I was born in a different century. What with computers, cell phones, jet airplanes and all, I am continually reminded of this. I have been connected with horses all my life and have lived through some changes with the sport. For this month’s column, I thought I would take a look back, and tell you about some of the things I have seen along the way. I feel that I have an unusual vantage point, because I literally grew up with the US Equestrian Team.

Jim Wofford’s father, Capt. John Wofford, competed on the US show-jumping team at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Jim Wofford’s father, Capt. John Wofford, competed on the US show-jumping team at the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.I was born and raised on Rimrock Farm, a horse farm in Kansas. It backed up to Fort Riley, which was the home of the US Cavalry between 1920 and 1945. This meant that I had thousands of acres of short-grass prairie to ride over, and I had some hair-raising experiences out there with my four-legged friend, Tiny Blair. I can remember riding out onto the military reservation early in the morning, dressed in blue jeans, ragged T-shirt, high-topped tennis shoes and no helmet, carrying a fishing pole, with a rifle tied to one side of the saddle and a gunnysack full of PBJ sandwiches and Dr. Pepper tied to the other. Basically a one-man (boy) crime wave on horseback.

My family had an unusual connection with the Olympics, so I have always remembered things based on the Olympic quadrennial. My father rode on the 1932 Olympic show-jumping team in Los Angeles and was reserve on the team in 1936. The first Olympics I remember were in London in 1948. The US Army was still in charge of all three Olympic equestrian disciplines, so the riders were all officers, the horses were for the most part owned by the Army, and the grooms and farriers were all enlisted men. Master Sgt. Harry Cruzan was Maj. F.F. Wing’s groom then, and I remember him telling me that they had a heavy wooden trunk for each horse, an additional one for the vet, one for the farrier … and one full of whiskey! I think whiskey played a larger part in those people’s lives than it does now, which is progress.

It is worth noting that it was common in that era for young officers to ride in more than one discipline. Gen. Guy V. Henry, later Chief of Staff, US Cavalry, rode in both dressage and show-jumping in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. In 1932, Gen. Harry D. Chamberlin won the individual silver medal in show-jumping and was on the gold-medal eventing team. In 1948, Gen. Frank S. Henry won the team gold and individual silver medals in eventing and a team silver in dressage, becoming only the second US rider to ever medal in two Olympic disciplines. If you asked me what is the biggest change I have observed since then, that would be my answer … that riders these days are specialists.

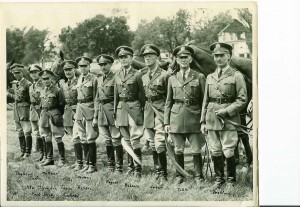

The 1936 US Olympic team included (from left): Capt. Earl “Tommy” Thomson, Lt. R.W. Curtis, Capt. M.H. Matteson, Col. Issac Leonard Kitts, Capt. John Willems, Capt. Carl Raguse, Capt. Stanley Babcock, Capt. C.C. Jadwin, Col. Hiram Tuttle, Capt. W.B. Bradford.

The 1936 US Olympic team included (from left): Capt. Earl “Tommy” Thomson, Lt. R.W. Curtis, Capt. M.H. Matteson, Col. Issac Leonard Kitts, Capt. John Willems, Capt. Carl Raguse, Capt. Stanley Babcock, Capt. C.C. Jadwin, Col. Hiram Tuttle, Capt. W.B. Bradford.Years later, I commented to my mother that team selection was getting more and more competitive. “You have no idea” she told me. During Prohibition, the Army Horse Show team would go up to the Royal Winter Fair in Toronto. The horses would ship up on special trains, and the team would always take a certain horse who wasn’t much “‘count” when it came to jumping, but he was hell to kick, and no customs officer in his right mind would get in the stall with him. On the way up to Toronto, they would store their hay behind Widowmaker, and on the way back down they would build a wall of hay that concealed a year’s supply of whiskey for all concerned. “You just think teams are competitive these days,” my mother said. “Those young officers would have killed each other for a chance at a year’s supply of whiskey!”

I was only 3 years old during the 1948 London Olympics, so I remember very little of that time. I do recall that the damage done by the Blitz was still evident everywhere, and rationing was still in effect, so my mother had brought an extra steamer trunk full of Hershey’s chocolate bars, silk stockings, and other delicacies and necessities. She also brought a case of rice, which had been unavailable since 1939. Fortunately, I found a way to jigger the lock on the trunk and break into the chocolate stash, so I stayed sugar-buzzed for the entire trip. While Gen. Humberto Mariles was winning the gold medal in show-jumping on Arete, I snuck into the enclosure at the base of the Olympic flame tower in Wembley Stadium to do what little boys do. A horrified English bobbie, helmet and all, chased me over the fence, calling me a “horrid little boy.” He did not know how right he was.

