In last month’s column (read Part 1 here), I introduced you to several people who guided and shaped my early career, just as your mentors steer your riding progress. My narrative stopped at a point when I had moved to Denver, where I could get lessons from eventing expert Bill Bilwin. It was in Denver that I had my first exposure to another man who would become a life-long mentor—Bertalan de Némethy.

After my father’s death in 1955, Bert was named to succeed him as the U.S. Equestrian Team show-jumping coach, and by the early 1960s he was already an icon in the horse world. In 1961 he conducted a talent search at various locations around the country. Figuring that at age 16 I wasn’t a viable team prospect but would at least get a free lesson out of it, I entered and was the recipient of some of Bert’s typical, no-sugar-coating advice: “Jimmie, you need to start over.” I took his advice to heart and four years later made it to the U.S. Equestrian Team’s headquarters in Gladstone, New Jersey, as a member of the eventing squad. More about that in a minute, but first I want to tell you about Bert.

Memories of Bert

Bert de Némethy joined the Hungarian cavalry after graduating from the Ludovica Military Academy in Budapest. At that time, Hungarian equestrian training was heavily influenced by the German cavalry school at Hanover, which was far more interested in dressage training than the Italian school of the time. Bert studied under such German dressage masters as Otto Lörke, Fritz Stecken and Walter (Bubi) Günther. Although unfamiliar names to the modern horse world, they were forces to be reckoned with in the 1930s.

Bert’s primary interest was show jumping, but he was very proud that he once won the Hungarian National Eventing Championship. (From 1920 to 1940, it was typical of cavalry officers in every country to be adept at more than one discipline.) Bert was named to the 1940 Hungarian Olympic show-jumping team, but World War II prevented his participation. He was able to escape the ravages of war by moving to Denmark and emigrated to the U.S. in the early 1950s.

Another mentor to Bert was a fellow Hungarian cavalry officer, Lt. Col. Agoston d’Endrödy. During his post-WWII exile in England, d’Endrödy wrote a very good book on riding and training, Give Your Horse a Chance. What this book lacks in readability and brevity, it compensates for with informative details and should be on every serious horseman’s bookshelf. Another of d’Endrödy’s students in England was David Somerset, who later became the 11th Duke of Beaufort and owner of the Badminton estate, site of the world-famous event. D’Endrödy had already begun a serious study of the use of gymnastics as a training tool for jumpers, and Bert later told me that he had been the guinea pig for every gymnastic in d’Endrödy’s book. Bert became famous for combining the use of dressage and gymnastics, an approach that accounts for much of his success as a trainer. With his appointment as the U.S. show-jumping coach, he began applying these training techniques to our Olympic squad.

A few years ago, I was discussing Bert’s methods with the late Hugh Wiley, who was a member of some of Bert’s first U.S. teams from 1955 to 1960. Hugh laughed and admitted that a major factor in Bert’s use of gymnastics was the inexperience of Hugh and most of his teammates. “Except for Bill Steinkraus, none of us could find a stride,” he said. “Bert had to keep us in a controlled situation. If he turned us loose the first year or so, we were a disaster.” Bert imposed a curfew on the team while they were traveling in Europe in the 1950s—he wanted them rested for the competitions, not hungover. The show-jumping team at the time—Bill Steinkraus, my brother Warren, Hugh, Frank Chapot and George Morris—were young men and, like Bert, were all single. But as they climbed the stairs after dinner and before curfew, they often saw Bert, slim and elegant in a tuxedo, stepping into the limousine of the local duchess or contessa, out for a night on the town.

