When deciding how to pin hunter classes, judges ask themselves, “Which of these horses would I most like to ride?” With rounds lasting only 90 to 120 seconds, there’s not much time to demonstrate that your horse is the answer to that question. From the moment you enter the ring to the moment you leave, your performance must exude ease and confidence. Communication between you and your horse should be nearly invisible. Nothing should distract the judge’s attention from his round. In fact, the best riders seem to melt into the scenery—all you notice is the horse. Exceptional hunter riders allow the horse’s expression to come through so every obstacle he meets is simple, forward and enjoyable to watch.

How do you produce a round like this? By making a fantastic first impression and demonstrating beautifully consistent rhythm from beginning to end as well as smooth turns and balanced takeoffs and landings. I’ll give you tips and exercises to practice at home to achieve these things. This month, I’ll discuss pace and give exercises on how to practice maintaining it to a jump and through a turn to a line. Next month, I’ll share an exercise on how to turn around a fence to jump another fence on a diagonal and another exercise to turn your head while jumping through a grid to improve your ability to look ahead.

Start the Way You Want to Finish

A winning round starts right from your opening canter and first jump. This is not a warm-up or a freebie jump—it counts. Canter the first fence as if you’ve already cantered four jumps. This sets a tone that you plan on doing this round smoothly and with confidence.

The most frequently used symbol on my judge’s card for the first jump in the Adult Amateur division is the notation I make for slow and close. Riders tend to be hesitant and underpaced. As a result, they end up too deep and/or weak to the first jump. This makes me think, “Do they even want to jump that?” If the feeling you’re presenting is, “I’m not sure I want to be out here right now,” then you shouldn’t expect a great score.

Some hesitation comes from nerves. For tips on combating them, see the sidebar, “Keep Your Cool,” below. Some of it is lack of experience. Perhaps the biggest difference between amateurs and professionals is that amateurs “wait until it’s time to go” whereas professionals “go until it’s time to wait.” Professionals are confident going forward to the jumps—even when they have not yet determined a takeoff spot. If you are already going forward and need a small stride increase to get to the jump correctly, it’s available to you. If you need to wait and give your horse an extra fraction of a second to settle the stride, that’s easy to do, too.

However, if you’re overly cautious and don’t go forward to the jump, you won’t have those options. You may see a distance late in the approach and try to attack it. Startled and thrown off balance by this sudden change, your horse will make a mediocre jumping effort and land on the other side disorganized. Worst-case scenario: You approach the jump cautiously and then see the need to slow down even more. At this point even the most athletic horses will struggle to do their job. Without impulsion, straightness and confidence, our kind partners find themselves digging out of holes our backward rides produce right in front of the jump. This can result in an awkward chip, a refusal or crash. Even if the jump isn’t a total failure, you still have created a drastic change in pace, which is a major fault in our sport because of these unsafe scenarios.

Similar errors occur often on single fences with long approaches. For some riders, this is a Pandora’s box. Feeling as if they have too much time and need to be doing something, they get caught up in changing things—sometimes multiple times—whether they are looking for the perfect distance or trying to straighten their horses.

Riders showing in the 2-foot to 3-foot-6 hunter divisions merely need to arrive in the vicinity of a good takeoff spot to give their horses the opportunity to jump a fence well. They don’t need the same precision that riders jumping 4 or 5 feet need. Instead, they should focus on establishing the right rhythm, pace and track, and then relinquish control of the distance.

The following exercises will help you do that. You will need an adjustable horse who is willing to go calmly forward. (Although these exercises are designed primarily for riders jumping at or below 3-foot-6, they’re easy to modify for all levels.)

Homework: Pick up the Pace

Begin by practicing picking up more pace. Get comfortable with the concept of going forward until you see it’s time to do something else, whether that’s calmly and subtly asking your horse to wait or to increase his stride slightly without changing his rhythm. Here’s how:

Place a flowerbox or pole on the ground on a quarterline or on a long approach on a diagonal. The goal is to go from one end of the ring to the other end on a straight track, jumping the obstacle “out of stride”—maintaining the same forward, rhythmic canter the entire way, without making any changes.

