After working with a horse for a while and jumping several courses, I am readily able to determine his weaknesses. Does he tend to get quick, or does he get bored and sloppy, rubbing his jumps? Does he get strong, leaning on the bit, or does he swing his hind end, anticipating the turn after the fence leading to it? Depending on these weaknesses, my “between-show” and “pre-class” training techniques vary.

While every horse is different, they tend to fall into categories, and when you run across tendencies you’ve dealt with in the past, a similar procedure usually works.

Most style problems can be solved with gymnastic exercise of one kind or another. The following have been most expeditious in correcting the most common faults I’ve encountered.

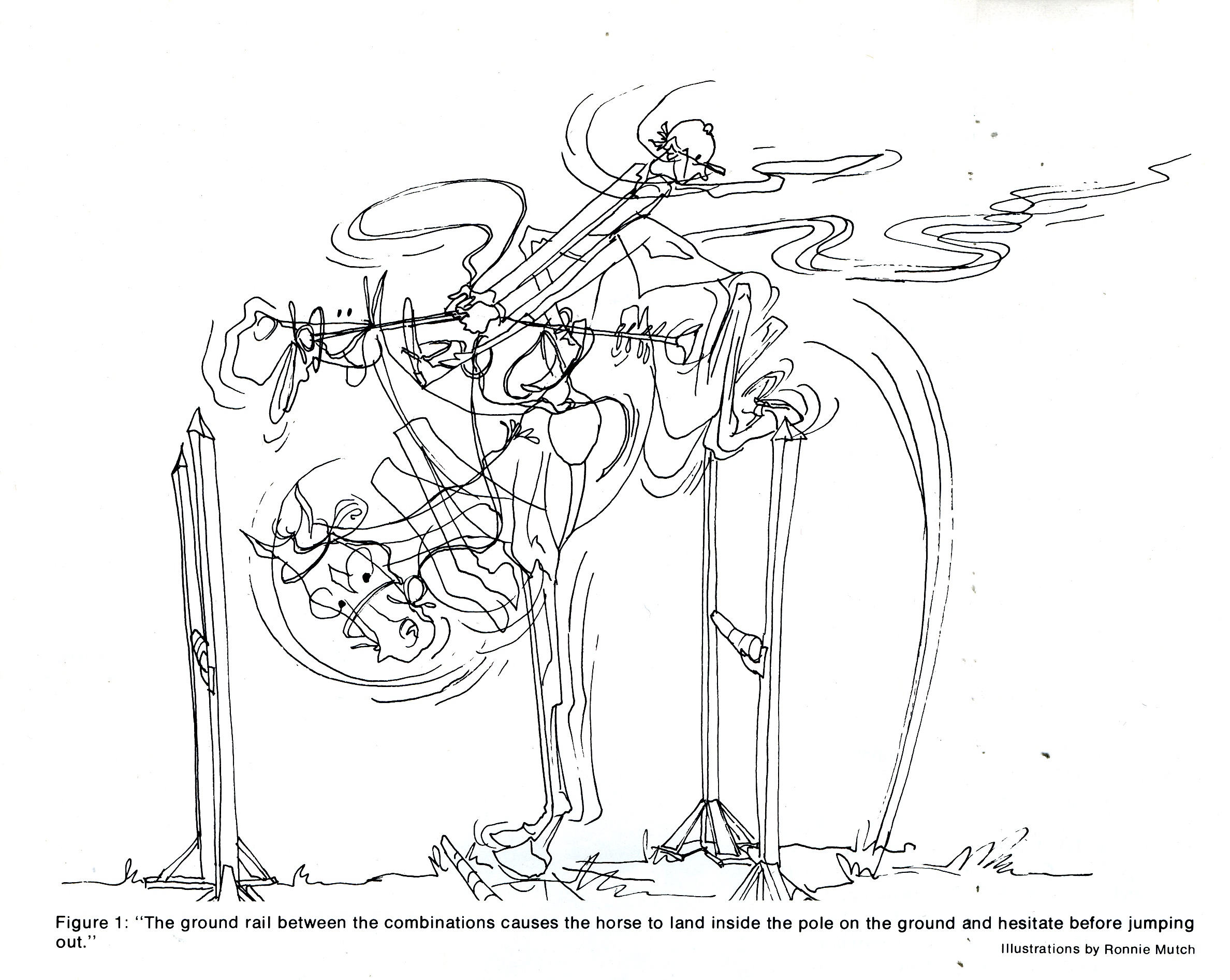

A horse who gets quick to his combinations or tends to overjump, placing his arc too far on the other side, is best schooled through combinations 18 to 21 feet with a rail laid halfway between the two, causing him to land inside the pole on the ground and hesitate before jumping out (see Figure 1, below). The same can be done with a single fence with a rail on the ground on the landing side far enough away so as not to create an attempt to jump it as a spread.