By the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, the Olympic equestrian team was a civilian operation. The US Army had mechanized in 1949, which meant the cavalry was disbanded. In 1951 the USET was formed “to train and field teams for international equestrian competition.” My father was the first president of the USET, as well as coach of the eventing and show-jumping teams. He must have been a busy man. The team training center in those days was at my parents’ Rimrock Farm. In the summer of 1952, we loaded a special train in Junction City, Kansas, and I remember riding the train to a siding at Fort Riley, where the horses and equipment were loaded. The three teams left for a European tour leading up to the Helsinki Olympics. (One thing about training teams that has not changed is the continuing need for European exposure before big competitions.) The horses crossed the Atlantic on a British cargo ship, the Parthia, and once they got to Europe they traveled by rail, as horse vans were not yet in general usage.

1948 was the last time the US Army fielded an Olympic equestrian team. It included (bottom row from left)–Lt. Col. Charles Symroski, Capt. Jonathan Burton, Col. Charles Andreson, Capt. John Russel, Lt. Robert Borg. Top row (from left)–Lt. Col. Frank Henry, Col. Franklin Wing, Jr., Brig. Gen. John T. Cole (manager), Maj. General Guy V. Henry (chef d’equipe), Col. Earl “Tommy” Thompson, Col. Andrew Frierson, Lt. Col. Harvey Ellis (vet).

1948 was the last time the US Army fielded an Olympic equestrian team. It included (bottom row from left)–Lt. Col. Charles Symroski, Capt. Jonathan Burton, Col. Charles Andreson, Capt. John Russel, Lt. Robert Borg. Top row (from left)–Lt. Col. Frank Henry, Col. Franklin Wing, Jr., Brig. Gen. John T. Cole (manager), Maj. General Guy V. Henry (chef d’equipe), Col. Earl “Tommy” Thompson, Col. Andrew Frierson, Lt. Col. Harvey Ellis (vet).Helsinki was a lovely venue for the equestrian part of the 1952 Games, but given my age at the time, I was far more interested in watching the sinister-appearing KGB agents hustle the USSR riders out of a van and into locked stables than I was in the fact that the USET won bronze medals in both eventing and show-jumping. This was the first instance I can recall of the trend towards the politicization of the Games, but the Games have never been as pure as Baron de Coubertin would have wanted us to believe. I wasn’t around yet, but my parents were in the stands in 1936 at the Berlin Olympics when Hitler refused to award Jesse Owens his gold medal. This trend has continued in various forms with the Communist riots and Black Power protest in 1968 in Mexico City, the Black September terrorists’ murder of the Israeli athletes in Munich in 1972, and the US and USSR boycotts of 1980 and 1984. You can be sure that human-rights advocates and environmentalists will be making things lively in Beijing this summer. As a personal aside, my oldest brother, Jeb Wofford, was on the bronze medal eventing team at Helsinki. The average age of the riders on the eventing team that year was 20, and the average age of the horses was 7–quite a contrast with riders and horses of today.

The Team horses traveled by air for the first time in 1956. This was considered cutting edge, because before that time travel to Europe entailed a lengthy sea voyage for the horses. (Sea travel continued to be the only option for some horses. In 1972 Sloopy, Neal Shapiro’s ride on the show-jumping team, had to travel by sea. He had been left behind from the 1971 tour because he had a fit before the plane took off. The extra trouble was worth it, as Neal and Sloopy won an individual bronze medal in Munich. The USET was understandably reluctant to ship a horse by air that had a history of traveling badly?Markham, Mike Plumb’s ride for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics in eventing, had thrown a high-altitude fit between JFK and O’Hare, and had to be destroyed en route.)

The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia, but the equestrian disciplines took place in Stockholm, Sweden, due to the equine quarantine regulations in force in Australia at that time. Stockholm had been the site of the 1912 Olympics as well as the first time that equestrian disciplines had appeared on the Olympic schedule of competitions, so the basic facilities were in place. Fortunately, by 1956 I was housebroken, so the police did not have to chase me away from the base of the tower containing the Olympic torch. My middle brother, Warren Wofford, was the reserve rider for the US show-jumping team, and I was too busy fighting with him to get into too much trouble otherwise. The 1956 equestrian Olympics used the same stadium that had been constructed for the 1912 Games. This is a very warm, intimate brick structure, and when the stadium was once again used for the 1990 World Games, I went to the same seats we had in 1956 and sat there for a moment and thought about all the wonderful horses and riders I had watched in that stadium.

The US eventing team of (from right) John “Jeb” Wofford, Charles “Champ” Hough and Walter Stanley Jr. (obscured) won the bronze medal at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Gold went to the Swedish team (center) and silver to Germany (left).

The US eventing team of (from right) John “Jeb” Wofford, Charles “Champ” Hough and Walter Stanley Jr. (obscured) won the bronze medal at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Gold went to the Swedish team (center) and silver to Germany (left).I have seen horse sports change over the past 60 years, and not always for the better. Yet I feel sorry for people who have not been involved with horses as I have been, because I have been truly blessed. Yes, changes have occurred, but the people involved retain their love of horses, and the horses remain the same wonderful creatures they have always been. They inspire us, and they make us better, just for our being around them.

This article was originally published in the February 2008 issue of Practical Horseman.