Kent Farrington stood before a crowd of auditors in dark sunglasses and a hat, exuding confidence and giving off an air of star quality. He answered questions calmly and completely as one hand after another shot up to ask about everything from training methods to competition schedules to building confidence in his mounts.

The impromptu Q & A session was part of a multiday clinic designed to identify and develop the next generation of U.S. Equestrian Team talent. The 2020 Olympic silver medalist, who as a kid began riding at a Chicago carriage stable, talked of the endless hours of hard work and shared another of his secrets to success—studying other riders. He explained that when he got the rare opportunity to go to bigger competitions he would stand by the warm-up ring and watch.

“I would know what equipment they were using. What bridle they had on. What kind of warm-up they were doing,” he rattled off. “Were they wearing spurs? Did they carry a stick? How short were their stirrups? Did they finish with an oxer or a vertical? How many fences would they jump? I would notice everything. So by doing that, I was gaining a lot of knowledge and free lessons, as I call it.”

Kent’s belief in the importance of attention to detail and the power of observation was evident throughout his gymnastics masterclass as he asked the 12 participants to study not only their own horses and think about what would make them better individually, but also to take advantage of free lessons by watching other riders work through problems with their horses.

The Warm-Up

Kent encouraged riders to take their time in the warm-up and likened it to human fitness, emphasizing the importance of letting the horse stretch to become loose while feeling for any soundness issues before asking the horse for more.

“I ride a lot off of feeling,” Kent stated. “It’s important for me to feel what is right for the horse and not a matter of robotic routine. Go with what feels right for that particular horse on that particular day. If he’s a little stiff or a little slow, I might spend more time at the trot. If he feels good, then I might move on more quickly to the canter.

“One thing I notice when I see people riding at shows, even at a high level, is how fast they ask a horse for a demanding compression of stride even at the trot,” he said.

While riders worked to get their horses to stretch, Kent instructed them to come off the rail about 5 to 10 feet to encourage straightness and to practice centered riding to help the horses have better balance. Participants also were instructed to reverse direction by rolling back into the wall, which helps make horses more obedient because they don’t anticipate turning in that direction. “You’re building habits every day, a little bit better or a little bit worse,” he said.

He asked several riders to relax in their positions and be a bit more natural to help the horses to relax and work better. He explained that while everyone has a different body type and different way of riding, all that matters is that the core principles are the same: Riders are in the middle of the horse and the horse is responsive to the aids.

As the riders worked in the trot, Kent asked them to change seats from rising to sitting trot. In the sitting trot he wanted them to go very slow—almost a jog—so that it was comfortable and the horse was accepting the seat and waiting.

“Whenever I’m uncomfortable sitting at the trot, I just go slower,” Kent said to Alex Pielet, who was struggling with a quick horse.

Kent encouraged Olivia Woodson, also on a hot horse, to work on teaching her mare to have a longer but not faster step. Kent asked the rider to do walk–trot transitions until she could find a balance between the two speeds. Then he had her switch back and forth from a posting trot to a very slow sitting trot—almost a walk. “This is a good way to work hot horses and get them to calm down,” he said about the simple transitions.

As in the trot work, when Kent asked riders to shorten and lengthen their horses’ strides, he had the riders canter at a normal pace and then get into a lighter seat while asking the horses for a longer stride. He reminded Sara McCloskey to stay centered—almost vertical—in canter. “Make sure when you go from sitting to a lighter seat that you’re not pitched ahead of the horse,” he said, explaining that although it’s a tiny difference, thinking about it on the flat will help with jumping.

“It’s going to make you slower with your upper body,” he elaborated. “When I go to a lighter seat, it’s almost like I’m going straight up, like something is pulling at the top of my head, not that I’m pitching forward over the horse’s ears.”

Similarly, he explained to Cecily Hayes that on her big, slow-moving horse she had to be cognizant that she didn’t get ahead of the front of the saddle when lightening her seat. “On that style of jumper you have to be very aware of your position in order to help him jump clear.”

