A reader asks: “My horse has a shorter-than-average stride and sometimes has trouble making the distances in big combinations. If I try to help him by going faster in the approach, he gets too flat and knocks rails down. He’s a wonderful jumper otherwise and I’d hate to give up on him. What can I do to help him with these big combinations?”

Top hunter/jumper trainer Scott Lenkart offers the answer:

This is a fairly common problem that is solvable in most cases. Horses tend to shorten their stride when they’re nervous—and they often get nervous when you ask them to speed up. So pushing your horse to go faster into big combinations is counterproductive. Instead, the key is to learn how to help him relax into his most comfortable pace. Once he’s relaxed, it’ll be easier to encourage him to stretch his stride out, bit by bit. This takes lots of practice at home.

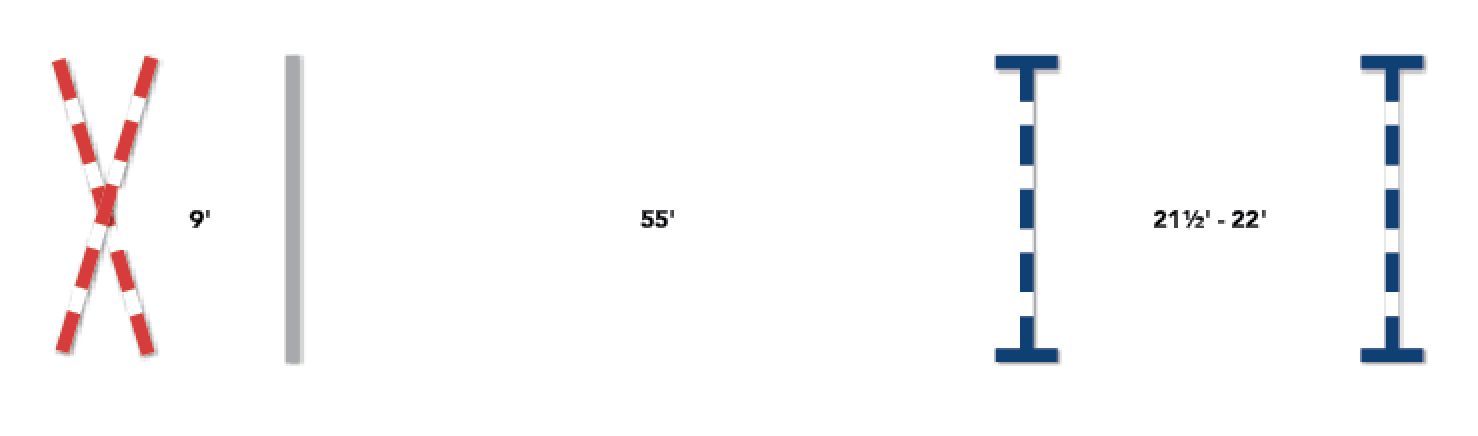

One exercise that you might find helpful is a simple grid consisting of a small crossrail, followed by a ground pole 9 feet away, then a one-stride in-and-out four strides from the crossrail (about 55 feet). Initially, set the in-and-out at a comfortable distance—about 21½ to 22 feet—to make it feel very doable for your horse. (For horses with a slightly bigger stride, I’d open that distance up somewhat, to perhaps 23 feet.) By trotting into this exercise, you’ll remove any concern about finding the right distance to the jumps. The ground pole will encourage your horse to land cantering after the crossrail, and the set distance will bring you to a nice takeoff spot for the “A” element of the combination. This is very important, as one bad distance to the “in” of an in-and-out can make any horse worry.

Build the in-and-out as either an oxer to a vertical or a vertical to an oxer, whichever is more comfortable for you and your horse. Make both jumps fairly small at first and ramp the oxer (build the front rail lower than the back rail). Add a ground line in front of each jump to make it more inviting.

As you trot into the grid, focus your eyes beyond the “B” element of the in-and-out. Stay in a light, forward seat, with your hands in front of your body. To avoid causing your horse to knock down a rail on takeoff, wait for him to leave the ground and then follow with your hand and upper body. When you land from “A,” rock back into your two-point position to make sure your leg is underneath you and your eyes are looking ahead, then ride to “B” in the same light, forward position. If the initial distances feel too long or short, adjust them accordingly to make them as comfortable as possible for your horse.

When this is riding well, widen the oxer a little bit. Always widen the oxer before raising it—and never do both at the same time. Then gradually increase the heights of the in-and-out fences. Keep the “out” jump smaller than the “in” jump, so it’s less intimidating. As your horse’s confidence grows, gradually lengthen the distance in the four-stride line to about 60 feet and the distance in the combination to 24 feet, always keeping the jumps very inviting, so he never feels threatened. So long as he stays relaxed, he’ll begin stretching his stride automatically. When that’s going well, lower the jumps again and try the opposite configuration (for example, oxer-to-vertical if you started with vertical-to-oxer).

To transfer these new skills to competitions, be sure to minimize any stress that might make you—and, thus, your horse—nervous. Allow plenty of time to tack up and get to the ring so you’re not rushed. Warm up with lots of flatwork to loosen up, relax and stretch your horse, spending more time in whichever gait he finds most relaxing. Use ground lines to help him arrive at good distances. Build his confidence by working your way up to a slightly wider (but not higher) oxer than you might see in the ring. Then finish with a somewhat smaller vertical or rampy oxer—whichever seems to suit your horse best—with a ground line.

On course, approach combinations in a normal canter. Stay in your forward seat and ride just the way you did at home. Remember to be patient on takeoff, then follow your horse’s motion with your hand and upper body. If he feels a little sticky, encourage him with a cluck.

Keep in mind, inconsistent riding can make your horse nervous. If he knocks a rail down—either at home or at a show—don’t overreact. Just continue practicing and doing your homework. As he begins to trust you and relax, he’ll learn to stretch his stride in the combinations as needed.

Scott Lenkart and his wife, Courtney, own and operate South Haven Farm, in Bartonville, Texas. Focusing on hunters, jumpers and equitation, they coach a limited number of riders, bringing them along from the beginner level to top placings in the hunter and grand prix arenas. Scott served as the USHJA Zone 7 team’s chef d’équipe at the North American Young Rider Show Jumping Team Championships in 2015. He and Courtney also train and compete a select group of horses through the highest levels of the sport—Courtney in hunters and Scott in jumpers. To date, Scott has won more than 45 grand prix events. They also buy horses in the U.S. and overseas to develop and sell to suitable riders.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2018 issue of Practical Horseman.