International rider Richard Spooner likened a jumping round to a pearl necklace. “If it’s a cheap necklace, all the pearls spill out if you break the string. If it’s a good one, there are knots between the pearls so that doesn’t happen.” Rideability, he said, is the knots between the pearls, which are the jumps. Dressed to ride in breeches and boots, Richard delivered a master class, mostly from the ground, with his trademark wit and wisdom. His system for gaining rideability was the focus of the U.S. Hunter Jumper Association’s Emerging Jumper Rider Gold Star clinic, held earlier this year in Thermal, California. Over four days, three groups of mostly young riders progressed from flatwork to gymnastics to a finale of applying their new rideability tools—relaxation, suppleness and responsiveness—over a course. Willingness to “do the work” was a recurring theme.

At the end of each riding session, he told them to “go home and obsess about your horse. At the end of a show day, I try to step outside of myself and look objectively at whatever problem I had that day and think of what flatwork I can do to fix it.” He acknowledged that horses, horsemanship and show jumping can be vexing, so this “obsessing” has to be done without emotion. He framed mistakes, by horses or riders, as instances to be dwelt on only long enough to learn from, then let go.

Suppleness and Relaxation

Most of the riders and horses started Day 1’s flat session tense in their bodies and minds. Richard compared this scenario to the first day of a competition, when the main goal is acclimating yourself and your horse to the new surroundings while creating a relaxed and responsive frame of body and mind in the horse—in essence, suppleness. His main comment was that he wasn’t seeing riders do much to soften up their tense horses. “The whole point of flatwork is a supple and relaxed horse,” he said.

“If you have a course of 15 jumps and a time allowed of 75 seconds, that’s five seconds between each jump. If you are doing flatwork and not asking for some form of a transition, including circles and lateral exercises, every five seconds then you are not preparing yourself to show. Don’t just diddle around. Do the work that you are going to use when you start jumping.”

Riding proactively, instead of waiting for the horse to do something and reacting, was important for everyone, especially those on hot horses. For the tense and spooky horses, Richard told riders to start on a large circle in the middle of the big arena. Being focused on the rider distracts the horse from whatever is going on around him and enables productive flatwork. “Micro-transitions” testing the horse’s responses to forward, back and lateral aids were the order of the day.

Creating a “C” shape in the horse’s body, with him bent around the inside leg and his poll roughly level with the withers, is the key to suppleness and responsiveness. Along with a tucked tummy, lifted back and lowered croup, this is the shape of an engaged topline that maximizes the hindquarters’ power.

The “C” shape is most easily attained on a circle, but Richard advised riding a slight bend even on straightaways. Bend equals control, he said. Using an invisible microbend on a straight approach to a jump helps to maintain the control and frame. “A straight horse is a strong horse”—hence the common advice to turn a bolting horse.

Richard repeatedly coached riders to push, rather than pull, their horses into the inside bend. Using an outside rein to turn results in “instant stiffication,” usually accompanied by the horse sticking his head up in the air. He said this creates the worst possible frame for a jumper: head up, legs down.

Working the horse one side at a time is also a counterpunch to horses who are heavy in the hand. He encouraged “play” through bends to each side—not rough see-sawing, but light rein pressure paired with a strong inside leg. Horses become numb to constant pulling, he said, and a stiff rider produces a stiff horse.

Get Into the Machine

“Get into the machine” was one of Richard’s refrains throughout the clinic. “There’s no way to learn about horses until you really get into them. It’s like trying to fix a car while the engine is running.” This expression translated to riders sitting down and wrapping their legs around their horses’ bodies after each fence to maintain control. “When the horse gets stiff through the body, he locks you out of the machine,” he explained. “The only way back in is through softening to the inside.”

Two other useful tools for getting into the machine are using acceleration and deceleration aids to produce extensions and collection within the trot and canter. The rider’s first step for slowing the pace and rhythm is to exhale: simply let your breath out. Next, he said, “find the tack and sit down”—heavily but not abruptly—and apply knee and thigh pressure while setting the rhythm with your body, visualizing yourself as ice cream melting down around the horse or as a parachute deployed behind a drag-racing car.

Lower leg pressure and a softening hand moving away from the body are the main go-forward cues.

At their subtlest, these aids are the take-and-give cues needed to let the horse know what you want and instantly reward the right response with an ease of pressure. “It’s not when you demand, it’s when you compliment.” Most horses learn happily from frequent “Ich liebe dich” (“I love you” in German) gestures in the form of quick releases of pressure. Richard stressed that “it’s better to ask a million times for one second than one time for a million seconds.”

Applied more emphatically, these same aids are used to race across the finish line in a timed jump-off or rebalance and decelerate for a tight turn. If you practice them frequently enough at home, the changes in your body position for “go forward” and “come back” should be clear to your horse right away.

