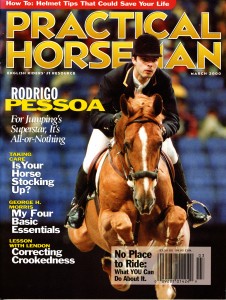

This article on Brazilian show jumping star Rodrigo Pessoa originally appeared in the March 2000 issue of Practical Horseman magazine. Rodrigo Pessoa has added many show jumping titles to his sum since then, including an individual win in the team show jumping finals at the 2010 World Equestrian Games, show jumping team gold at the 2007 Pan American Games and much more. Read about Rodrigo Pessoa’s earlier career in this article about the show jumping star.

At only 27 years old, he has nearly done it all. Brazilian show jumping star Rodrigo Pessoa, two-time Olympian, World Equestrian Games gold medalist and winner of the 1998 and 1999 World Cup Finals in show jumping, could earn his third straight World Cup Show Jumping title this spring in Las Vegas. An all-or-nothing competitor, he’s breathed the rarefied dust of the world’s top equestrian venues—and absorbed a world-famous father’s dreams—since before he could see over the schooling-ring rail.

Rodrigo says he looks forward to his first visit to Nevada (“Is it like the Wild, Wild West?” he jokes dutifully) and a historic chance to best the three elite riders who’ve won two consecutive World Cup titles in the competition’s 25-year existence. But although the upcoming Final has seized the imagination of much of the equestrian world, it’s not his main target in 2000. Having realized one cherished goal by winning the gold at the 1998 World Equestrian Games, he has hopes of beginning the new millennium with an Olympic gold medal. This, he feels, is an achievement that would reward his family’s two generations of effort in the sport.

The goal is a natural for this super-talent. True, he’s had some advantages, his meteoric path to the top smoothed by a world-class support system; but on the way he’s had to overcome unique pressures and challenges. Yet a Sydney gold could also leave him no new worlds to conquer at a stage in life when most riders are still building their careers.

Catching ‘The Horse Virus’

Rodrigo traces the genesis of his own amazing career back 35 years. That was when his father, Brazilian jumper rider Nelson (Necco) Pessoa, relocated to Europe with a string of horses.

Based first in France, then in Belgium, Nelson worked hard at success. He’s ridden in every World Championship. He competed in five Olympics and four Pan American Games. Twice he almost won the World Cup Finals, finishing second in 1984 and 1991. And from the time Rodrigo, his only child, was a pixie-faced youngster with a thick shock of black hair, Nelson took the boy along to shows whenever possible.

“My father didn’t get to see me much because he was traveling a lot, so taking me to shows was a way for us to spend time together,” Rodrigo says. “And he wanted to see if the horse virus and the competition virus would catch me so young and they did.”

Riding from about age 5 (sometimes on a pony that Nelson took along to the shows), Rodrigo got his competitive start in the pony jumpers. “It’s just whoever is the fastest, wins. I competed in all the divisions.” Successful at the national level, Rodrigo says he was less competitive when he began riding large ponies at international shows at about age 12. As the son of one of Europe’s best-known riders, he was increasingly aware that “a lot of people were watching. It was stressful.”

During this watershed period, as a test of whether Rodrigo’s “horse virus” was perhaps cured, his parents encouraged him to put riding aside for a while. “For almost a year I tried many different sports: soccer, swimming, tennis, basketball, judo. but I didn’t find the same pleasure in any other sport as I did in riding.”

‘I Was His Shadow’

Back in the saddle, Rodrigo found a new seriousness of purpose and with it, some new problems.

First, there was the baggage that comes with parents teaching kids—even when the parent is a coach as gifted as Nelson and the son is a student as motivated and talented as Rodrigo. Nelson “can explain everything easily and clearly, with simple words and good examples,” says Rodrigo of his father’s teaching style. “But he’s very hard on any student that he feels really wants to learn something and he was even harder on me. He knew everything, and I thought I knew everything as well. So we had some big fights.”