I usually train the horse to be responsive to voice aids in all situations. A sharp “whoa” when halting can be modified to a quiet “ho” in the middle of a combination for this type of quicker individual. In the class, a practically inaudible “ho” often suffices.

A horse who seeks the corner of his fences is usually one who, instead of shortening his stride to arrive at the ideal takeoff spot, moves over to use up the distance. For this problem, I lay poles on the takeoff and landing sides of the combinations perpendicular to the fences on whichever side the horse seeks. If the horse is seeking the right, then I have the rider place his right hand well up on the crest and lead gently out and forward with his left hand, placing more weight in his left stirrup while looking to a point beyond and to the left of the combination. The rider must be careful not to interfere with the horse’s concentration on the rails on the ground by pulling in the opposite direction.

Eye discipline is extremely important. Your eyes control your head, the heaviest and the most influential part of the upper body, and, therefore, control the equilibrium of your upper body over your base of support. Your weight and, subtly, your hands, follow your eyes, and the horse invariably follows the combinations of them all.

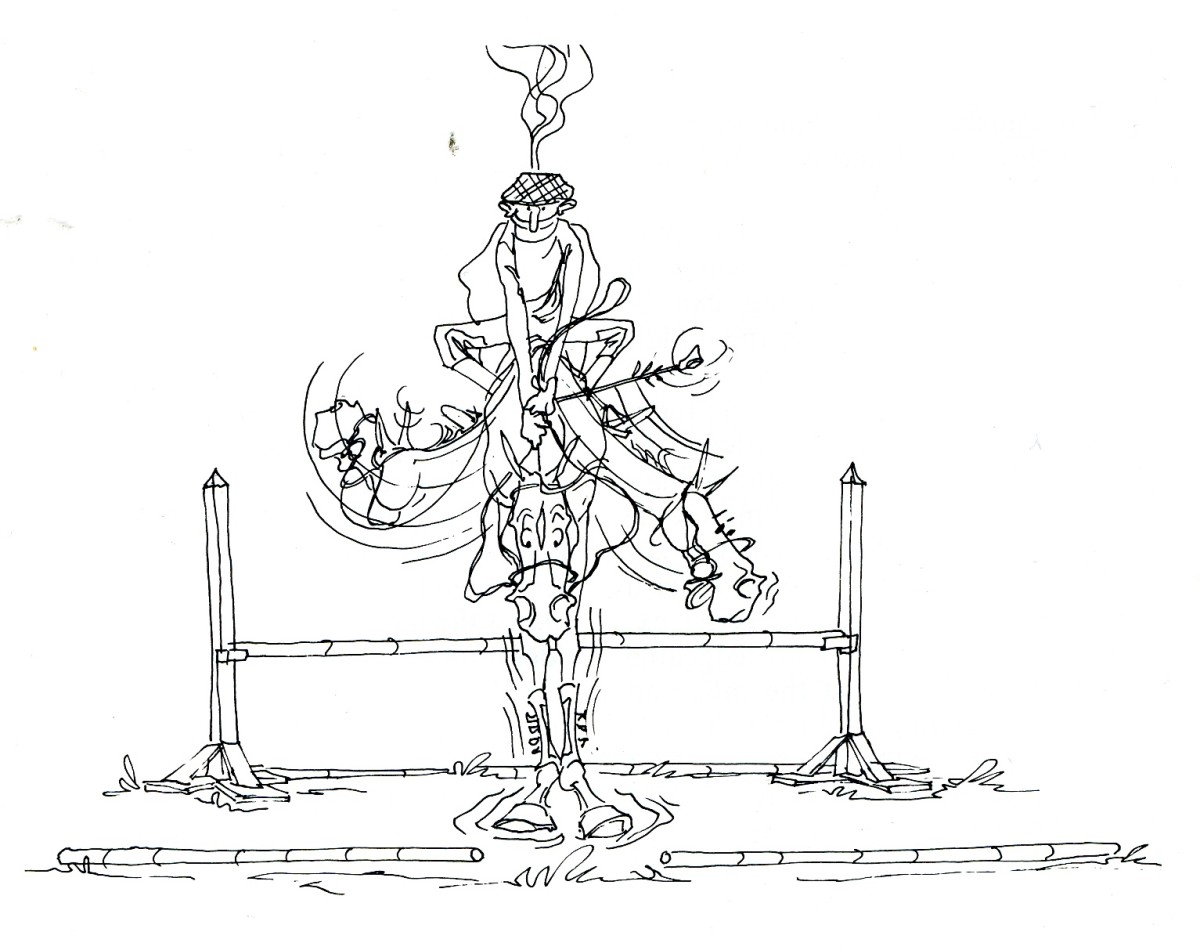