As you enter the turn, look where you want to end up. Find something specific to focus on, like a leaf on a tree branch or a knot in the wood of the indoor wall. This is your focal point. The ground pole or flowerbox should just be a part of the straight path to your destination. You can glance at it briefly, but focus primarily on your point beyond the end of the arena. Your body will follow your eye and so will your horse. If he strays from the track, don’t take your eye off of your focal point. Keep looking at that point while using your legs, seat and hands to guide him back on track.

Coming through the turn, go forward. This not only improves your chances of jumping the flowerbox out of stride, but it also helps make your horse straighter. Imagine if you have a loose piece of string on a table in a serpentine-like shape. If I tell you to straighten it by pushing on either side of the string, it will take forever to get it straight. However, if you pull the two ends apart to lengthen the string, it’ll straighten right out. It is the same with your horse. The best way to straighten him is to lengthen him.

Once you’ve established that forward canter, stay on it. Tell yourself that this is no different from any other approach. I hear so many students ask, “What do I do when I don’t know what to do?” Trust that when you don’t see a distance to the pole or flowerbox—whether you’re 20 strides away or two strides away—you have taken care of your pace, rhythm and path. All you have to do is sit up and let the jump come to you. Whatever the outcome, it will be better than a last-minute change coming from panic.

Canter this way over the pole or flowerbox in both directions two or three times. Then go on to other things. Revisit the exercise later in the ride or on another day that week, just to remind yourself about the importance of a consistent pace, path and rhythm. Repeating these consistent approaches will give your “eye”—your ability to judge the distance to a good takeoff spot—a chance to develop. You will never get that chance if you change your canter on every approach.

Make Smooth Turns

Another often-underestimated element in an exceptional hunter round is turns. Done correctly, they make jumping much easier. Done incorrectly, they make jumping much more difficult. If riders turn too early or too late, they usually end up attacking the jump, pulling back on the reins, hoping for more time or trying to move the horse left or right to correct the path belatedly. All of these throw your horse off balance, limiting his ability to jump a square, straight, quality jump.

Maintaining the same pace around turns is challenging for many riders. They canter to the end of the ring, lose the pace on the turn and then try to find the canter again afterward. In a beautifully smooth hunter round, that canter has to be present and accounted for throughout the entire turn.

Another troublesome habit that ruins turns is riding with “laser vision” between your horse’s ears. Riders who do this usually turn first and then look to see where they are. It’s like shifting lanes in a car: You shouldn’t just turn your car and then see if you ended up in the correct lane.

These mistakes are especially common when the approach to the jump involves going around another obstacle. For instance, having to go around an outside line to get to a single jump on the diagonal seems to really play with people’s eyes. Riders tend to wait until they’re past the first obstacle before planning the turn. By then, they have missed the correct turn and end up on the wrong track to the fence. They spend the next several strides correcting that mistake and re-organizing, which often destroys the jump and the flow of the round not to mention confuses the horse.

The solution to turning problems like these sounds simple, but it isn’t always easy: Look before you turn. Get comfortable turning your head to look where you want to end up—before you start your turn—then bringing your horse into line with where your focus is. Remember, your body and your horse will follow your eyes.

