Amino acids are a hot topic in today’s equine nutrition. They are the vital biological building blocks that link together in the horse’s body to create proteins, which form everything from muscle tissue to organ tissue as well as enzymes, hormones and antibodies. “Aside from water, protein is the most abundant molecule in the body,” says Middle Tennessee State University associate professor Holly Spooner, PhD. “All tissue is made from protein. But it is perhaps the most misunderstood essential nutrient.”

Horse owners tend to focus on crude protein, which, she explains, is actually just an estimate of the amount of protein in a feed product based on how much nitrogen is present (since nitrogen is much more abundant in protein than in other nutrients). “But that doesn’t exactly tell the whole story,” Dr. Spooner says. Quality matters more than quantity when it comes to protein in your horse’s diet—and quality is determined, in part, by which amino acids are present in his food.

All grasses, grains and hays have a certain amount of protein in them. When it arrives in your horse’s stomach and small intestine, enzymes break it down into its amino-acid components. His body then puts these building blocks together in new configurations to make whatever it needs at the moment—for example, new tissue for muscles or vital organs.

Horses, like all mammals, use only about 22 of the more than 500 amino acids that exist on earth. Their bodies manufacture 12 of those 22, so we need to provide the other 10 “essential” amino acids through food: lysine, methionine, arginine, histidine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, leucine and isoleucine.

Each protein a horse’s body makes has a unique code, a formula dictating how a specific sequence of amino acids should be strung together. Some proteins consist of just a few amino acids; others are chains of thousands. If one amino acid in a particular protein’s formula isn’t available, the body can’t substitute it with a different amino acid, so that protein can’t be made.

“It’s like putting together Legos,” Dr. Spooner says. “The individual blocks are like amino acids. If your plan calls for six red Lego blocks and you don’t have six red Legos, you can’t keep building. It doesn’t matter that you have 150 blue Legos or 200 green Legos.”

In this scenario, the red Lego represents what is known as a “limiting amino acid.” How much you have of it limits how much protein you can build. In horses, scientists know that lysine is the most important limiting amino acid. They’ve estimated how much lysine horses need in their diets, but there is very little research about how much of each of the other amino acids they require. This is because horses are more labor-intensive to study and the benefits are harder to define than in other species, such as pigs and chickens.

While we wait for equine science to catch up, much of what we do know comes from human-nutrition research. For example, as with humans, although amino acids play many different roles in the horse’s body, their primary purpose is to build protein. “Anything beyond that is going to be a relatively small portion of that amino acid,” says University of Kentucky associate professor of equine science Kristine Urschel, PhD. “People get bogged down with some of the special uses for amino acids—such as tryptophan having a calming effect—when, first and foremost, amino acids are used to make protein.”

How to Make More Muscle

So let’s focus on protein—more specifically, muscle protein. Muscle is about 70 percent water and 20 percent protein. The other 10 percent includes fat, vitamins, minerals and glycogen (the muscle’s main energy source). The size of a muscle is largely determined by how much protein it contains. And this, it turns out, is a more fluid system than you might realize. Dr. Urschel explains, “It’s not that a muscle protein gets made and then stays there forever. It’s constantly in the process of being broken down and then remade, which allows the animal to be able to adapt to changing conditions.” For example, if a horse has a chronic disease, he may need to repurpose some of his muscle protein for a different function in the immune system to battle the disease.

When a horse exercises, that exertion causes some of his muscle protein to break down. His body then replaces and adds to that muscle by synthesizing new protein. But building bigger, better muscles isn’t just a matter of feeding your horse plenty of amino acids, says Dr. Urschel. “That’s like a human bodybuilder who thinks he can sit all day eating steak and get lots of big muscles. You’re not going to get, say, the performance-level dressage horse topline if those muscles are never exercised to stimulate them.” Building new muscle, she says, requires a combination of high-quality protein and a good exercise program, which stimulates protein synthesis at a cellular level. “Neither one can do it on its own.”

How Much is Enough?

Each individual horse’s protein requirements depend on how much new protein his body needs to make. If he is growing, he’ll obviously need plenty of protein to build new tissue throughout his body. If he is exercising strenuously, he’ll need new protein to replace and add to the broken-down proteins in his muscles. He’ll also need to replace the proteins and amino acids that he loses through sweat and will need extra protein to maintain the larger lean body mass that results from all this exercise.