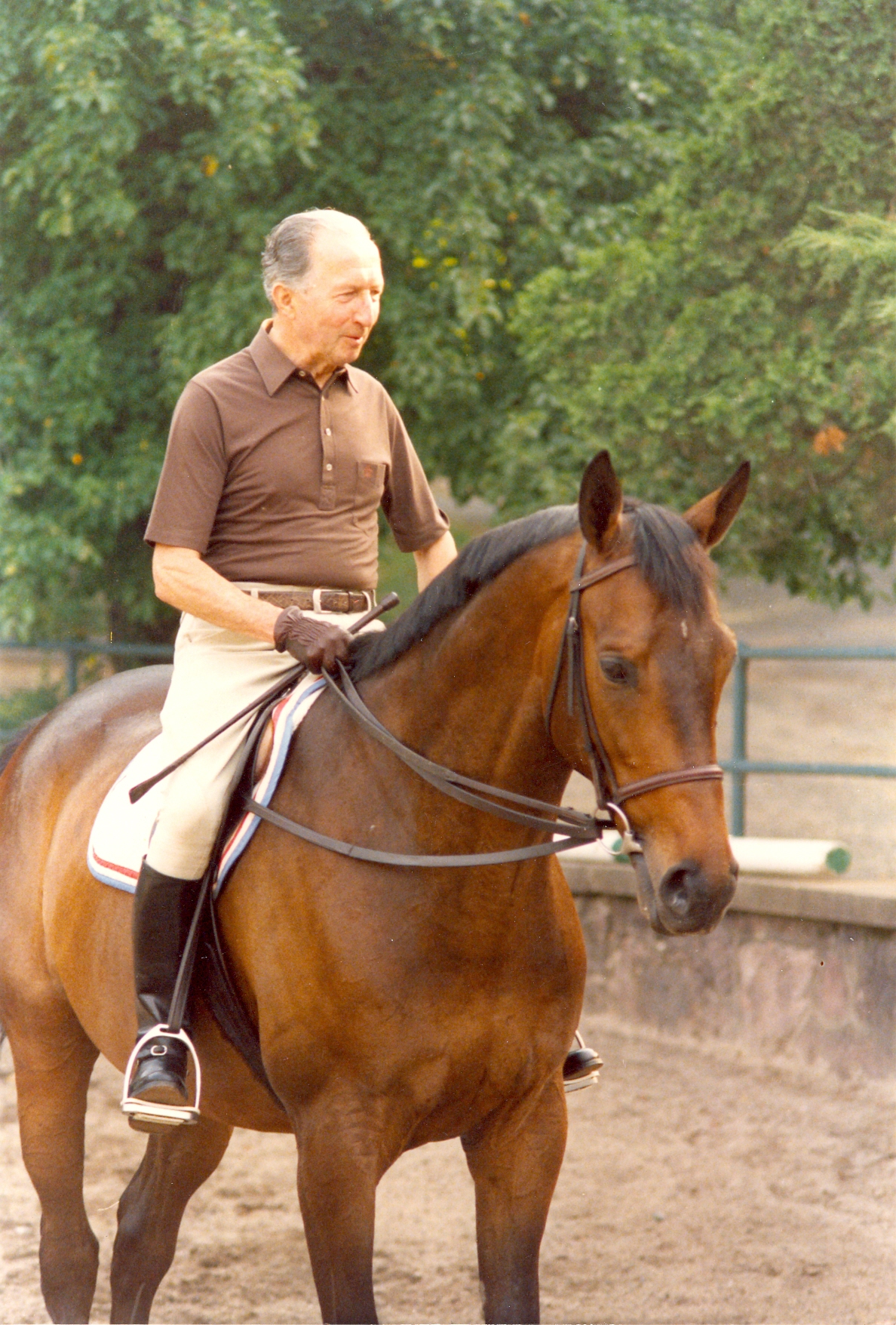

Memory is a funny thing. Bert has been gone for a while now, but in my mind, he is still standing in the main ring at the USET training center in Gladstone. Bert spoke several languages, but he never lost a heavy Hungarian accent and many of his students referred to his speech patterns as “Hunglish.” For example, “Just you are making posting” meant go forward in posting trot. His lessons ran with military precision. Riders were expected to be on time with both horse and rider immaculately turned out. Whatever gymnastics or courses to be used that day were carefully planned and meticulously measured. Occasionally he would get on a problem horse, and the problems would disappear. It quickly became obvious to me that in addition to being a genius trainer, he was a superb rider.

There was nothing fancy or extravagant about Bert’s appearance, but he took great care. No matter how many days he taught or how difficult the weather, he showed up for work the next day immaculately turned out. He always wore either jodhpurs or boots and the “bat-wing” breeches that were fashionable half a century ago. I knew Bert for more than 50 years. He never lowered his standards or his expectations, and he never once showed up with yesterday’s dust on his boots. Never.