Riders also worked in counter-canter in both directions to help improve each horse’s balance. If a horse was weak, Kent allowed the rider to use the wall to help find the balance and then come off the wall again.

When Kent asked riders to change directions in canter, he again stressed the common theme of training the individual horse. “It’s not any better doing a flying change,” he said. “This is more about training the horse. On a colder horse who is slow to my leg I would make him do a flying change. On a hotter horse that I’m trying to slow down, I don’t think I would ever do a flying change on the flat.”

Gymnastic Work

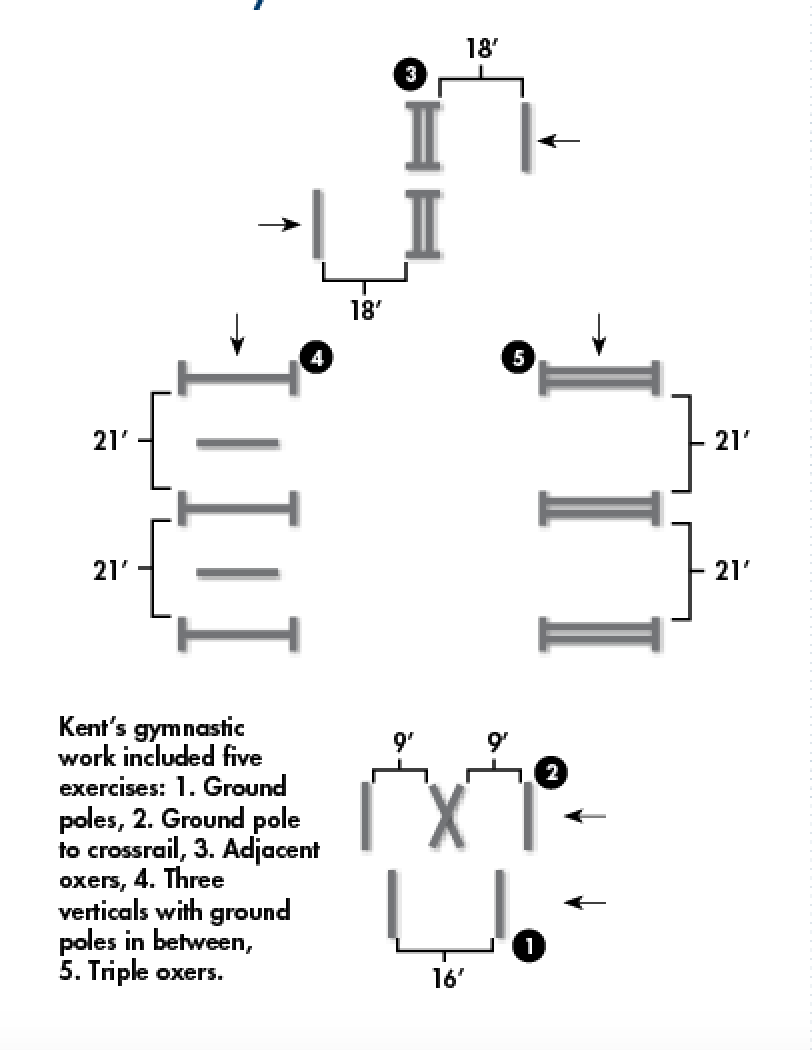

After horses and riders were warmed up, they worked on different gymnastic exercises, adding a new exercise each round until they were jumping a varied gymnastics course. Kent noted that the distances he used in the grid work were what he called “generic” distances, or something he would start every horse with and then would adjust depending on what was being worked on. For example, if his horse was struggling to cover the distance, Kent might make the distance slightly longer so the horse had to stretch—so long as it was within the horse’s capability. On the other hand, if his horse was eating up the distance, Kent might make it a bit shorter so the horse would get accustomed to a short distance and learn to wait.

