We lost Bill Steinkraus, America’s Greatest Horseman, recently, after a decades-long fight against cancer. The various obituaries about him are accurate but a bit dry, and I wanted to tell you a little more about him from my personal perspective.

He was a hero of mine. I hope that after you read this, he will be one of yours, too. I called him “Cap’nbilly” (all one word) and he called me “Little Brother.” Some explanation is required: In the South, “Cap’n” is a term of respect, rather than rank, and “Little Brother” did not refer to a familial connection, but rather to Bill’s conception of me as the little brother he never knew he had—or wanted.

In part, “Little Brother” acknowledged a relationship that was established early in our lives. My father was Bill’s first Olympic coach, and he rode my mother’s horse Hollandia in his first big competition—the 1952 Helsinki Olympics in Finland, where the team won a bronze medal. For the next 20 years Bill would serve as the show-jumping team captain, hence “Cap’nbilly.” Given the 20 years that separated us, I filled the role of a little brother—buzzing and whining on the periphery, always quick to interject and irritate, tolerated due to my somewhat unusual status. Yet at the same time, there was a fair amount of hero worship involved on my part.

A Superior Intellect

Bill’s intellect would have been one of the first things newcomers noticed about him. It could be irritating and off-putting at first because he carried himself with an instinctive assumption of superiority. But any extended exposure to Bill would lead you to the conclusion that he did not just have a superiority complex, he really was superior. Everything he discussed had already passed through the powerful lens of his considerable intellect. Thus, if you dared to disagree with him, you should (in another lovely Southern phrase) “pack a lunch and bring a lantern.” To disagree with Bill would take a while.

Looking back, I wish I had gotten in the habit of recording my conversations with him. The world would be a better place for the knowledge that poured out of him. At a moment’s notice, he could discourse on the difficulty of a violin sonata (at certain points in his life, Bill played violin at the symphonic level) and give an impromptu lecture on the similarities between preparing a serious musical passage and schooling a young show jumper. For the musical passage, you learned the mechanics needed to produce each musical note then played the movement in quarter-time, and then in half-time, and so on. Similarly, when training the show jumper, you could conceive of an educational progression that began at the walk over one rustic pole on the ground and finished at the Olympic Games. Along the way, the horse and rider would have practiced every possible combination of problems: vertical–oxer, oxer–vertical, oxer–oxer, vertical–vertical, and so on.

He was fascinated by the connection between horse and rider and studied its every aspect. He was a lifelong proponent of maintaining contact with the horse’s mouth throughout the jumping process. He wrote to me about this not long ago, saying, “I have always felt that ‘contact’ and even Bert’s [Bertalan de Némethy, long-time coach of the U.S. show jumping team] ‘connection’ are relatively clumsy, inexpressive words and prefer the French ‘l’appui bon,’ defined as ‘the reciprocal sentiment between the horse’s mouth and the rider’s hand.’ Good hands and l’appui bon come together.” This conviction made him an outspoken opponent of the crest release. To his mind, a rider could no more produce a trained jumper on a loose rein than a musician could produce a musical note with a slack string. He understood the educational process and occasionally advocated a loose rein when starting young horses, but loose reins on course were anathema to him. “Jimmy, they have turned a virtue into a defect,” was one of his many statements to me about the crest release.

Occasional Use of Profanity

Bill showed his equestrian talent early in his life, winning both the ASPCA Maclay National Championship and the Good Hands Finals (the saddle seat national championship) at Madison Square Garden in 1941. That same year, he entered Yale to begin his college education. However, World War II interrupted both his riding and educational careers. He joined the 124th Cavalry Regiment, did his initial military training at Fort Riley in north-central Kansas and served in the China–Burma–India Theater until 1945. The 124th Cavalry Regiment was made up mostly of Texas cowboys, oil-field roughnecks and other rambunctious types. By all reports, this produced a group of hard-riding, hard-drinking, rowdy young men. Naturally when war broke out, the Army, in its infinite wisdom, filled out the ranks of the 124th with polo-playing students from Ivy League colleges, which produced a culture clash of spectacular dimensions. But each group learned from the other and by the time they shipped out, they were truly a unit

Like most combat survivors, Bill rarely spoke of his experiences in the war. He did mention on one occasion that the only positive thing he learned from war was that, despite grinding fatigue and horrible conditions, he could always “put one foot in front of the other.” As I spent more time with him, I noticed another surprising trait—his occasional use of profanity.