Horses who tend to swing their hind or front end (twisting) are easily corrected with very narrow crossrails. Walking and trotting very slowly to these encourages the horse to wait and jump through the center, thereby using his back, knees and shoulders. I prefer placing the ends of the crossrails at around 6 feet with the center ending up around 2-foot-6. Another successful method of teaching a horse to seek the center is to place two poles on the landing side parallel to the jump, leaving a space in between, again asking the horse to find the center (see Figure 2, below).

For a horse who tends to get flat, particularly jumpers, I trot to a lot of very large verticals. Barely trotting forces the horse to jump around this fence. I often place a pole on the ground about 9 feet in front of the fence—a trot rail—much the same as the last pole of a trotting cavalletti preceding the jump.

To sharpen a dull front end, a vertical to a square oxer within a tight 15- to 17-foot combination can be jumped from both directions with no help from the rider. This exercise really backs a horse up and makes him fast and sharp with his knees. If a horse finds it too difficult (especially as the fences get higher), I lengthen it again to regain his confidence.

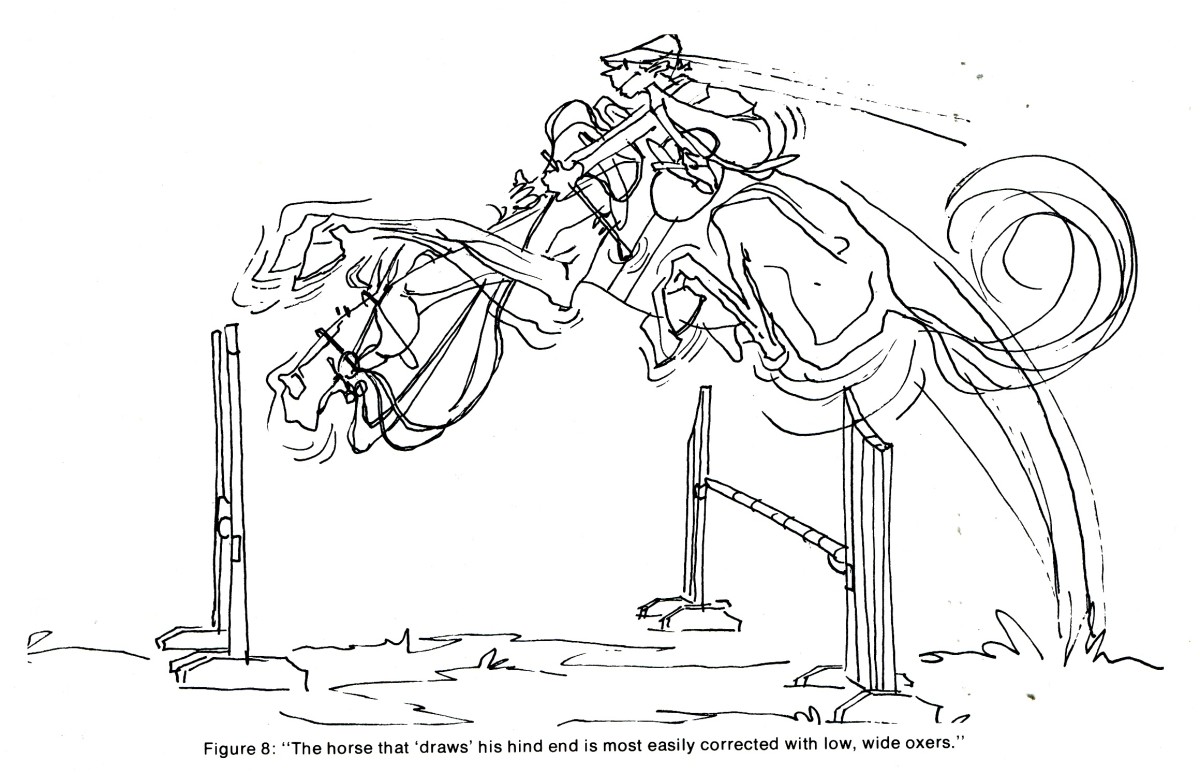

The horse who “draws” his hind end is most easily corrected with low, wide oxers set either singly (see Figure 8, below), sometimes from the trot, or as the out of a combination. Here I use a cantering crossrail, 21 to 24 feet to the oxer, depending on the horse. He may land on the far rail, but soon he learns to flip rather than draw his hind end.