All horses need to accept and understand the rider’s leg, especially hot and/or cranky horses. These types are often ridden with a timid leg for fear of setting them off. “Then, when you do apply your leg, the horse feels it as a splash of cold water,” Richard said. If your horse balks, spurts away or otherwise resists the leg pressure, keep it on for continued forward motion, using the bend to maintain control. “The hotter the horse, the more I squeeze,” he explained. “Get your leg to feel like warm water to the horse.”

In contrast, he said, overuse of the hand is a symptom of an “illness” plaguing the sport at the lower levels: lack of control. The cure is learning to use everything except a heavy or sharp hand to maintain control. “It’s counterintuitive,” he acknowledged. “You feel the sensation in your hands, so your brain says, ‘Fix it with your hands!’ But you have to retrain your brain to train your horse with your legs. Push, not pull.” Briefly riding two horses during the clinic, Richard walked his talk, putting both through transition-packed paces with very light rein contact.

Ride the Horse, Not the Distance

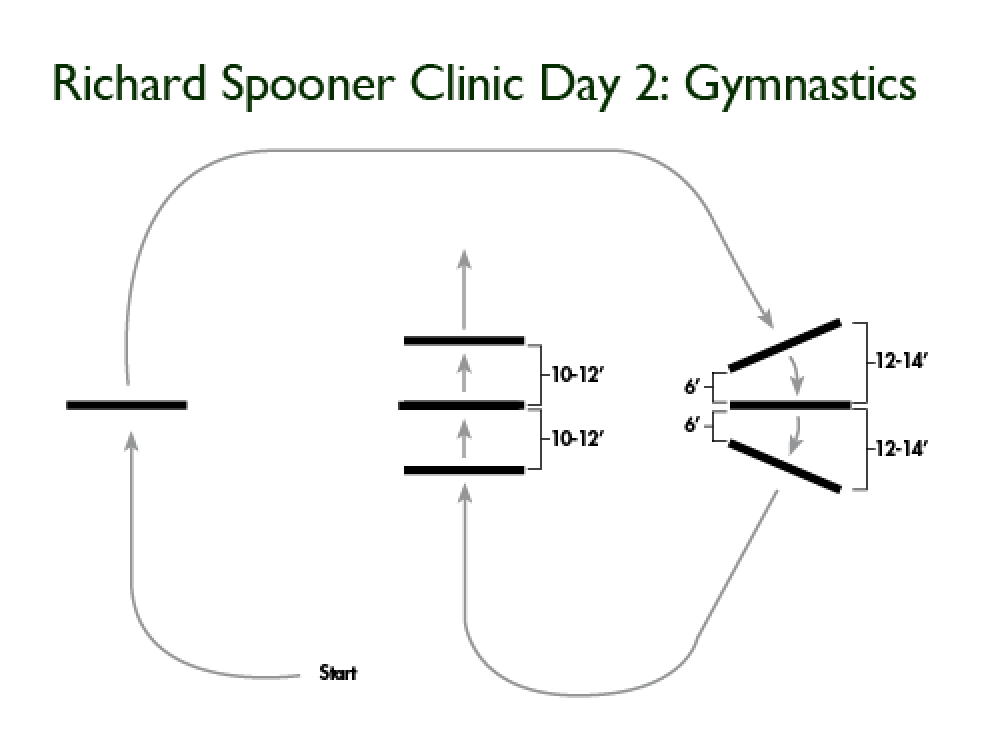

Richard described Day 2 as another flat day, even though the arena was filled with small jumps: two “cartwheel” triple bounces (three verticals set on a curve, with the inside standards 6 feet apart, and the outside standards 12 to 14 feet apart), a straight triple bounce and an oxer, none more than 2 feet high. This setup was similar to what Richard has in his home arena for “flat days when a wooden obstacle just happens to come up now and then.” The jumps were placed in the middle of the ring so they could be ridden on a serpentine track in varying sequences and the exercises emphasized pushing the horse out through each turn and having riders “participate” in all phases of the jump through sustained contact. The cartwheel bounces showed the horse “he can bend and stay soft in the body while jumping.”

Although all the riders returned on Day 2 with more active warm-ups, Richard warned them to avoid abandoning that progress the minute they headed toward a jump. Instead of fixating on finding a distance, he encouraged them to try to manufacture a good distance. “It’s not an Easter egg hunt where you’re saying, ‘Oh, there it is!’ and go get it.” That mentality destroys the soft, supple frame that leads to a good takeoff point arising on its own with the horse in the best frame to make a good jumping effort. “Ride the horse, not the distance,” he said often.