Bert had an enormous influence on several generations of American riders. His training in classical dressage enabled him to demonstrate and teach a synthesis of dressage and jumping. His techniques, transformational at the time, are today the generally accepted method of training jumpers around the world.

Because he coached the show jumpers, most of my education from Bert while at Gladstone was through osmosis; a compatriot of his, Stefan von Visy, was the eventing coach. Like Bert, Stefan was a Hungarian cavalry officer and had ridden on the 1936 Olympic eventing team in Berlin. Stefan also was a survivor of WWII and made his living in Austria as a show jumper after the war. He brought the same sense of discipline as Bert and the same attitude toward personal appearance. Stefan jogged a mile before work every day, followed by a cold shower. He was never able to teach me that particular habit. He spoke several languages, but you had to be careful when attempting to apply his instructions literally. During a particularly difficult lesson one day, I discovered that when Stefan said “right,” he meant “left.” Things improved after that.

Although I struggled at the time, in later years I realized that Stefan had taught me a valuable lesson: Not every coach and training system suit every horse and rider. In the long term it is sometimes just as important to learn what does not work for you as to learn what works. Still, I do not consider my time at Gladstone the best possible learning experience. Fortunately, another of the silverbacks who guided my life arrived and proved to be just the right coach at just the right time. By now it was early 1968, and I wanted to go to the Mexico City Olympics that October. The next obvious step in my career was Badminton, and my teammate, Mike Page, suggested I train with Lars Sederholm. In the spring of 1968, I showed up on Lar’s doorstop at his famed Waterstock Training Center in England.

Lars: The Master of Course Walks

If I had to name people who had a significant influence on my career, I would immediately begin with Lars’ name. Although an astute student of riding technique, he based his training very much on the horse. I realized I had been struggling up to this point because using the system I had been taught until now, I had been trying to ride as if my horse were a machine needing continuous supervision and control.

One of Lars’ many sayings that have stayed with me is, “Leave the thinking to him. His head is bigger than yours!” Walking a cross-country course with Lars was to realize you were in the presence of a true master. He could predict your horse’s reaction to various obstacles and describe your actions to handle the problem successfully. By the time you had finished your course walk, you knew how to ride the course. I have led a lot of course walks with a lot of people, but I have never been able to duplicate his ability to translate the problems posed for riders or to have them as mentally ready for the challenges.

Although he was offered the job as coach of the 1968 U.S. eventing Olympic team, Lars’ business in England was too big to leave. Thus another formative influence stepped into my life, this time from out of the past. I had worked in Ireland for a while in 1962, riding and schooling young horses for a famous dealer, Capt. Cyril Harty. While there, I had taken clinics with the coach of the Irish Olympic eventing team, Maj. Joe Lynch. The USET hired Joe on a short-term contract to coach us through the 1968 Olympics. Joe was, quite simply, an Irish character. He had been in the British cavalry most of his life, and during WWII he was a training officer in Scotland preparing troops for combat in North Africa, Sicily and then Italy. Like many of his countrymen, he had a marvelous command of the English language (including a career soldier’s use of profanity and obscenity), an instinctive understanding of horses and a deep appreciation of whisky.

Given some of the more lurid tales he would tell after hours, we suspected that Joe was either about 105 years old or he was more than capable of embellishing a story. His age or his nightly intake could affect his coaching, and I have painful memories of him standing on top of a hill, red-faced and screeching at me in a British accent while obviously forgetting my name, “You theah, come heah, you imbecile, you, YOU …KILKENNY! Come heah!” (He never forgot your horse’s name, but you? Not so much.) Joe was a super horseman and I learned a great deal from him, but he tended to have a short-term fix for your problem rather than a long-term answer to the underlying cause. This may have been a result of the short-term nature of his job and the Olympic pressure he no doubt felt. By now I was developing confidence in my own system, and Joe’s insight helped me in my preparations for the 1970 World Championships at Punchestown, Ireland—but when I got there, I walked the course with Lars Sederholm.

Enter Jack Le Goff

I finished the 1970 World Championships with the bronze individual medal and with my sights already set on the 1972 Olympics. I was in that funny zone that athletes occasionally find—I wasn’t totally arrogant but I was confident of my system and my horse’s capabilities and was not in the mood to change things that were obviously working. This attitude set the stage for the silverback who would change my life and change my system. In early 1971, Jack Le Goff arrived from France as the new coach of the U.S. eventing team. Jack had excellent credentials, having ridden in two Olympics himself (1960 and 1964) and coached the individual gold medalist in the 1968 Olympics. In addition, he had been a successful steeplechase jockey earlier in his career and then spent 10 years with the Cadre Noir, the corps of instructors at the French military equestrian academy.