The 124th originally trained to ride into combat on horseback and to move their supplies with mules. Once in their assigned operations area, they quickly realized that horses were not suitable for combat in the jungle. Mules, on the other hand, were very useful, and so Bill spent much of his wartime as a mule skinner. Another of my heroes, Gen. Ulysses Grant, who served in the Mexican–American War 1846–48, never used profanity or obscenity. He once remarked that, “I am not aware of ever using a profane expletive in my life; but I would have the charity to excuse those who may have done so, if they were in charge of a train of Mexican pack mules at the time.” Bill almost certainly did not use Mexican pack mules during WWII, but I am sure he would have appreciated Grant’s sentiments. I have often thought that Bill’s unusual command of the English language was embellished by his very occasional profane, obscene and amusing comments. These expressions never occurred in “polite company” and certainly never in mixed company, but they were invariably funny and suited the moment.

Bill and Democrat

Bill returned to Yale after the war, graduating in 1949. He studied the writings of Gen. Harry D. Chamberlin during this time and told me that Chamberlin had a major influence on his own riding and teaching.

Returning home from his first Olympics in 1952, Bill was a member of the U.S. Nations Cup team at the National Horse Show, then held every November at Madison Square Garden. “The Garden” was our biggest horse show during the early 1950s and certainly the most formal. In my mind’s eye, I still see Bill, slim and composed in his pink U.S. Equestrian Team coat and white britches, wearing his team uniform with the same style as Fred Astaire wearing white tie and tails. Horse shows in that era were not covered in the sports pages but rather featured prominently in the society pages. During the evening sessions, ladies in the audience turned out in long dresses and diamonds while the gentlemen wore black tie during the week and white tie and tails over the weekend. (As a child, I was mystified by the slight odor of mothballs that attended the proceedings. Later on I realized that the Garden was a huge occasion in the horse world and people’s formal attire was packed away from year to year.)

Bill’s ride at the Garden that year was Democrat, who was quite a horse. He was Col. F. (Fuddy) Wing’s ride in the 1948 London Olympic Games and competed on the 1952 Helsinki Olympic team with Capt. John Russell. At the Garden that year, Bill quickly established himself when he and Democrat jumped the whole week without a knockdown and won every individual class they entered. In addition, they won every individual class at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, (then an international show) and the Royal Winter Fair in Toronto, Canada. It is no wonder Bill later remarked, “Democrat was probably the most generous horse I have ever ridden.”

Olympic Individual Gold: ‘Git ‘Er Done’

During his riding career, Bill maintained an even temperament, never seeming in a hurry, never flustered, always cool and composed. Bertalan de Némethy once remarked to me that he had to “jump up and down and wave the American flag at him” to get Bill to call on his horse for extraordinary exertions to support a team effort. My supposition is that Bill could tell when his horse was having a good day and reacted accordingly. His long-time traveling groom, Dennis Haley, loved Snowbound, Bill’s 1968 gold-medal-winning mount, almost as much as he loved Bill. Dennis told me that during the USET show-jumping team’s European tours, he would stand at the in-gate after Bill warmed up for a jump-off. It didn’t always happen, but if Bill looked at him and winked, Dennis would immediately turn to a groom from a foreign team and bet on “Cap’n Billy.” Dennis told me he paid his considerable bar bill with his winnings.

Bill’s feel for his horse partly explains the extraordinary effort he and Snowbound produced to win their gold medal in Mexico City. In his early 40s by then, Bill must have realized that Snowbound was having a good day and it was now or never for his individual career. You will see what I mean by watching Bill’s video clip on EquestrianCoach.com’s YouTube channel: www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2VpsxNy-Io.