One rider made the common mistake of “letting everything go in search of the distance,” he noted. She then struggled to regain control on landing and through the turn to the next jump. A hard tug on the outside rein stiffened the horse’s frame, preventing him from sighting the next jump early. That can be a grave mistake at the higher levels, Richard said. As a horse approaches a jump, he does a “mathematical equation” of its height, width, angle, etc., to calculate how high he has to jump. The more time he has to do that, the better.

In another case, Richard turned his attention away from a rider before he finished riding the track. “Once I see that he is pushing his horse off the inside leg through the turns and has his horse in the right shape, I can sign off on the project because I know the jumps are going to be right.”

Control Your Body to Control Your Horse

Leaning forward before the jump was a common bad habit Richard sought to correct. “Think of your horse as an extension of your legs,” he said. “You want to get to the jump with your legs, rather than trying to get there with your head first by leaning forward.” When appropriate, he added, the softening cue just before the jump is exhaling and dropping your weight into the saddle—just as it is on the flat—not leaning forward.

The next gymnastic question tested control and rideability. Richard first assigned the easy task of jumping a very short one-stride triple—three fences in a row set apart at one-stride distances of 18 feet. The riders then were asked to gallop to and through a very long one-stride triple (set at 30 feet), then return to the 18-foot triple through a right turn. “You have to let the genie out of the bottle, then find out how much rideability you have. It’s hard to have control at speed and that’s often when the wheels come off.”

This exercise also addressed the common problems of not having the horse in front of the leg and not moving with enough pace to the first jump on course. Riders had to greatly exaggerate both skills to get through the long one-stride successfully. After that, the key was taking full advantage of the sweeping right turn to regain control before the short one-stride triple. “Take advantage of that gift on course,” said Richard of big turns or long stretches between jumps.

Day 3 continued these lessons, combining gymnastics with single course elements riders would face on Day 4. FEI course designer Martin Otto also shared insights on course design and building, using the next day’s course as the example.

Nations Cup Conclusion

On the clinic’s final day, riders applied the previous three days of flat and gymnastic work to a modified two-round Nations Cup, set at heights ranging from 1.10 to 1.35 meters. Savvy veterans serving as chefs d’équipe helped them prepare: 2012 World Cup champion Rich Fellers, 2008 Olympic team gold medalist Will Simpson, international rider Kirsten Coe and DiAnn Langer, U.S. Equestrian Federation Young Rider chef d’équipe.

Immediately after each round, Richard reviewed the rider’s application of what they’d worked on. “Doing the work” between the jumps—tying those knots in the pearl necklaces—was the focus for everybody, and a few mishaps enabled him to bring up additional training topics.

One horse, for example, had two refusals at the one-stride combination, 11 A–B of the 12-effort first round. “You were focused on the jump, but your horse wasn’t,” Richard assessed. “You need to pay more attention to what your horse is doing, rather than to the jump.” He said an extra strong inside leg and rein would have enabled the horse to see the jump sooner, possibly preventing the refusals. “But the real problem I could see from the beginning was this horse had too much energy. You needed to be thinking control, not speed. His distraction is really a symptom. He needed to be at a different energy level. Maybe he should have been longed.”

Several horses balked at a mid-course skinny vertical, prompting Richard to talk about “becoming your horse’s instructor.” He explained that balking and “squatting” on approach to a fence is the horse saying, “I don’t know.” This can be the first step toward losing heart. The rider’s instinct is usually to goose him with leg and spur, go to the crop and generally panic. The better response is to gather him in, take more control and say, “I will show you by explaining it to you with contact.” Richard also recommended thinking of your horse’s body as a Slinky. “You want to put pressure on both ends, not let it spool out.”

Before moving into the jump-off round, he counseled the participants to be “smooth with speed” and minimize the “chaos moments” that often come with quickened heart rates. Across the board, over some parts of the course—in a few cases, all of it—riders minded the knots of their pearl necklaces very well.

Watch the Warm-Up Ring

When Richard Spooner isn’t riding, he’s often watching other riders—and the warm-up ring at major shows is a favorite observation spot. “In Europe, there are often more spectators at the warm-up ring than there are for the grand prix classes in North America.” For him, it’s always a fascinating scene. “Even something as simple as how somebody gets on their horse. Watch [French Olympian] Eric Navet, for example. Every time he gets on, he walks around his horse checking everything, even though he has a staff of top professionals helping him.”

Gold Star Clinics

Held on both coasts, the Gold Star clinics are a new event in the USHJA’s Emerging Jumper Rider program, which is designed to help up-and-coming riders learn a more complex approach to riding and horsemanship so they can build a full toolbox of training techniques. To qualify for a spot in one, a rider must be committed to show jumping’s high performance path.

This article was originally published in the September 2018 issue of Practical Horseman.