Watching a horse cantering freely in a field, you’ll sometimes see him make flying lead changes so naturally and easily that they look like just another canter stride. During the moment in which the horse is suspended in the air, the leading front and hind legs smoothly change from one side to the other. (So, for example, say the horse is cantering on the right lead, with his right front and hind legs appearing to “lead.” During the moment of suspension, he changes the sequence of his footsteps so that the left front and hind legs now lead.) In a natural setting, the horse’s head stays level and his back and neck remain soft and relaxed. His hips and shoulders remain absolutely aligned throughout the process.

Flying changes under saddle should demonstrate all of these good qualities, as well. But when you’re first learning, it’s hard to know how much of this is your horse’s job and how much is yours. The ideal way to learn is on a horse who already does “automatic changes,” so you won’t both be new to the skill. Like an automatic car, an automatic lead changer seemingly “changes gears” on his own. But, just as with the car, he still needs a certain amount of input from his “driver.”

The key to making smooth lead changes is to give just enough input to your horse to cue the change without interfering with his relaxation, balance, straightness and rhythm. Unfortunately, some riders try too hard to produce changes, swinging their bodies dramatically in the saddle, pulling on the reins, throwing their horses off balance and making them tense and anxious. As a result, the horses lose their rhythm, change late behind (change the hind legs several strides after changing the front legs) and miss changes altogether.

My emphasis in this article on relaxation and smoothness is aimed primarily at hunter and equitation riders. But the skills I describe here also will benefit riders in other disciplines. By building on your own straightness, balance and clear understanding of the canter aids, you can set your horse up to make flawless flying changes every time.

Step 1: Perfect Your Canter Departure

Cueing for a flying change is much less mysterious than it seems. You simply ask for a canter lead while you’re cantering on the other lead. To perfect your aids for this, practice making canter departures, first from the trot (which is easier because your horse has more impulsion to carry into the transition), then from the walk, asking him to respond to soft aids the first time you ask. It is your responsibility to make sure he is sensitive, listening and responsive to your aids, yet still relaxed and happy. Here’s how:

1. Warm up sufficiently at the walk and trot, checking that your horse is responding well to your aids. Then pick a point along the arena fence to make the departure, marked by a cone, jump stand or something else visual outside of the ring, such as a tree. Trot along the fence line toward the point, staying 5 to 10 feet off the rail. Meanwhile, check that your horse is relaxed, soft in his back, neck and mouth and listening to your aids. (If he’s not, work to achieve that before practicing your canter departures.)

2. As you approach the marker, check that your shoulders are square and your body is centered in the saddle. Focus your eyes straight ahead while asking for a slight bend to the inside by closing your inside leg and bringing your inside rein slightly away from the neck and back toward your hip, encouraging your horse to curve his body around your inside leg. Meanwhile, maintain contact with your outside rein to keep him traveling straight on the line you’ve chosen.

3. In the next step or two, bring your outside leg back slightly, turn out your toe one or two inches and, keeping your leg long, squeeze your heel into your horse’s side. At the same time, close your hip angle slightly so that you stay with his motion while he lifts up into the canter.

If your horse doesn’t pick up the canter immediately, release the pressure of your aids and then ask for the departure again, making your outside leg aid stronger. Do not try to hold the initial aids until your horse canters. This will only make him crooked and off balance which, in turn, creates more tension and anxiety. Or if your horse is dull to the aids, it will make him completely nonresponsive.

If he doesn’t react to the stronger leg aids, release the aids and then reinforce your next ones using your stick behind your outside leg. When he does finally canter, reward him by softening your aids and allowing him to go forward in a steady rhythm. Repeat the departure several times until you’re confident that he’s responding promptly to your aids.

Each time your horse picks up the canter, remind yourself to stay straight and centered in the saddle. Many riders develop the bad habit of looking down to check the lead. This causes your shoulders to tilt, which throws your horse off balance as well. Instead, try to feel what your horse is doing underneath you without looking down. Ask a ground person to confirm the lead until you can do this reliably yourself.

Practice your canter departures in both directions, trying to time them so precisely that you pick up the canter at your chosen marker. When these are going well, repeat the same exercise from the walk.

Step 2: Simple Changes

When you’re making prompt, accurate canter departures in both directions and feeling balanced enough in the canter to use your hand and leg aids independently of each other, you’re ready to start simple changes. In these, you will begin on one canter lead, then make a transition to walk or trot for several steps before asking for the other canter lead.