Bill was famous for his style and the effortless, flowing way that his horses went around the course. But on that day, over the biggest show-jumping course that will ever be built (the rules have since been changed), Bill ignored smooth and flowing for as dramatic a display of “git ‘er done” as I have ever watched. Dennis probably paid off his mortgage with his winnings that day.

Excelling at Everything

Bill’s riding accomplishments would be enough to put him into the Show Jumping Hall of Fame, but he excelled in everything he attempted. It was a rare aspect of the horse world that did not feel his deft touch. Following his retirement from international competition, he was elected president of the USET, where he led what at that time was one of the most successful equestrian organizations in the world. Bill served two terms on the FEI Show Jumping Committee, was a member of the FEI Bureau (basically the executive committee of the FEI) and was the driving force behind the development of the Show Jumping World Cup. During that period, I was fortunate enough to serve with Bill on several ad hoc FEI committees and was always impressed with the clarity of his thought and the articulate way he expressed himself.

One of the many ways he improved the horse world was in leading the reorganization of the FEI leadership structure. An important part of that effort was in the imposition of term limits on members and officers. When I first started attending FEI meetings in 1981, I was startled to meet a representative from one of the communist bloc countries who had been a general in their army—in World War I! At that time, representatives viewed their participation as lifelong appointments regardless of any diminution in their mental and physical capacities. I later told Bill that I was impressed he was able to get that particular change voted on and approved, as it was the first time I had ever seen turkeys vote for Thanksgiving.

Any study of Bill’s life would be incomplete if it did not mention his writing ability. A major part of his success during that period of much-needed change at the FEI was his ability to write clear and convincing papers in defense of our proposals. His two books on riding, Riding and Jumping, published in 1961, and Reflections on Riding and Jumping (1991), are both marvelous and deserve the place of honor in any horseman’s library.

It is hard to explain Bill’s influence to the modern world. His long fight with cancer robbed us of his best years, but he made the world in which you and I live a better place. It is typical that Bill, who always had the last word, wrote his own obituary. It is grammatically and syntactically correct and describes his career succinctly and completely. But it fails to show us more than a dry description of him and leaves us with no understanding of the role he played in the horse world or his deep, abiding love for horses. One gets a hint of his inner feelings, however, in the closing paragraph of his last book, where he says, “No throne can compare with the back of a horse, and there is no way in which man can come closer to nature than by becoming one with a horse.”

I watched many warm-up arenas during my time, and when good riders warmed up, their supporters and staff paid close attention. But when Bill warmed up, other riders paused and the entire arena watched closely. We all knew we were watching something different and something better. Cap’nbilly was a close friend of mine and a friend of all who loved horses. With his passing, the horse world has lost one of its greatest horsemen. But we have his example and his writings to guide us, and all we can do, in his memorable phrase, is to keep putting one foot in front of the other.