For instance, there was the hand-position thing. “My father was always saying, ‘Bring your hands up.’ Because if you have your hands too low, you cannot bend your elbows, so you have no contact with the horse’s mouth. It took me a while to understand this” and to outgrow youthful resentment: “When you have a strong character, it’s hard to accept that you’re wrong and should do it the other way. You get sick of someone telling you to bring your hands up,” he laughs. “And sometimes it might be a little bit of a provocation that you do, to see if the person is still watching with the same attention.”

Second, public scrutiny intensified once Rodrigo began riding horses in junior jumping competitions and especially when, in 1989, he began competing in international classes. “I was definitely in my father’s shadow. There was a lot of comparison, a lot of pressure, a lot of unfair critics.” Nelson’s name and his horses opened doors for his son, but there was a down side. “If you do well, people say, ‘Well, what do you expect?’ But if you do badly, they say, ‘I don’t understand how he doesn’t do well with such a father—it’s unacceptable!'”

Another perspective on Rodrigo’s early career comes from US grand prix star Katie Monahan Prudent, for years a regular competitor at top European shows, who sees yet another down side: “Rodrigo has had a lot of great experience at a young age, which is very important. But the road to success usually entails a lot of struggle that teaches you to deal with hard times. With someone as great as Nelson orchestrating everything for him, there couldn’t be much struggle. When Rodrigo does have hard times at some point in life, I think it will be more difficult for him to cope.”

‘The Horse That Put Me on the Map’

Rodrigo started his adult career in 1989 on German-bred Imperial, a horse Nelson had ridden for three years. “He was a very good teacher; with him I won my first Nations Cup” (at Gothenburg).

The most important partner of Rodrigo’s early years, though—and his favorite to the day—was Special Envoy. “My father knew exactly how I was riding, and he’d been riding the horse and knew how he would react to me.” Rodrigo and Special Envoy clicked from their first show together in 1990 (at Rome) and come third in the grand prix at Aachen a little later. They competed at that year’s World Championship (coming 23rd individually). Rodrigo was 17.

Special Envoy knew how to conserve energy. “He knew that working at home didn’t earn him any blankets or flowers, so it was horrible to jump him at home; he wouldn’t try at all. In the collecting ring at the show, he thought, ‘Oh, we’re at the show!’ and gave a little effort. Then in the ring, he was just special. He never overjumped a fence; he cleared everything by 2 centimeters” less than an inch. “He was consistent and smart—always thinking fast. He wanted to get into the ring; it was fun for him. He was just as competitive as I was.”

Rodrigo and Special Envoy never won a big championship. “But he won everything else, gave me some fantastic memories, built my confidence and put me on the map.”

Keeping the Pressure Off

Just ahead: the 1990s, the decade that would bring Rodrigo, in his 20s, the very same international titles that had eluded his father for a lifetime. Rodrigo ranks Nelson as the world’s best rider, ahead of his other top-rider picks (he unhesitatingly rattles off Germany’s Ludger Beerbaum, the US’s Michael Matz, Canada’s Ian Millar and Britain’s John Whitaker). And he sees the difference between father and son not as one’s ability (observers such as Katie Prudent see what she calls “the same light-in-the-saddle, forward-going” style in both Pessoas) but of temperament. “I believe,” Rodrigo says, “that if he was given the opportunities I was, eh would have won as well. But from the beginning of his career, my father has always been a nervous person, a stressed person. He’s ridden in many championships and missed because he puts a lot of pressure on himself.”

From an early age, the younger Pessoa saw that competition itself provides plenty of pressure. “You ride well, you train a lot, you have a good horse, everybody’s expecting from you. That’s already a lot of pressure. And if you say, ?Oh, everybody’s watching, I’m representing my country, I have to do this’?with that extra pressure on your back, you have no chance.” Instead, he says, he learned to contain the anxiety. “I have a little eknot in my stomach at the big moments, but I can contain it and let go afterward. When I’m riding, I don’t show it.”

“In terms of pressure, Rodrigo has been through things that most of us will never go through,” says Katie. “So how do you learn to handle it? By being there. At 27, he has the poise of a 40-year-old.”