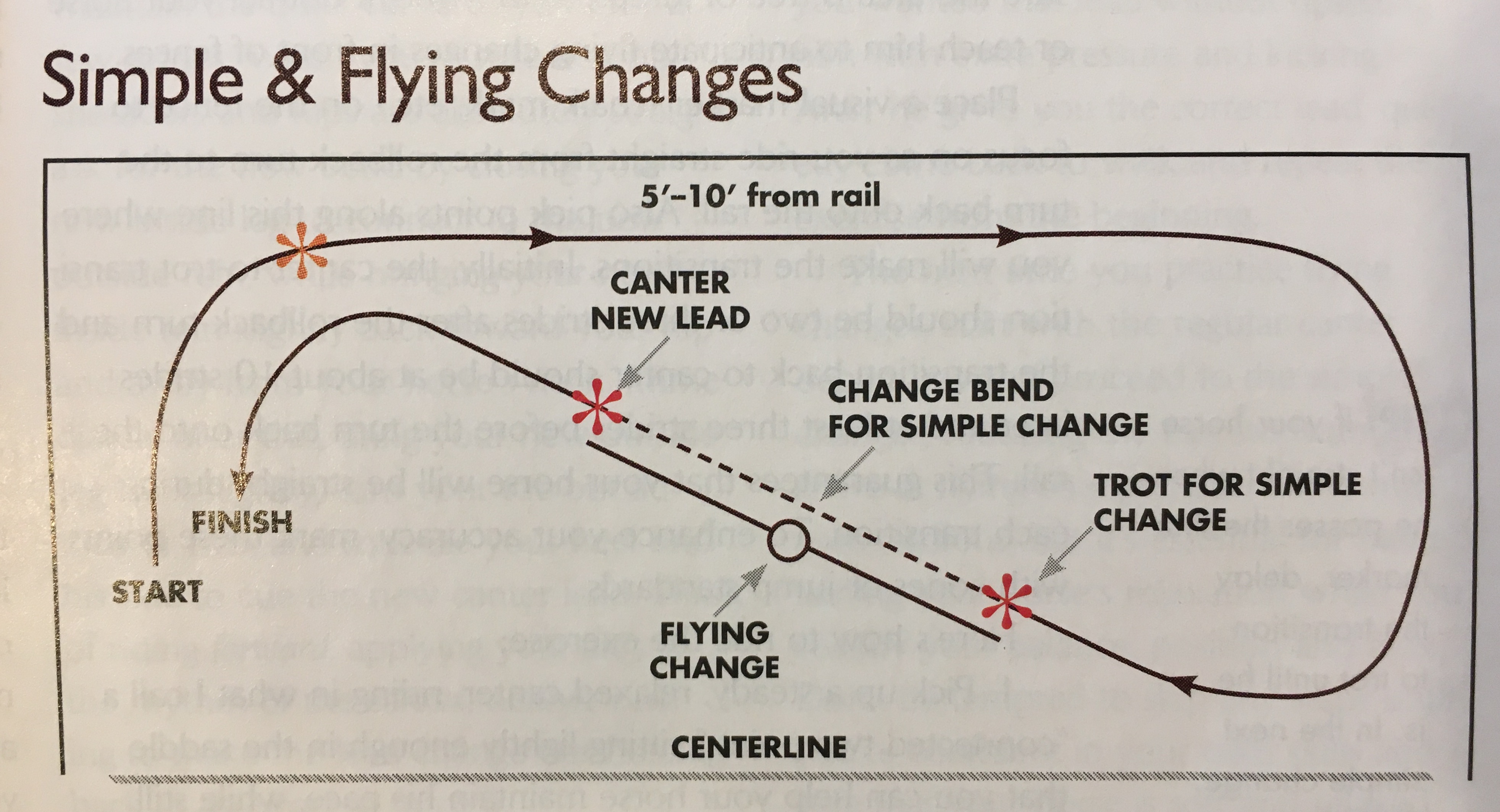

Begin by finding the best location in the arena to perform the teardrop shaped loop illustrated in the diagram above. You’ll need enough room to make a short, rollback turn off the rail and a straight, long ride back to it on a very shallow angle—so the turn back onto the rail isn’t too sharp. Be sure this area is free of jumps, as they might distract your horse or teach him to anticipate flying changes in front of fences.

Place a visual marker (chalk mark, etc.) on the fence to focus on as you ride straight from the rollback turn to the turn back onto the rail. Also pick points along this line where you will make the transitions. Initially, the canter-to-trot transition should be two or three strides before the turn back onto the rail. This guarantees that your horse will be straight during each transition. To enhance your accuracy, mark these points with cones or jump standards.