Bill, Bold Minstrel and the Bank

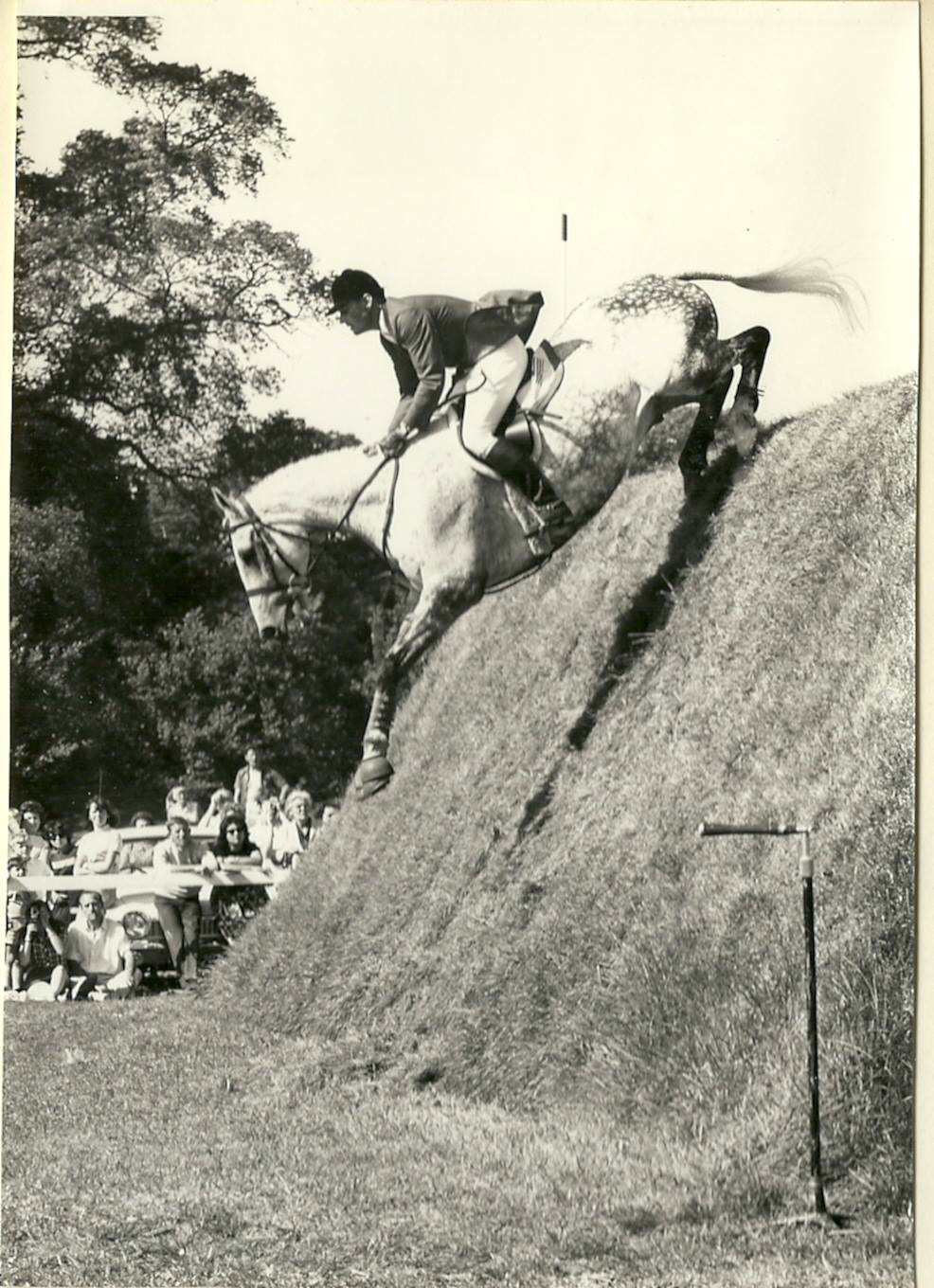

I love this photo of Bill Steinkraus and Bold Minstrel, taken in 1967 at the All England Jumping Course, Hickstead, England. It’s not often you see one of the world’s greatest riders and one of the best horses in the world together in competition. Bill would soon be an Olympic gold medalist and Bold Minstrel had already won a silver medal on the 1964 Olympic eventing team. This was an unusual combination of talents. Bill was one of the most accurate riders I have ever seen. In the spring of 1967, I watched him schooling Bold Minstrel at the USET training center in Gladstone, N.J. Imagine a 5-foot brick wall set on the center line of the main outdoor arena, and close to the out-gate. Bill turned onto the centerline from the other end of the arena, approached the wall, made a slight half-halt 125 feet away and cantered quietly to a perfect takeoff. He landed on the right lead, circled back and jumped it on a 45-degree angle landing on the left lead, circled back left-handed and jumped it again for the third time. When I walked over to the wall, all three takeoff footprints prints were in the same spot and you could cover those footprints with a dinner plate.

Considering his accuracy, it is startling to see Bill and Bold Minstrel jumping all the way down the infamous Hickstead Bank. Bill later admitted that he was surprised by this unscheduled departure into space. He may have been surprised, but he maintained his usual flawless technique. This was the first time Bold Minstrel had seen the Bank, and—being a former eventer—he decided to jump the whole thing. The bank is listed at 10’ 6” so it is understandable that Bold Minstrel went to his knees upon landing.

This article was originally published in the March 2018 issue of Practical Horseman.