Pre-class schooling depends entirely on either the horse’s last class performance or his inherent weaknesses. I never jump very high with hunters prior to a class. I concentrate on their form and attitude. Depending on the schooling facilities, I may jump a modified version of one of the corrective exercises described in this article that relates to my horse’s tendencies and leaves him with that as his last thought before his round and hope it lasts for eight jumps. I may not jump some horses—particularly those with attitude problems—at all, but will sit on them for 15 or 20 minutes, then just walk onto the course and surprise them with the first jump.

My standby pre-class jump is a vertical beginning at 3 foot with poles laid on the ground on either side approximately where I wish the horse to leave the ground and can control his arc or bascule. I will raise the vertical and adjust the ground rails depending on the horse’s reactions. The pole on the landing side keeps the horse in the air longer and discourages him from cutting down or unfolding too soon in an attempt to return to the ground too quickly.

Spooky horses or those who tend to dwell over strange or spread jumps, I will ask to jump several schooling jumps with either a cooler or rain sheet over the [front] rail and will give them a cluck combined with a stick behind the saddle as their last preparatory recollection. In the ring, a quiet cluck usually carries over.

Sensitivity to each horse’s peculiarities and a reservoir of solutions is probably the successful trainer’s most valuable asset. Common sense and figuring out what the most natural answer is whenever problems crop up will always be the best way. Gimmicks, bits, etc., etc., are merely expedients and may solve a problem for the time being, but the more classical the approach, the more successful and lasting the results will be.

According to Ronnie, Raymond Burr and Bobby Burke, for whom he catch-rode, were chiefly responsible for his riding style while the years he spent with Dave Kelley were the most influential to him as a trainer and horseman.

Ronnie attended the University of Virginia, where he rode and trained horses for the Hunt Meets, helped form its polo team and was a member of its first intercollegiate squad. After studying at the Parsons School of Design in New York City, he spent 12 years in the advertising business in New York as both a creative director and later a partner in his own firm. During this time, he also rode several jumpers as well as a hunter to the AHSA Working Hunter title.

In 1966, he began to ease out of Madison Avenue, and by 1970 he was devoting his full time to horses. Since then he produced four Horses of the Year and trained Fred Bauer to the 1969 Medal championship and the 1970 Maclay championship and Anna Jane White to the 1971 Maclay championship.

He operated Nimrod Farm in Weston, Connecticut, a combination show stable and a school where 300 students a week were taught and 16 horse shows were held annually.

In 1978, 28 years after Ronnie won the Medal Finals, his son, Bert, won the same championship. In 1983, Ronnie became the creative director for Miller’s Harness Company, where he was responsible for the design of advertising campaigns and catalogs. He also remained active in the horse world as a trainer and judge. He passed away in 1999 at age 63.

Since 1999, the R.W. Mutch Educational Foundation has sponsored the R.W. Mutch Equitation Classic. The Classic, held at both the HITS Thermal and HITS Ocala show series in March, is a two-round class—a gymnastic-type course and a more traditional Medal-type course. During the competition, trainers cannot accompany the riders during the course walk or coach them during the schooling session or performance. In addition to being judged in the ring, riders receive scores from judges in the schooling area based on how they warm up and prepare their horses. The class is open to Junior riders who have won at least one equitation class at any of the major winter circuits.

This article with top trainer R.W. “Ronnie” Mutch first appeared in the April 1975 issue of Practical Horseman and offers several solutions to training issues still common today. It also includes Ronnie’s humorous cartoons that illustrate the gymnastic exercises.

In addition to winning the AHSA National Hunter Seat Medal Finals when he was 15 years old, Ronnie trained several riders to Medal Final and ASPCA Maclay National Championship wins, including his son, Bert, who won the Medal Finals in 1978. In addition, Ronnie’s cartoons about horses and riding were published in a book, Mutch About Horses, in 2001. The R.W. Mutch Foundation oversees the R.W. Mutch Equitation Classic and the R.W. Mutch Annual Scholarship.

About Ronnie Mutch

Ronnie Mutch, a leading teacher, trainer, judge and illustrator of many books on horses and riding, began his riding career like many others, including George Morris, Victor Hugo-Vidal and Patty Heuckeroth, at the Ox Ridge Hunt Club in Darien, Connecticut, under the guidance of Otto Heuckeroth and Felicia Townsend. During his Junior career, he was a student of Gordon Wright, Teddy Gussenhoven and Al Homewood, who coached him to the AHSA [now the U.S. Equestrian Federation] National Hunter Seat Medal Final at age 15. He was also reserve champion in the ASPCA Maclay National Championship several times. At 18, he was named to the U.S. Equestrian Team.