Here’s how to ride the exercise:

1. Pick up a steady, relaxed canter, riding in what I call a “connected two-point:” sitting lightly enough in the saddle that you can help your horse maintain his pace, while still allowing him to use his back. (I find that a deeper, “driving” seat makes many horses too strong and hard in the mouth, which ruins your chances of producing smooth flying changes). When your horse seems relaxed and listening to your aids, canter down the long side past your visual marker, staying 5 to 10 feet from the rail. Then make a short rollback turn, passing over or near the arena centerline, while closing your inside leg and bringing your inside hand slightly toward your hip to ask for the bend. To prevent your horse from falling in through his inside shoulder, think of “pushing” him with your inside leg toward your outside rein connection.

2. As you complete the rollback, soften your bending aids and focus your eyes on the visual marker. Square your own shoulders and hips and maintain your outside rein connection to gently straighten your horse’s body.

3. As you pass your first transition marker, use both reins to gently bring him back to trot, being careful not to use so much hand that he raises his head and becomes tense. As soon as he trots, soften your hands, still maintaining a light connection while allowing him to stay in a forward, soft rhythm. All the while, keep your eyes focused on the visual marker.

4. After several strides of trot, change the bend by applying your new inside leg to move your horse toward your new outside rein. Still focusing on the visual marker, bring your inside rein slightly away from his neck and back toward your hip, asking for a small bend to the inside. Use your outside rein and leg to keep his shoulders in line with his hips and maintain the straight line toward your visual marker. In the next step or two, bring your outside leg back a few inches and ask for the canter—while still focusing on the visual marker.

5. Continue straight for a few strides before turning back onto the rail, using your new inside leg to push your horse toward your outside rein.

6. Use your outside rein connection to straighten him again on the rail.

If your horse does not pick up the new canter—or if he picks up the wrong lead—bring him back to trot. Straighten him and ask for the new lead again, using slightly stronger aids to cue the canter departure. If he doesn’t canter before you reach the rail, go back to walk or trot and review your canter departures until your horse is responding promptly to your aids again.

The straight sections of this exercise are crucial as they ensure that your horse’s shoulders and hips are aligned for the transitions and they discourage you from pulling on your inside rein to turn. As you progress to the flying change, they’ll also prevent the very bad habit of pulling too much on the new inside rein to try to force the change—a habit that usually ends up unbalancing your horse and causing missed or late lead changes.

Step 3: Progressing to Flying Changes

When you’re comfortably executing simple changes in both directions, begin shortening the number of trot steps between the canters by making your transition to trot later and later. Do this gradually—over a period of many practice sessions—so that your horse continues to be relaxed throughout the exercise.

When you get down to a few trot steps—and your horse is staying relaxed—you’re ready to ask for the flying change. Plan your rollback turn just as carefully as you did for the simple change, choosing a spot for the change that is several strides past the initial turn and several strides before the turn back to the rail. This will ensure that your horse stays straight through the change and that you’re not tempted to pull him off balance with your inside rein. It also gives you enough room to ask again if he doesn’t respond the first time.

1. As with the simple change, be sure your horse is relaxed and responsive before entering the rollback in a forward, rhythmic canter. Lightly touch the saddle in your connected two-point position, using your inside aids again to bend him around the turn and push him into the outside rein.

2. After the turn, straighten him and maintain the quiet canter rhythm for a few strides. When you’re sure that his shoulders and hips are absolutely straight, ask for the new bend by closing your new inside leg to connect to the new outside rein, while bringing your new inside rein slightly back toward your hip and away from your horse’s neck. Immediately after this, bring your new outside leg back slightly, turn your toe out an inch or two, and squeeze your heel into his side to cue the new canter lead. Think of riding forward, applying your aids in the rhythm of the canter, neither rushing to make the lead change nor holding back in an effort to force it.

3. As your horse lifts up to change his leads, close your hips slightly to allow his back the freedom to arch up. Stay square in your shoulders and centered in the saddle, with your eyes focused on your visual marker. This will help him stay balanced and straight enough to make a clean change.

4. After the change, continue straight for several strides toward your visual marker. Then use a soft inside leg and outside rein to make a smooth turn back onto the rail.

Until you get the feeling of a flying change, it can be hard to identify when it happened and whether or not it was complete. A ground person can confirm that the changes are correct.

If you achieve a good flying change, softly come back to a walk, pat your horse (and yourself!) and repeat the exercise in the other direction. The fewer you do at this point, the better off your horse will be. Overdrilling flying changes can make horses nervous and tense—which lead to many problems.

If your horse doesn’t do a flying change immediately and you still have several strides left on the straight line before the rail, release the aids, check the new bend and ask for the change again with a stronger leg aid. If he still doesn’t do the change—or if you run out of room before the turn onto the rail—come back to the trot and ask for a simple change. This will make it clear to your horse that you wanted that lead without upsetting him with extra pressure and kicking. After he gives you the correct lead, quietly come back to walk and repeat the exercise from the beginning.