The National Research Council’s publication “Nutrient Requirements of Horses” lists the minimum amount of crude protein horses need at different stages of life. It also recommends a minimum amount of lysine for each case. You can plug different body weights, ages and occupations (broodmare, working horse, etc.) into the NRC’s handy online calculator to find your horse’s exact requirements. For example, it says that a 1,100-pound adult horse in moderate work (exercising four to five hours a week) requires 768 grams of daily protein, 33 of which should be lysine. To learn how to translate these amounts into your horse’s daily hay and grain rations, consult your local extension agent or check out the resources in the sidebar, “Where Can I Learn More?”

What happens if your horse doesn’t get all the amino acids he needs? Common signs include weight loss, poor hair and hoof growth, retarded growth in youngsters and lost fetuses and decreased milk production in broodmares. “But these conditions are rather uncommon in a horse with a normal weight receiving adequate feed intake,” says Dr. Spooner. “In the U.S., we more commonly see protein being fed in excess than we see protein deficiencies, except maybe in the case of young, growing horses.” In fact, she says, most adult horses on a maintenance regimen (doing minimal or no exercise) get all the protein they need from forage—grass and hay—alone.

The horses who need the most extra protein are lactating mares, who are helping their babies grow new tissue while supporting their own bodies’ protein needs. The next protein-needy horses are weanlings, yearlings and horses in heavy exercise. However, even horses in intense training, like racehorses and upper-level three-day event horses, need far less protein than lactating mares. In fact, because their diets are generally so calorie-dense to meet their higher energy needs, performance horses typically get more protein than necessary.