Rodrigo was 19 when he rode for Brazil at the Barcelona Olympics, where he finished ninth individually. The youngest member of the team, he says he was also the calmest. “Partly it was because when you’re that young, you’re not really conscious of what’s going on,” he says candidly. But part of his calm was a conscious putting-aside of the pressure, a technique that would stand him in every better stead a few years later.

?The Best Horse in the World Today’

Riding in the World Show-Jumping Championship at the 1994 World Equestrian Games, Rodrigo finished eighth individually. Then he watched from the rail of the warm-up ring as the four finalists swapped horses for the suspenseful final rounds. “I thought, ?One day I wasn’t to be in there and give the other three a hard time.'”

Before the next WEG, though, came the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, where (once more a member of the Brazilian squad) he was two horses away from his turn in the ring with Tomboy when a thunderstorm halted the class. The cloudburst over, he coolly repeated the warm-up and jumped a clear round with 0.75 time faults, helping Brazil to team bronze: the country’s first-ever Olympic equestrian medal.

Less than two years later, Rodrigo began the series of stunning wins that eventually put him at the top of the FEI/BCM World Jumping Ranking. In 1998 he won his first World Cup Final, on Baloubet Du Rouet. That important victory was still fresh when he came to Rome for the 1998 WEG, riding a different horse (and recent addition to the Pessoa string), German-bred Gandini Lianos. When he found himself first individually in the team competition?and therefore one of the finalists for the individual Championship?after four days of jumping, he says, “I already thought it was something special.”

Rodrigo kept his composure?and his lead?through four more jumping rounds, one on Lianos and one each (after three-minute warm-ups) on the horses of co-finalistsThierry Pomel (France), Franke Sloothaak (Germany) and Willi Mellinger (Switzerland), to become World Champion. He had made his dream from 1994 a reality.

Next stop, 1999 World Cup Final in Gothenburg. But returning to the Final after winning it the previous year, and winning another major show-jumping title in between, didn’t feel like extra pressure to Rodrigo. He said afterward that his 1998 win had increased his confidence by proving to him that he could do it.

Rodrigo won the first round at the 1999 Final and just kept going. Part of his edge was his deepening partnership with Baloubet. “I think he’s the best horse in the world today, and it’s not just because I ride him. He’s extremely intelligent, very careful, very supple and he jumps these big courses as if it’s a game. I feel he’s thinking, ?Ha! Do they think they have me in trouble when they build these big fences?'” In a typical feat of spectacular athleticism, Baloubet saved a knockdown in the second leg of the 1999 Final by somehow touching down in the middle of a triple bar, then kicking off again, to compensate for a long takeoff spot.

?I’m Not Doing It to be Second’

But as Katie suggests, there’s an inevitable tradeoff for so much success so early. Start with the lifestyle imposed by world-class jumping. “My address is in Belgium; home is really in the airplanes and hotels,” Rodrigo says wryly. Spliced into his competitive schedule are frequent trips to Brazil, where he’s a national hero; he maintains contact with riders there who will spend summers training with Nelson in Belgium for future Brazilian teams. “You miss your house and you miss your family because you’re traveling so much.”

Another tradeoff is the deadening effect of victory after major victory. “Either you have the riding virus or you don’t,” Rodrigo says. “But before, it was automatic to be motivated for the opening class of every show. It’s different now; for normal competitions, I have to get motivated.” As a regular show approaches, he says, he consciously devotes about 10 minutes a day to thinking about it: “about the difficulties I could come to, and how to solve them.”

While the rest of the show-jumping world sees Rodrigo’s huge talent and the superb Pessoa horses as the cornerstone of his career, Rodrigo himself rates his “hard determination” to excel as his biggest riding strength. His explanation resonates with his father’s dedication to the sport and his own sense of striving to finish what Nelson began. “OK, my father did not win these titles?but through me, now he is winning as well. My determination is to try to win and be the best always. Because this is what I’m dong it for, not to be second.”

Then Rodrigo adds a strange little postscript. “If I’m doing it, I might as well do it very well?so I don’t have to do it twice.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2000 issue of Practical Horseman magazine. To read more about Rodrigo’s winning system, see “Rodrigo Pessoa: Don’t Settle for ‘Just OK'” in the October 2011 issue of Practical Horseman magazine.