Like several of my other mentors, Jack was a combat veteran, having been involved in the Algerian War during the early 1960s. It was only in the last few years of his life that he spoke of it to me. He was obviously moved and changed by his experiences and tortured by his memories. An acquaintance of mine who had been a U.S. Marine survived WWII in the Pacific and kept a photo by his shaving mirror of the beach at Iwo Jima, where he could see it every morning. He said he kept it there to remind himself how lucky he was to have one more day and the chance to do something good that day. As another combat survivor, Jack had the same attitude. To him, this meant that he trained and rode intensely all day and then ate, drank, smoked (like a chimney) and partied well into the evening.

I am sad that video had not really been invented while Jack was still riding because you would see an exemplar of the lightness and sensitivity of the classical French system. Jack expected you to solve your own problems, but occasionally he would ride your horse for a few minutes. When he stepped down, you got back onto a different horse. A student once made the mistake of complaining about how difficult her Advanced horse was. In his inimitable French accent, Jack replied, “Oh, daahling, I vould put him in passage and piaffe in one week.” She jumped down, handed the reins to Jack and said, “I bet you a case of champagne you can’t.” A week later she watched, one case of Moët & Chandon poorer, while Jack rode a 20-meter circle around her with the snaffle reins in one hand, a cigarette in the other, alternating between passage and piaffe with invisible aids.

I don’t envy Jack the situation he found when he arrived in 1971. The eventing stables at Gladstone were deserted, and his veteran U.S. riders were running their own programs in various parts of the country. Mike Plumb had already ridden in three of his eventual eight—yes, eight—Olympics. Kevin Freeman and I were Olympic and World Championship veterans and medalists. As far as we were concerned, we had nothing to prove. This attitude guaranteed some spectacular clashes behind the scenes. But as we trained together, Jack gradually realized that he had a few experienced riders who wanted to win as badly as he did, and we realized that Jack was a consummate horseman. Thus began what many refer to as the “Golden Era” of U.S. eventing.

There are many reasons for competitive success—certainly good horses and good riders are a part of it. But Jack was a rare mixture of sensitive horseman, ruthless human disciplinarian, classical dressage training and an uncanny ability to get Thoroughbreds fit for an event while retaining their sanity. (Jack trained during the Classic format era, and most of the horses were Thoroughbreds or near-Thoroughbreds.) Jack developed what is nowadays referred to as an interval system but is actually an intermittent system. He found that if he gave his horses short intervals of rest between periods of exercise, they could tolerate more exercise and yet remain sound.

There is no one reason for success. You cannot point to a single element and say, “That’s the reason.” This is especially true of Jack Le Goff, the most complicated person I have ever known. But you would not be far wrong if you simply said, “Jack was a complete horseman.” He was a genius rider who could train a horse to a high level in dressage, a skill missing in the eventing community when he first arrived in the U.S. His experiences as a steeplechase jockey also gave him unusual insight into working horses at speed. Jack was a severe taskmaster and one of his favorite sayings was, “I am not your friend, I am your coach.” Yet when he was through training for the day, he would once again show you how to take the top off a champagne bottle using a cavalry sabre and let you practice until you, too, learned the skill.

After I had trained a few years with him, Jack remained my coach—but he also became my friend, and we remained so until the end of his life. I know I am a better person for knowing him and indeed for having known all my mentors. The American author Wendell Berry said, “It is not from ourselves that we learn to be better than we are.” All the mentors I have written about in these two columns—these silverbacks—shared their knowledge so generously with me and have enriched my life beyond measure. I cannot tell you of a certain path to success in the horse world, but I can hope that you will find people such as these examples to light that path.

This article was originally published in the September 2017 issue of Practical Horseman.

Interested in reading more about Jack Le Goff? Check out the recently published autobiography called Horses Came First, Second, and Last: My Unapologetic Road to Eventing Gold. Use the code Save20 to get a 20% discount on your order from Equine Network Store!