How to Interpret Feed Labels

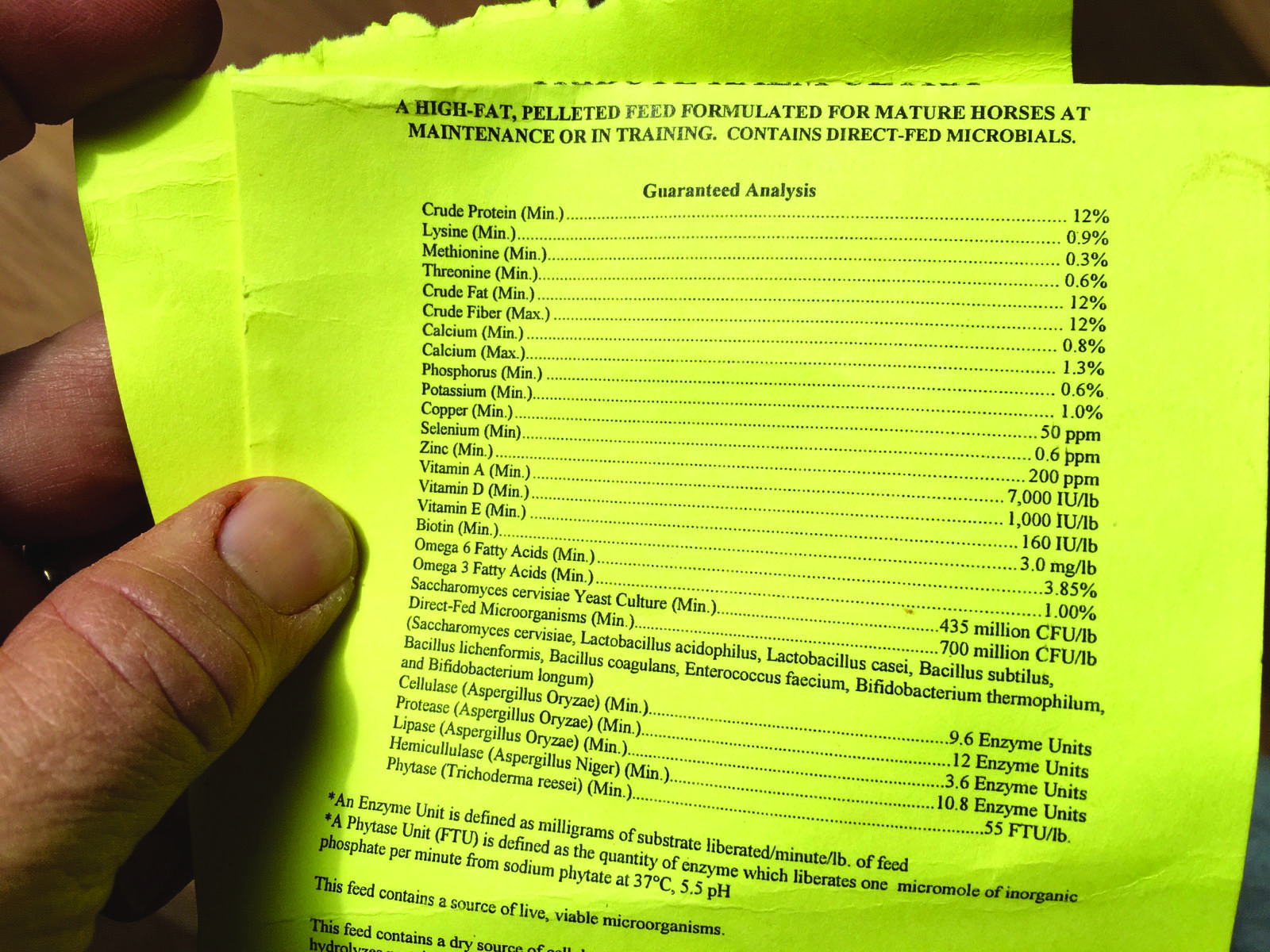

In general, both our experts agree that most horses get all the protein they need from a combination of good-quality forage and a suitable amount of concentrate designed for their age and lifestyle. However, says Dr. Spooner, the crude protein percentage you see on a feed label “really isn’t what we should be focusing our attention on. All proteins are not created equal. If we’re meeting the horse’s protein requirement with poor-quality protein in terms of the amino-acid profile, we could still have a horse who is unable to build the protein that he needs.”

So what is good-quality protein? In forage, it usually means immature, leafy hay rather than old, stemmy hay. Grass hays are generally between about 6 and 10 percent protein, whereas legume hays, like alfalfa and clover, can be 15 percent or higher. Whatever hay you’re feeding, Dr. Spooner highly recommends having samples of it tested “because it can be very deceiving. For instance, we have a relatively immature prairie-grass hay here at the university that often comes in with a protein level of 4 to 6 percent, which is pretty low compared to what most people might expect.”

To further complicate things, researchers have learned that horses’ bodies can’t actually access all the protein they receive in forage. That’s because the plants’ thick cell walls—the fiber—can’t be broken down until the forage arrives in the large intestine, also known as the hindgut. But the enzymes in charge of breaking proteins down into amino acids are located in the foregut: the stomach and small intestine. So, theoretically, by the time the protein from forage is accessible, it may be too late for the body to actually use it. Concentrates, on the other hand, have less fiber, so are more easily digested in the foregut.

“This is another area of research that is super exciting,” says Dr. Urschel. “There’s still a ton that we need to know about it. We know that wild horses have been able to survive and reproduce on almost exclusive forage-type diets. So it’s a bit of a conundrum. I think horses can get at least some amino acids from a good-quality forage, but the lower the fiber in the food, the more digestible in the foregut the protein is.” Having said that, though, she is quick to add, “I still strongly believe that forage should be the backbone of most diets.”

The protein quality in concentrates also depends on the source. For example, cereal grains, such as oats and corn, tend to be low in lysine, whereas legumes and oil seeds, such as soybean meal, have higher lysine levels. Commercial feed companies often add purified forms of amino acids directly to their products to ensure that they reach adequate levels. These are more digestible because they’re already in free amino-acid form. However, Dr. Urschel says, read feed labels carefully. “If you see, say, leucine included in the guaranteed analysis, but not in the ingredient list, all they’ve essentially told you is that leucine was contained in the grains. They haven’t added any additional leucine to it. If it’s in free form, it will be listed separately as an ingredient.”

The four most common free forms of amino acids that you’ll see in an ingredient list are L-lysine, L-threonine, L-tryptophan and DL-methionine. Unfortunately, until more research is conducted, scientists still don’t know what horses’ exact requirements are for each of these amino acids. They do believe, however, that these free forms are the easiest for horses’ bodies to access in their digestive tracts.