At home, Kent typically does gymnastic work once a week and course work once a week and is careful to be very deliberate with the amount of jumping. “I don’t want to jump extra jumps for fun,” he said. “You’re just beating up on the horse for no reason. The least amount of jumping I can do to accomplish the lesson—that’s my goal. … I can teach him to slow down on the flat or over poles and then build the jump up to as small as possible to get where I am trying to go.”

As he did on the flat, Kent asked riders to focus on feel and gave them options in certain parts of the exercises to turn, circle or stop when they felt they needed it to better the horse.

Exercise 1: Ground Poles

Setup: Two ground poles 16 feet (one stride) apart

Kent instructed the riders to approach the simple ground-pole exercise on a normal canter without controlling the stride too much and to catch it once off the right lead and once off the left. Horses were to quietly canter over the first pole, take one stride and land on the other side of the second pole. The distance was set at 16 feet as a specific training exercise to make riders practice patience, and wait for a “disciplined” distance. “You don’t want a flying distance over the rail, where it’s super long,” he called. “Just step over.” He admitted that the distance might feel a little long to riders aboard horses with shorter strides.

Lessons from the flatwork were quickly carried over as Kent reminded riders to keep their upper bodies from jumping forward at the poles.

Exercise 2: Ground Pole to Crossrail

Setup: Ground pole 9 feet to a crossrail, then 9 feet to another ground pole

This exercise was used as a control exercise in which a quieter and shorter distance worked better than a long one. Horses were to canter the pole, take a quiet bounce step over the crossrail and finally, a bounce stride over the second pole. Kent noted that if the fence had been much larger, it would be set at a longer distance. First, riders went through Exercise 1 on the right lead, quietly stopped or did a downward transition, then turned left into the arena wall before approaching Exercise 2 on the left lead.

“This is an easy distance to the pole coming in. That’s why we wanted to practice the disciplined distance at the poles,” said Kent. “Don’t just fly at the rail. If you’re not sure, always add one stride.”

Since Exercise 1 was set at the end of the ring, the horses anticipated going right after the exercise because there wasn’t as much room to turn left. Kent stressed the importance of training the horses to turn left and roll back into the wall, reprogramming them to stay in tune and to hold the line where the riders wanted to go.

“The idea of turning backwards into the wall is that the horse doesn’t anticipate the turn,” Kent said. “It’s going to teach them better balance and to slow down and wait for the rider to know where they’re going next so that they’re not anticipating and taking it into their own hands.”

Echoes from the flatwork came through as Delaney Flynn struggled with her horse’s pogo-stick canter. Kent told her to encourage the horse to have a long stride without being fast. He had her circle first to get a longer stride before approaching Exercise 2. “Don’t let him canter in place,“ he called. “Accelerate around the end and [be] patient at the exercise.”

Exercise 3: Adjacent Oxers

Setup: Two oxers set side by side at the end of the ring with a ground pole 18 feet (one stride) in front of each oxer

After riders went through Exercises 1 and 2, they cantered down the long side on the right lead to the other end of the arena where Exercise 3 was set. They cantered over the ground pole closest to the center of the ring, took one quiet stride, jumped the oxer, then made a left circle before they approached the ground pole and oxer closest to the rail in the same fashion. Riders then executed a rollback turn to the right, again as in Exercises 1 and 2, heading in the opposite direction the horse would anticipate.

“You can make a circle in between, you can turn right after the first one, you can halt after the first one,” Kent said. “It doesn’t matter to me. I want you to think about the horse that you are riding, how you are setting him up for the course you’re going to do tomorrow and what’s going to be productive training.”

When Olivia jumped Exercise 1 and halted, Kent told her that on her hot horse she should have transitioned down to walk or, even better, a very slow trot to keep the mare’s mind quiet.

“There’s no rush, there’s no time limit here, just train the horse,” Kent said deliberately as he asked Olivia to make a circle before approaching Exercise 2. “It’s really important to me when I’m schooling a horse that I’m not on a clock for anything. You’re thinking about how to make this horse better for your course tomorrow,” he continued, referring to the mock Nations Cup scheduled for the following day. “She has to be obedient, slow, on a longer stride than she naturally wants to carry while, at the same time, being relaxed.”