The next time you practice flying changes, start with the regular canter departures and proceed to the simple changes, reducing the trot steps until you arrive at flying changes again. This may seem tedious, but it’s essential for maintaining your horse’s relaxation while you solidify your balance, position and aids. Don’t be tempted to skip any steps until you’re confident in your own skills and sure that your horse is soft and relaxed.

When you are confident you can produce solid lead changes on the flat, then you are ready to do them after the jumps. Use the same techniques, including your visual markers to stay straight.

Remember: At any stage of this process, you may need to be clear and firm at times to keep your horse sensitive to your aids. But never be rough! Your horse can’t offer quiet, smooth flying changes until he’s completely relaxed and confident that he can trust you. With patience, though, you can help him produce successful, smooth flying changes.

Troubleshooting

Problem: You can’t produce the flying change.

Correction: If your horse has been a reliable automatic changer in the past, ask your veterinarian to rule out any physical discomfort that may be discouraging the effort. Also have your ground person watch carefully to see if you’re inhibiting him with an unconscious weight shift or too-strong reins.

If, after following all the steps above, your horse still won’t produce the flying changes in two or three attempts, leave the exercise and do something different until he settles mentally. Then go back to the earlier steps of perfecting your regular canter departures and simple changes. Building on these skills should eventually produce easy flying changes. Also, don’t advance to the flying change exercise late in a session when your horse’s fatigue may make it more challenging.

Problem: Flying changes are easier in one direction than the other.

Correction: Practice the flying changes in your good direction, paying close attention to everything you’re doing right with your position and aids. How much pressure do you have in each hand? Where is your weight balanced? Then try to transfer those good skills to the more difficult lead. Also work on your regular canter departures and simple changes in the difficult direction to strengthen his response to your aids. Again, if there’s no obvious cause of the problem, consult your veterinarian.

Problem: Your horse raises his head and quickens in the flying change.

Correction: This is the most difficult problem because it takes the most time and patience to correct. Never lose your cool when dealing with this problem, as it will only set you back further. Also, don’t try to correct him by going too slowly. This will only make your horse nervous because he knows he needs more impulsion to produce the change—and must create it on his own by getting quick.

Go back to simple changes until your horse relaxes again. Then try to use less hand in the preparation for the flying lead change. Establish a forward, relaxed rhythm and focus on following his mouth with your reins—while still keeping a soft feel of the contact to ask him to remain in the rhythm—and allowing his back to stay relaxed (no “driving” with your seat!) as he makes the change.

Problem: Your horse changes late behind.

Correction: This usually results from your horse anticipating the turn and dropping his shoulder, so his shoulders and hips are no longer aligned—or from your horse being too dull to your new outside leg. Be sure you’re not asking for the change too close to the rail (give yourself a marker for exactly where you’d like to make the change) and remember to focus on straightness. Keep your own hips and shoulders square, your body balanced in the middle of the saddle and your eyes focused ahead, always taking care not to make your inside bending rein aid so strong that your horse leans against it.

You can also set up a lane between two lines of cones, set about 8 feet apart, for the straight part of the teardrop exercise to help you visualize keeping your horse’s body straight.

If your horse is full to your outside leg aids, do some canter departures to remind him to be more responsive.

Problem: Your horse makes a lead change before you ask for it.

Correction: This tends to happen with horses who are drilled too much in flying changes. If you need to practice changes for your own sake, shorten the distance you ride along the long side before initiating your rollback. This will make the loop shorter, giving your horse less time to anticipate the change.

Sidebar: Different Changes for Different Disciplines

In the hunter and equitation rings, flying changes should be smooth and clean (no late changes behind). Dressage flying changes have more suspension and lift in the horse’s body. And in the jumpers, unlike the hunters and dressage, changes in a horse’s expression and other signs of tension aren’t penalized—but his quick response to your aids is paramount. Balance, straightness and relaxation are all essential, however, in all of these disciplines.

About Jennifer Bauersachs

Hunter trainer Jennifer Bauersachs has been the Leading Lady Rider at the Devon Horse Show on Mombo, Grand Champion at the Washington International Horse Show on Sterling and champion and grand champion at many other top indoor shows. Her students have won major championships in the Amateur-Owner and Junior divisions at shows such as the Pennsylvania National Horse Show, Washington International and Devon. Jennifer and her husband, Rolf, own Spring Hill Farm, in Frenchtown, New Jersey.

This article originally appeared in the June 2010 issue of Practical Horseman.