Another way to make the amino acids in your horse’s diet more bioavailable is to limit the size of his meals. “Horses often have greater digestibilities when a more reasonable amount of concentrate is fed at any given time,” says Dr. Spooner. She recommends keeping concentrate meals at or below about 0.5 percent of your horse’s body weight (so about 5½ pounds of food for a 1,100-pound horse per meal).

Too Much of a Good Thing

Until we know exactly how much our horses need of each amino acid, why don’t we just give them lots of each? Because the body can’t store amino acids to use later the way it stores carbohydrates and fat. “The body doesn’t store extra protein as muscle,” says Dr. Urschel. Instead, she explains, the liver converts the amino acids that aren’t used immediately into a compound called urea, which is then passed on to the kidneys where it’s filtered and excreted in the urine.

This process requires energy and other additional resources, such as water. The horse’s body can use protein to produce energy as well, but, as Dr. Spooner says, this is “metabolically expensive. It’s not the easiest way for the horse to make energy.” Because it’s much easier to produce energy from carbohydrates and fats, excess protein usually goes unused and thus must be eliminated from the body. This forces the liver and kidneys to work harder as they have to break down and process the protein. “If you’ve ever known anyone who’s done the [low-carb] Atkins Diet, what they’re doing is utilizing protein (and fat) for energy. It’s been known to make people grumpy and they don’t feel well, especially if they try to exercise.

“Excess protein may also hinder performance in the horse,” she continues. “It contributes to what we call acidosis—a lowering of the pH within the horse’s body—which causes him to fatigue faster and not have as good a performance.” Consequently, in recent years, equine nutritionists have begun recommending that performance horses be fed a lower percentage of dietary protein to avoid the protein excesses that often accompany the extra calories they consume.

The acidotic state caused by excess protein can also influence how much calcium is absorbed into the gut of young, growing horses. Researchers believe this might compromise bone growth.

Protein is one of the most expensive ingredients in horse feeds, so feeding your horse extra protein is an unnecessary drain on your budget. Because of its high nitrogen content, it’s also a potential environmental pollutant, not just to nearby land and water but to your horse’s immediate surroundings. When horses excrete excess protein, it produces ammonia gas—the strong smell we all associate with dirty stalls—which, in large quantities, can impact your horse’s respiratory system.

Precision Feeding

So how can you provide the benefits of amino acids without risking these downsides? “There’s a push toward what’s called precision horse feeding, doing a better job of just meeting the requirements, as opposed to throwing the kitchen sink at them,” says Dr. Spooner.

Although the NRC doesn’t yet offer comprehensive amino-acid profiles in its feeding guidelines, researchers continue to study horses’ specific dietary requirements. For example, a recent study found that the amino-acid concentrations in horses’ sweat are different from those in their bloodstreams. They also have a special protein in their sweat that humans don’t have, called latherin, which forms the white lather you see on their coats when they exercise strenuously. This plays an important role in keeping the sweat on the horse’s hair, rather than dripping off his body, thus allowing it to most effectively cool him via evaporation.

The researchers of this study developed a feed supplement to address the unique amino-acid concentrations they’d measured in horses’ sweat. Their results are still preliminary, but anecdotal evidence looks promising. Since horses lose significantly more amino acids through sweat than humans do, this is one area where equine-specific studies will be invaluable.

While the science evolves, both of our experts caution horse owners to be wary of commercial products’ claims that aren’t substantiated with widely published, impartially obtained data. For example, says Dr. Spooner, “There’s a fairly common belief that horses that look poor in their toplines can benefit from amino-acid supplements. But you have to go back and say, ‘Well, what else is being done? Did you put that horse into work? Did you suddenly feed him more in general and maybe what he really needed was just more energy?’ I think the jury’s still out on that to some extent.”

Until we have better science, our experts agree, there’s no harm in experimenting with commercial amino-acid products, for example, with a horse who appears to be receiving an adequate number of calories and the correct type of training to build a good topline but still isn’t doing so. If you decide to supplement your horse’s diet with one of these top dressings, Dr. Urschel recommends following the portion guidelines closely and giving it at least a two-month trial. If you don’t notice an obvious change after two months, your horse was likely already receiving all the amino acids he needed in his regular diet.