After Exercise 2, Olivia trotted down the long side and made a circle at the canter before approaching the oxer. “Perfect,” praised Kent. “I like that. There’s no limit to what you can do. You make it work for your horse. If you need to make a circle or make two circles, it’s no big deal.”

In contrast, Kent reminded Caitlyn Connors, whose horse was “a bit slow off the spur, hanging off the back pole [of the crossrail in Exercise 2] and almost landing on the ground line” to be ready with a cluck so that he moves. “Make sure you’re covering the distance by using your leg or your cluck, not by getting there with your shoulder,” he warned.

When the horse hung on the bridle and tried to go right after the crossrail in anticipation of heading to Exercise 3, Kent had Caitlyn turn him left and make a half circle. “He wants to go to the right, don’t let him,” he said, reinforcing his earlier lesson about reprogramming the horse to go in the line the rider wants.

As Caitlyn headed down the long side to Exercise 3, Kent again told her to use leg and a cluck so that her horse wouldn’t be “asleep on the back rail of the oxer.” When the horse made a lazy and slow effort over the second oxer, Kent had her jump it again, instructing her to accelerate through the turn to teach the horse to move off the leg and to carry her better.

.jpg)

Exercise 4: Three Verticals with Ground Poles In Between

Set up: Three verticals in a line, 21 feet (one stride) apart, with a ground pole exactly in the middle of each jump

This time Kent told riders to skip Exercise 1 and instead start with Exercise 2 off either lead, jump the oxer closest to the center of the ring in Exercise 3 then turn left, canter around the outside of Exercise 3 to Exercise 4, three verticals with ground poles in the middle of each one. Riders jumped the first vertical, took a bounce step over the first ground pole to the second vertical and then took another bounce step over the second ground pole to the third vertical. Finally, riders turned right and cantered down the long side again, rolling back to the oxer closest to the rail from Exercise 3.

A lot of Kent’s comments focused on the rider’s position through the verticals. He repeatedly told riders to keep their positions quiet and centered through the line and explained that while a lighter seat was necessary for asking for a longer stride, riders had to be careful not to pitch their upper body forward.

“Make sure when coming through verticals you aren’t jumping with your body,” he called to Kendra Duggleby, who leaned slightly at the fences with her shoulders. “Let the horse do the work at the fence.”

But the biggest challenge that seemed to face riders in this exercise was not the addition of the three verticals with ground poles, but the approach to Exercise 3’s second oxer, where riders had to really work to keep the tempo, encourage the horses to move around the inside leg and not allow them to slow down through the turn on the approach.

Exercise 5: Triple Oxers

Set up: Three oxers in a line, 21 feet (one stride) apart

Lastly, Kent had riders jump the exercises in the same order—Exercise 2 off either lead, then the oxer closest to the center of the ring in Exercise 3, turn left, canter around the outside of Exercise 3 to Exercise 4, then turn right and canter down the long side to roll back to the second oxer in Exercise 3, turn right again and then jump Exercise 5, a line of three oxers spaced 21 feet apart. Riders jumped the first oxer, put in one stride to the second oxer and then put in another stride to the third oxer. Finally, riders turned left to finish over Exercise 2.

Every piece of the gymnastic course should be used to improve the horse, Kent reiterated as riders prepared to put the exercises together. He encouraged the riders to continue to think about what was best for the horses and to use the training exercises with as few jumps as possible to achieve the result.

“Each of you can start how you want,” he called. “Use the whole course however you like to improve your horse for tomorrow, thinking about the horse’s weakness and what you can improve. Use each opportunity that you can to make the horse better, whether he drifts or he needs to open his canter more or he gets hot and needs to slow down. You can break apart the whole exercise any way you like.”

Each round was different as the riders zoned in on their individual horses, taking charge to improve what was difficult for their mounts and uncomfortable for themselves.

This article was originally published in the June 2018 issue of Practical Horseman.