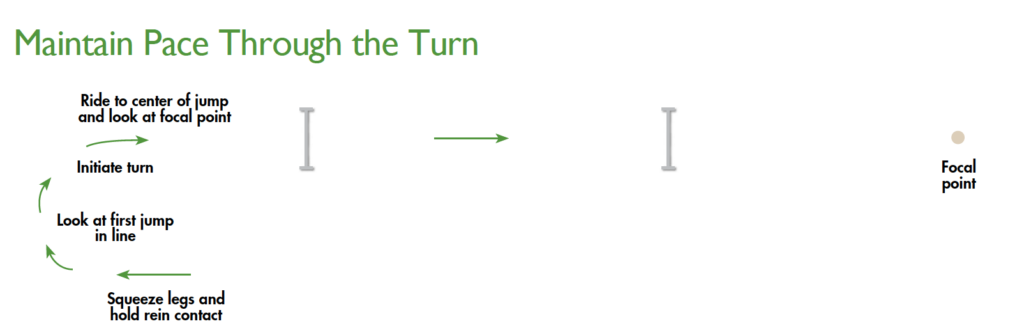

Homework: Maintain Pace Through The Turn

By giving yourself a system to rely on, you can develop quality turns and eliminate erratic and inconsistent approaches from your courses. This next exercise, turning on a line, and the ones I’ll share next month will improve your turns and your ability to look ahead.

Turning on a line builds on the focal-point skills you learned in the previous exercise. Set up two fences in a line down the side of the arena, at least five strides apart (72 to 76 feet, depending on your horse and fence height).

Canter to the end of the ring and squeeze your legs on your horse’s sides while holding enough rein contact to prevent him from going faster. This will engage his hind end with energy and improve his canter. It also will help you maintain the pace through the turn so you have the same canter when you leave it that you had when you entered.

As you canter across the end of the ring, turn your head to look at the first jump in the line. When the second jump comes into view between the standards of the first jump, initiate your turn to the line. As you complete the turn and the two fences line up, ride to the center of each one, focusing your eyes on a point beyond the far end of the ring.

Practice these two exercises until you’re comfortable maintaining your pace to a fence and around a turn to a line. Next month, I’ll give you two more exercises that will build on and enhance those skills.

Keep Your Cool

To begin a round with confidence, make sure you have done your homework, arrived early enough to learn the course and discussed your ride with your trainer. The more times you can get in the show ring, the better your nerves will be. If you are not able to show frequently, find ways to mimic a competition scenario at home or at a friend’s farm. Set up a course in the ring and put a few warm-up jumps in another ring or adjoining paddock. Warm up in this separate area just as you would for a show, then walk into the ring and ride the course as if you were at a horse show with nobody talking you through it. Jump the course just once and tell yourself to live with the results. This “no-second-chances” attitude will help you learn to process your rounds and prepare better for next time.

To perform your best on show day, use the same strategies that schools teach students before tests: Get a good night’s sleep, don’t leave things to the last minute, wake up early enough to eat a good breakfast and stay hydrated. It can be mentally challenging to wait hours for your class at the horse show. Many riders get too nervous to remember to eat or drink, and that really affects their performance. Try to get something in your stomach a few hours before your class, even just small sources of protein, like nuts and grains. Fuel the machine to keep your body performing and your brain firing. If you can, bring a supportive friend to remind you how fortunate you are to have the ability to ride in a horse show. This is all supposed to be fun! Afterward, assess your day as a stepping-stone in a long journey, not the end result.

Practical Horseman thanks Lynn Ellen Rice for providing the facility and horse for the photos in this article.

From IHSA to A-Circuit

Hunter rider, trainer and U.S. Equestrian Federation ‘R’ judge Tom Brennan began his successful career as a member of Stonehill College’s equestrian team. While earning his degree in psychology, he won two individual championship titles at the Intercollegiate Horse Shows Association Nationals and captained his team to the IHSA team championship title in 2002–03. He then joined Tony Workman’s training business, Winter Hill Farm, in Hillsboro, Virginia, as a groom and worked his way up to his current co-trainer position. Along the way, clients such as Lynn Rice helped to partner him with talented horses in the show ring. He qualified for Indoors for the first time on Dividend, then rode Gramercy Park and Purple Heart to multiple major championships. In 2012, Gramercy Park was named the USHJA World Championship Hunter Rider Program Hunter of the Year and Tom was named the WCHR National Emerging Professional Champion.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Practical Horseman.