Michigan State University and a consultant on horsesport science. Dr. Clayton, who has done extensive research on equine biomechanics, advocates core training exercises that differ from hyperflexion in goals and methods. “The purpose of core training exercises is not to stretch the neck muscles but rather to activate the deep stabilizing muscles that protect the [spinal] joints from injury. In this regard they are more akin to Pilates than to stretches,” she says. The core exercises include “carrot stretches,” in which the horse moves his nose toward his chest, knees, front fetlocks, girth or hocks to reach a carrot or some other bait. They’re done before exercise begins to ensure that the deep stabilizing muscles are activated, Dr. Clayton says.

“We do the carrot stretches when the horse is standing rather than in motion because the neck is not meant to undergo large ranges of motion or to be held in extreme positions during locomotion,” she adds. “We have the horse move the neck through a full range of motion at the halt with the objective of activating and strengthening the deep stabilizing muscles in a variety of positions.” Positions are held for only a few seconds; then the muscles are allowed to relax before the exercise is repeated. “Holding an unnatural position for a prolonged period of time is not good for the horse,” she notes.

Welfare First

After its 2015 conference, ISES issued a position statement that said, in part: “Riders, trainers and sports officials must be aware of the gradual effect of flexion on welfare and ensure that head and neck postures do not compromise physiological or psychological function. Maintaining an open airway and ensuring the horse is self-maintaining the posture (rather than it being enforced by the rider/trainer and/or tack or equipment) are essential.”

Are the current FEI guidelines, which permit extreme flexion obtained by “unforced and nonaggressive means,” sufficient to guard against abuse?

“Riding is all based on negative reinforcement—the application of pressure by reins, legs, spurs, whip and the rider’s weight until the horse gives the desired response, at which point the pressure is relieved—so as of yet, I have not seen any sport rider working without pressure,” says Dr. Koenig von Borstel. “The neck conformation of most horses does not allow them to maintain extreme flexion for any length of time entirely on their own so a certain degree of permanent pressure by the rider is necessary. Clearly, this is against the doctrines of dressage that aim at maximizing lightness and self-carriage.”

Anne Gribbons says the central question is how force should be measured. “It would be nice to think that a horse would willingly perform a Grand Prix with the rider doing nothing, but the fact is that there is always a degree of tension and force. When does it cross the line? Is it when the rider grabs the reins and kicks? Is it when the horse looks tense or frightened? But some horses are by nature tenser than others. In the guidelines we tried to be as specific as possible, but it’s still a subjective call,” she says.

“I am thrilled to say that hyperflexion never caught on as widely in the United States as it did in Europe. Most Americans don’t like to train this way, using hyperflexion as a way to get submission,” Anne adds. Used for very short periods, she says the technique may be helpful in a few limited situations—for a horse who’s extremely unfocused or can’t deal with his surroundings or for a young horse who insists on hollowing his back “just to get the back up for a moment so he gets the idea that he can do that.”

Abuses should be addressed through rules and supervision, Anne believes. She says that through stewards’ clinics and other forums, officials are learning to spot signs of tension—changes in breathing, sweating, a panicked look in the horse’s eyes. “We want horses that are happy in their work. We have to protect them. We can regulate actions at shows, but at home it’s up to riders and trainers.”

Mechanics of Flexion

Most people think of flexion in terms of a horse’s head and neck position, but flexion can affect his entire body and way of going. That’s because the neck is an extension of the spine, and it’s linked closely with the back in a finely tuned system of support.

Bones: Like the rest of the bones that form the spinal column, the seven cervical (neck) vertebrae enclose and protect the spinal cord. Each bone is uniquely designed for its site and function. The atlas vertebra, first in line, is shaped to allow the horse to nod his head or turn it to the side to produce, respectively, direct flexion and lateral flexion at the poll. The axis vertebra, next up, is shaped to allow twisting or tilting of the head. The rest of the cervical vertebrae form a chain that dips down to the base of the neck before turning to join the rest of the spine below the withers.

Joints: Joints between the vertebrae allow the neck to be flexed, bent and twisted, but their individual range of motion is limited. Moreover, “Horses choose to move and position their necks using the joints at the base of the neck and the poll rather than those in the midneck, though the rounding of the muscles on top of the neck can be misleading in this regard,” says Hilary Clayton. “In the low, deep and round position most of the flexion is at the base of the neck and there is actually surprisingly little flexion in the mid-neck.”

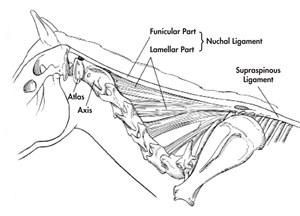

Ligaments: Tough, stretchy ligaments support the spinal column. Short ligaments between the vertebrae hold the bones in place. The long nuchal ligament runs from the back of the skull to the withers with sheets of elastic tissue stretching from the neck vertebrae to the body of the ligament. At the withers it joins the supraspinous ligament, which supports the back. These ligaments work together to hold the vertebrae in place and control the amount of movement when the horse flexes, extends or bends his neck. “When the neck is deeply flexed, tension in the nuchal ligament pulls the withers forward and helps to keep the back rounded in the area beneath the saddle,” Dr. Clayton says.

Muscles: Most of the neck is muscle. Short, deep muscles help stabilize the vertebrae. Long muscles, anchored at strategic points on the bones and ligaments, contract to raise, lower, turn, bend, flex and extend the neck and, in some cases, move the front limbs forward. They include the trapezius, rhomboideus, splenius and semispinalis muscles above and alongside the spine and the brachiocephalicus below.

This article originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of Practical Horseman.